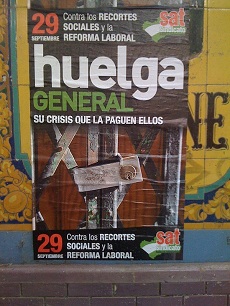

MADRID | The general strike announced for March 29 will be the ninth in Spain’s modern democracy, the 12th if we start counting from the day dictator Francisco Franco died. The general strike is part of unions’ mythology, meaning a show of extra impact and a demonstration of power. There were revolutionary general strikes in 1917 and 1934, even in July 1936 after the coup d’état that was later called Alzamiento, Cruzada (uprising, crusade) and other names full of symbolism. But all that is detestable, too prehistoric for the 21st Century.

MADRID | The general strike announced for March 29 will be the ninth in Spain’s modern democracy, the 12th if we start counting from the day dictator Francisco Franco died. The general strike is part of unions’ mythology, meaning a show of extra impact and a demonstration of power. There were revolutionary general strikes in 1917 and 1934, even in July 1936 after the coup d’état that was later called Alzamiento, Cruzada (uprising, crusade) and other names full of symbolism. But all that is detestable, too prehistoric for the 21st Century.

Today, using our right to go on a general strike (this could be arguably constitutional) sounds like a much watered down gesture. In fact, Spanish trade unions are not making too much noise about it, they’d want it to end without unexpected consequences. They know that the government will not change its position an inch: the labour reform bill pending in Parliament will remain exactly as the government put it. Eventually, unions could even lose some of their influence. If somebody loses control in a demonstration, those who favour reducing the strike right will have the upper hand.

Spain’s government was aware of this strike and probably thinks the sooner it comes the better. President Mariano Rajoy’s cabinet would show an image of authority and diligence in its reformist zeal that will be welcomed in Brussels. The general strike can be useful to justify the need for reform, indeed. Rajoy seems philosophical and not quite impressed. Neither former Socialist president Rodríguez Zapatero was (even if he dreamed of finishing his presidency without a strike). The general strike powder is wet. Amazingly, unions appear unable to bring in other forms of pressure in the new century.

Spain’s president earlier during the Transition process towards democracy, Adolfo Suarez, endured two attempts of a low-key-strike with little success because of the soaring unemployment rate: the first one was local (1976); the second called by European unions (1978). There was a third attempt after the failed 23 February military coup, but it ended up being merely rhetorical.

Our first Socialist president, Felipe Gonzalez, suffered three general strikes with uneven results and consequences. The first one was in 1985 against a reform of the pension system. The strikers did not get anything and the reform proved to be crucial. Unions showed their power against a leftist government that paid less attention to them than they had wished.

The second strike, in December 1988, was the dream strike. That day nothing moved, the TV sets went black at midnight and millions of Spaniards decided to take the day off. It was the strike that knocked out the government and put the president on the brink of resignation. Citizens were protesting against a labour reform that among other measures introduced Germany’s internship contract. It would have been useful for youngsters today. That strike showed the union power and pushed the government towards public spending, which proved to be a wrong measure, but at that time helped the president to win the election with an absolute majority.

Unions attempted two other general strikes against the governments of Felipe Gonzalez in 1992 and 1994, who had learnt already how to deal with them. Those strikes had limited support, although the government avoided confrontation as it had no interest in weakening the unions that were part of the establishment.

Year 2002, the strike against Conservative president José María Aznar’s labour reform (with absolute majority) had a moderate support. The government acted with concern and clumsiness. Although unions did not achieve their goals and the reform continued, the government paid a price for it and some ministers were replaced. Aznar was tough. However, that time his legs trembled.

The strike against Zapatero in 2010 passed almost unnoticed. The government did not take any action, avoiding to upset the unions. The opposition was not belligerent either: they knew it would weaken the government. After that day, everyone turned the page. Not measures were taken.

The use of a general strike as a political tool is soon to become a memory of the past. But since unions don’t have further resources, they have to return to traditional recipes in order to reclaim a role in the public scene.

Be the first to comment on "General strike for the umpteenth time in Spain: a worn out threat"