Atul Singh via Fair Observer | The Belt and Road Initiative is China’s bold and risky response to internal tensions and external pressure, but it is not backed by an inspiring idea.

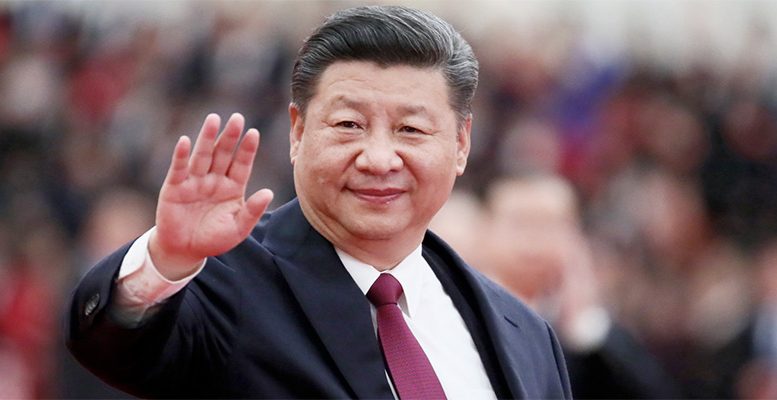

President Xi Jinping, the modern-day emperor of China, clearly has a deep sense of history. On September 8, 2013, he gave a speech at Nazarbayev University in Almaty at the invitation of Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev. Xi quoted a Chinese saying — “[A] near neighbor is better than a distant relative” — and referred to Chinese envoy Zhang Qian.

Apparently, this legendary envoy of the Han dynasty came to Central Asia 2,100 years ago. In the words of Xi, Zhang’s “mission of peace and friendship” led to the “ancient Silk Road linking east and west, Asia and Europe.” Xi reminded the audience that his home province of Shaanxi was the starting point for this legendary trade route and Almaty was on it too. And he called for a modern reincarnation of the ancient Silk Road.

In what will go down as a historic speech, Xi promised to create an “economic belt along the Silk Road” that would benefit “the people of all countries along the route.” Thus was born the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Its five prongs included increased policy communication, improved connectivity across Asia, unimpeded trade, enhanced monetary circulation and better understanding among people of different countries.

Less than a month later, Xi gave another speech in Indonesia. Again, he invoked old ties going back to the Han dynasty. Importantly, he also invoked the 15th-century Chinese admiral Zheng He. This sailor from the era of the Ming dynasty made seven voyages and visited many key islands of Indonesia.

Replete with references to literature and shared memories of independence struggles, Xi quoted another of those proverbs for which his country is rightly famous: “[A] bosom friend afar brings a distant land near.” In a land still scarred by the shock therapy that the International Monetary Fund inflicted upon the country in 1997, Xi emphatically rejected the “one-size-fits-all development model,” reassuringly promising to respect the path Indonesia takes for its economy, politics and society. Instead of inflicting policy prescriptions like the IMF, President Xi promised China would “share opportunities for economic and social development with ASEAN, Asia and the world.”

What Is the BRI?

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) calls the BRI “the most ambitious infrastructure investment effort in history.” This effort involves “creating a vast network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, and streamlined border crossings, both westward—through the mountainous former Soviet republics—and southward, to Pakistan, India, and the rest of Southeast Asia.”

ChinaPower, an effort by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) to unpack the complexity of China’s rise, captures the stupendous figures involved. About 4.4 billion people live in countries that have signed up for the BRI. They comprise 62% of the world population. The GDP of these countries is $23 trillion. Trade between BRI countries and China amounted to $3 trillion between 2014 and 2016. In the first half of this year, as per Bloomberg, “Beijing signed about $64 billion in new, mostly construction contracts, a jump of 33% from 2018.” What is this construction spree all about?

To understand China’s construction frenzy, it is important to remember that there are two prongs to BRI. One is rooted in China’s outreach to Central Asia. It aims to bring about a renaissance of the ancient Silk Route. The other is to build upon Zheng’s maritime voyages and create a network of ports that link China to the rest of the world. Asia and Africa are to be a particular focus. In addition to physical infrastructure, the Middle Kingdom will create 50 special economic zones à la Shenzhen, the first such zone established in 1980 as a result of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms of 1978.

Although a chemical engineer by training, Xi is a keen student of history. He remembers a time when China was the world’s largest economy in the world. Chinese silk, spices, jade, porcelain and other goods went West, while gold, silver, ivory, glass and various items came East. According to many analysts, the BRI seeks to create the infrastructure and system of trade that makes China top dog again.

Emulating their American counterparts, the Chinese speak of the BRI as benefiting everyone involved. If one is to believe Wang Yiwei of Renmin University, the Middle Kingdom seeks to “promote lasting peace, common security, common prosperity, openness and inclusiveness, and shared and sustainable development.” He argues that China would share “its development experience, but it will not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries.”

Wang claims the Chinese model “aims to promote a perfect combination between a functioning government and an efficient market, in which the visible and invisible hands both play their roles.” He asserts that ultimately the market would play a decisive role, but countries where the market economy has not developed would have an alternative to the failed free-market model peddled by the IMF, the US and the West.

Even as Wang reassures the world about the Belt and Road Initiative, many shudder in horror at its scale, scope and speed of the project. The CFR worries whether the BRI is “a plan to remake the global balance of power.” Could the BRI be “a Trojan horse for China-led regional development, military expansion, and Beijing-controlled institutions?”

