1. Greater consumer-privacy protections

In recent years, billions of consumers have come to enjoy – and even rely on – the “free” digital services that companies like Facebook and Google provide. Yet recent scandals over privacy are causing a growing number of people to realize what Apple CEO Tim Cook once said best: “when an online service is free, you’re not the customer… you’re the product”.

To be fair, Neil Dwane points that not all users want to opt out of the ads and services that FANG-type firms sell.

In fact, some simply don’t care how their digital information is used, which could raise the risk of cyber-crime and reinforce the need to manage personal data more carefully. Others may be concerned about what happens to their personal information online, yet may be unable or unwilling to pay for a service like Facebook’s should it change its advertising-supported business model.

As the fight continues over the monetization of private information, the European Union will soon step into the ring with its new General Data Protection Regulation – a robust set of requirements aimed at guarding the personal information of all EU citizens. Launching in May 2018, GDPR will raise the costs of mining and disseminating digital data, which could affect the bottom line of any firm doing business in the EU. That includes the FANGs.

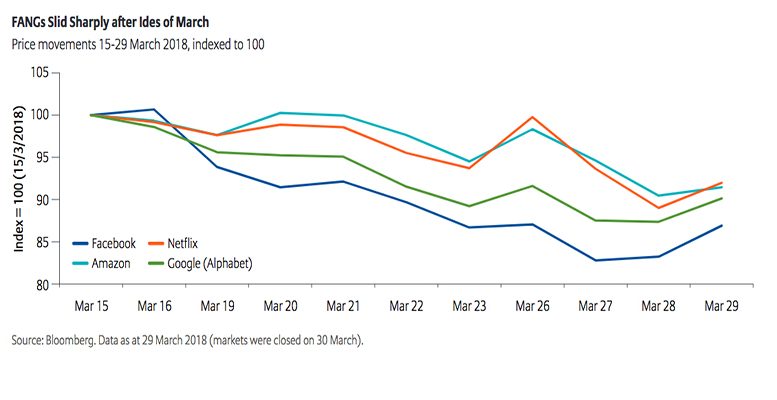

With privacy concerns increasingly making headlines, Global Strategist at Allianz Global Investors expect more jurisdictions to put an emphasis on personal privacy instead of taking a laissez-faire approach. If this movement spreads to society at large, perhaps the social propriety of social media could be called into question. Even if the #deletefacebook movement ultimately loses steam, the customer is always right – and votes with his or her feet.

2. Calls for better corporate governance

Before recent revelations about alleged election interference, much of the wariness about social media was limited to non- millennial generations. But today, consumer angst seems tangible and rising, and attention is turning to the corporate-governance structures – or lack thereof – that permitted what many consider to be the systematic abuse of society’s data and trust. Arguably, the governance of some of the FANGs and their brethren has rested with young billionaires and boards with little real-world expertise, let alone a desire to exercise restraint. In opinion’s of strategist Dwane:

One clear result has been their weak management of the mounting crises, which seems likely to alienate both users and advertisers in a self-reinforcing fashion. Moreover, one key avenue of recourse – pressure from shareholders – could be less than effective on FANG firms due to the dual-class share structure that gives their founders outsize control.

3. A changing investment environment

During the pronounced equity market run-up of recent years, some FANGs offered rising earnings to go with their soaring share prices – a factor that was generally absent during the dot-com days. Yet the business models of many of today’s Big Tech giants may rely less on profitability than on access to cheap credit – an unintended consequence of the extremely accommodative monetary policies set by central banks in recent years. With higher rates on the horizon, easy money will be harder to get. “ This raises a key question”, says Dwane:

If the rising cost of capital imperils tech firms that are actually running at a loss, can the disrupters continue to disrupt? Could we see some of the world’s largest corporations – some less than 20 years old – fall to Darwinian forces as they fail to adapt?.

4. A backlash against monopolist models

Governments have been known to help give birth to monopolies they then spend decades trying to control – and the FANGs and their ilk may find themselves on the receiving end of similar efforts. Politicians and regulators know that economies need a regular supply of efficient competition to promote innovation and productivity, but that supply is stifled by the “winner-take-all” effect at work today. Adding to the monopoly accusations plaguing Google, Amazon has a model that is equally problematic for its competitors. Going head- to-head against such a company – which offers consumers a single marketplace with renowned services and efficiencies – becomes all but impossible when it is under little pressure to make a profit, which is normally what a free-market economy would demand.