By CaixaBank research team, in Barcelona | With half of 2012 already gone, three issues continue to be fundamental in order to strike some sort of balance in the situation for emerging Europe: the intensity of the financial contagion entailed by the debt crisis, Hungary’s situation and the extent of the slowdown in activity.

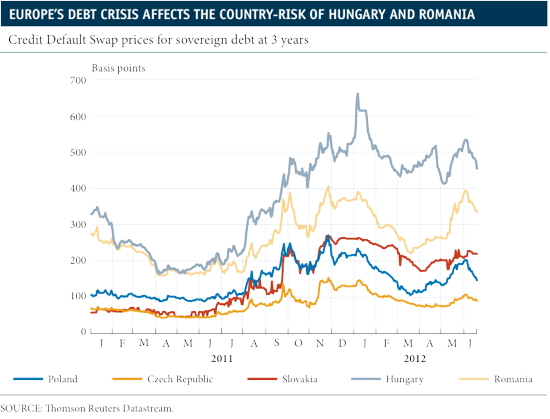

Starting with the first of these issues, the trend in risk premia, measured by the value of credit default swaps for three-year sovereign bonds, indicates that the high financial stress caused by the combination of doubts regarding the Greek elections and the uncertainty regarding the situation of Spain and Italy (therefore between the beginning of May and now) has been more appreciable in the case of Hungary and Romania and more moderate in the case of Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The situation of these last three countries reflects minimal concern in terms of public sector solvency and few direct links (commercial or financial) with Greece. Romania contrasts precisely in this last aspect as the notable importance of Greek banks in its national banking market and close commercial ties are being reflected negatively in the country’s risk premium.

The case of Hungary is more complex. As is already known, because of relatively high external financing needs for 2012 (albeit far from any immediate inability to meet these needs), last November the government asked the European Union and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for financial assistance. Moreover, in the longer term, the financial markets were concerned about one of the highest public debt situations in the region (in the order of 80% of GDP).

After requesting multilateral financing, negotiations broke down when, at the end of 2011, the government took everyone by surprise and adopted a new regulation restricting the independence of Hungary’s central bank. There were also signs that the budget was not being adjusted so that the European institutions, via an excessive deficit procedure, decided to withdraw part of the cohesion fund as from 1 January 2013.

After months without details being given out, over the last few weeks two relevant events have occurred that could pave the way towards financial aid. Firstly, conversations between the central bank and the government have given rise to an amendment of the legislation that will be sent to the Hungarian parliament by early July at the latest. This legislation restores key powers to the central bank regarding monetary policy. Without waiting for this new regulation to be completely adopted, the government will immediately ask the IMF and European institutions for formal negotiations to be restarted.

The second relevant change is the announcement of a series of budget measures for 2012 and 2013 that the Commission believes are adequate to ensure public deficit falls to a level lower than 3% of GDP. As a consequence, it has recommended that the excessive deficit procedure be suspended and the fine not be applied. All this explains the prevalent perception among financial investors, namely that, by the end of the summer, Hungary will have received international financial assistance.

According to this interpretation, it is logical why, from mid-March (when the financial markets ruled out the possibility of negotiations starting up again) and up to 7 May, the Hungarian risk premium fell by almost 100 basis points. Unfortunately, on this date the result of the first Greek elections was announced, starting a period of strong risk aversion. Within this context, the trend in the risk premium indicates that investors include Hungary in the group of weak EU economies. This is due not only to the country’s fiscal situation but also to expectations of a double dip recession.

This last factor leads us to the third issue we mentioned at the beginning of this section. Given the notably uncertain macroeconomic scenario in the euro area, and with business indicators in the Union’s main economies clearly deteriorating, the issue of determining the extent of the slowdown in activity in emerging Europe has become particularly difficult. It should be noted that the growth figures for the first quarter place Romania and the Czech Republic in recession (understood as two consecutive quarters with GDP in decline) and Hungary practically in this situation. Only Poland and Slovakia manage to escape this weak scenario.

The latest activity indicators suggest that the second quarter is unlikely to improve on the first three months of the year. The most inclusive indicator of all, namely that of economic sentiment, worsened in April and May in all the countries we cover here, with the exception of Romania, which posted a moderate improvement. Deterioration is greatest in the case of Hungary and the Czech Republic. All this suggests that, in the second quarter, the Czech Republic will continue in recession while Hungary will enter into the same situation. Romania could be coming out of recession in this second quarter, while Poland and Slovakia will grow in quarter-on-quarter terms but at a low rate. From now on, a gradual improvement should be expected (certainly slow) in all these countries, with the probable exception of Hungary, which should fully experience the effects of its fiscal adjustment underway during the second half of 2012.

Be the first to comment on "Emerging Europe: euro contagion, Hungary and economic slowdown"