By Luis Arroyo, in Madrid | The great cause of the financial crisis was the spreading of risk through previously unknown channels. New financial instruments were invented, ‘collateralized’ with original assets and loans (mortgages), and sold and resold to re-lend the proceeds of the sale. The standardization of the process, despite its darkness, made it easier to hide the risk to the rest of the world. The initial risk was split and sold as well as limited and valued.

A CDO contained slices of mortgages of different quality; it was like putting money over paper from newspaper cuts and just looking at the money that was sold to an investment fund, let’s say, in a remote city in Sweden.

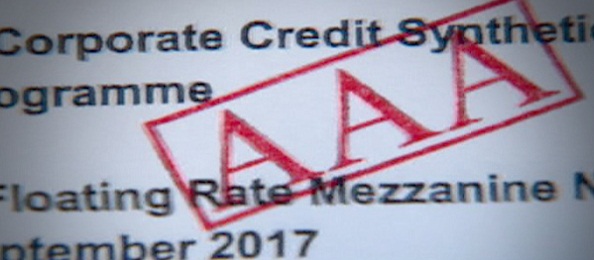

It was as if risk had disappeared. The risk of lending money to somebody of low and uncertain income, 130% of the value of the person’s purchase, became something measurable and profitable. The transmission chain soon got larger and products looked so far from the initial risk that seemed less influenced by it. However, the problem is not individual but systemic risk, which is impossible to see when millions of sub-products from other products have been stretching the string, and leverage not being noticeable at first glance: all assets look AAA, although their content is dubious since the stretching process is made by mixing different levels of risk.

This caused thousands of silent bombs placed in global banking assets. Should one of them explode, all other would do so in a perfectly synchronized time.

The reason of collapse was trivial: the cooling and subsequent housing bust, the mainstay of the artificial pyramid. First, the Fed raised the interest rate to 5.25% from the 1% where it had rested for a year. That reduced the demand for flats, of course. Home prices fall increased mortgage defaults, which were the basis of these products spread throughout the world. Then, Paribas was the child in the story ‘The Emperor has no clothes’, announcing that they were suspending the customers’ demand for return of their funds because they were incapable of knowing the value of such securities deposited in such funds. As soon as someone says the emperor has no clothes, everyone sees that he is naked. Then everyone runs to sell and they want cash. Everyone.

By all this I mean that first there was the financial crisis, then the monetary one. Later came the recession, despite what my friends Marcus, Scott, Cristian say. Because the signs of falling real estate prices and unrest in the interbank markets were remarkably pre-slowdown of GDP and much earlier than the recession. The housing price fall began in 2006, that of CDO, in 2007, and the recession didn’t show up until well into 2008. Therefore it is plausible to think that first was the financial hen that stopped laying gold eggs. And that is why I am not buying my friend’s theory that if the Fed had maintained its PIBN nothing would have happened.

Luis Arroyo is a former Bank of Spain economist. He writes for www.consensodelmercado.com.

Be the first to comment on "The crisis, the chicken and the egg"