So, what is the real story? Is the Belt and Road Initiative the benign win-win that Wang paints it to be, or is it a sinister plot for world domination by a secretive, authoritarian regime?

The Chinese Rise and the Americans Respond

Since 1978, China has experienced the biggest and fastest transformation in history. Its economy has grown exponentially. Deng’s experimentation with reforms has paid off handsomely. With its vast supply of labor, entrepreneurial energy and national ambition, China has come back with a bang on the world stage after two centuries in the shadows.

China’s economic rise is based on mass industrialization. Data from the World Bank tells us that exports went up from a mere 4.5% of GDP in 1978 to 36% in 1996. Since the glory days of 2006, Chinese exports have fallen to 19.5% of GDP as per 2018 figures, but even this diminished percentage tells us that much of the production of China’s factories is still shipped overseas. This export-led model has served the country well and, for the last few years, it has become the workshop of the world. This workshop has supplied the planet’s biggest market: the US. Access to this market has been critical to China’s rise.

So, why was the US happy to import from China? Part of the answer lies in the Cold War with the Soviet Union. American imports fueled the rise of South Korea, Taiwan and Japan after World War II. The free-trade order that Uncle Sam created locked its allies firmly into its own orbit. Countries that stayed out of the American solar system such as India, Vietnam and China remained poor.

When China took to reforms in 1978, the US was itching to wean the Middle Kingdom away from the Soviet Union’s bosom. In 1991, when the dysfunctional regime in Moscow completely collapsed, the US still saw benefits in incorporating China into its orbit. Uncle Sam was even willing to overlook the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests because its high priests bet that economic transformation would lead to political change in China’s timeworn land. Eventually, prosperity would make the Middle Kingdom more open, plural and democratic.

Thanks to this assumption, the US supported China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. There was another reason for getting the Chinese into the WTO. Importing from the Middle Kingdom improved Walmart’s bottom line because Chinese goods were inevitably cheaper. After all, wages in this country of over a billion were less than in the US. Not only shareholders of Walmart but also American consumers were happy. After all, who does not want to buy more for less?

Not everyone won because of this arrangement. Many American workers lost their jobs when production moved to China or Mexico. The wise men in charge of the US economy told them that their pain was short term. Broad, uplit sunlands were just around the corner. Oracles like Bob Rubin and Larry Summers proclaimed that a more integrated world economy with freer movement of capital would lead to cheaper products, better paid jobs and a cleaner environment. In 1991, when Summers was at the World Bank, he proposed that many poorer countries were under polluted and toxic industries could move there from the first world.

When this memo was leaked in 1992, it caused a minor furor but most Americans bought into the gospel of trade. Even then there were some curmudgeons like Ross Perot, the populist 1992 presidential candidate. He inconveniently warned that wages would decline because of overseas competition. Even then, Americans were worried about fair and unfair competition. Perot saw “one-way trade deals” leading to a “giant sucking sound” of jobs going south. Unsurprisingly, this Texan billionaire’s warning was pooh-poohed away by economists at places like Harvard, Yale and Chicago. Even as Perot made his comment in the pre-election debate, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton proclaimed that trade was a win-win and smiled on.

Economists, the new temple priests of globalization, also said trade was a win-win. Clinton bought into this prophecy with the zeal of a new convert. In 1994, this Arkansas boy claimed trade would allow “all to reap the benefits of enhanced specialization, lower costs, greater choice, and an improved international climate for investment and innovation.” If greed was good in the era of Ronald Reagan, globalization was glorious in the age of Clinton.

In 2001, China’s entry into the WTO gave it an autobahn with no speed limit to zoom ahead. As the US got embroiled in Iraq, the Middle Kingdom dutifully followed Deng’s maxim: “[H]ide your strength, bide your time.” It industrialized much as the US did in the 19th century, by stealing industrial secrets, protecting key sectors and providing manufacturing with steroids such as massive infrastructure spending and cheap credit.

Eventually, China’s growth started making Americans nervous. Some started to worry about rising US current account deficits. Inevitably, the top dog was bound to push back and it duly did. After years of negotiations, Barack Obama signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2016, shutting out China from a gargantuan trade deal. Through the TPP, the US sought to seduce the Asian giant’s troubled neighbors away from its sinewy arms. This trade deal was a part of the Obama doctrine, which envisaged the US pivoting to Asia from the Middle East. Naturally, it caused China much concern.

If Obama chose jujitsu, President Donald Trump has opted for a bar fight. As this author observed in 2018, Trump has declared economic war on China. Under his administration, the mood in Washington has turned sharply against the Middle Kingdom. Thomas Friedman, the celebrity columnist of The New York Times, has declared that China deserves Trump. Now, China is no longer just making “toys, T-shirts, tennis shoes, machine tools and solar panels.” It is competing with the US in “supercomputing, [artificial intelligence], new materials, 3-D printing, facial-recognition software, robotics, electric cars, autonomous vehicles, 5G wireless and advanced microchips.”

In brief, Friedman agrees with Trump that China is now a rival. Its “subsidies, protectionism, cheating on trade rules, forced technology transfers and stealing of intellectual property since the 1970s [have become] a much greater threat.” In the old days, Friedman argues it did not matter if the Chinese were “Communists, Maoists, socialists — or cheats” but, now that it is a competitor, “values matter, differences in values matters, a modicum of trust matters and the rule of law matters.” Tellingly, a Democrat trumpeter is giving a clarion call for a new Cold War unleashed by a much-despised Republican president. To modify the words of a Nobel laureate, the times indeed are a-changin’.

Chinese Counter Response

Even as the US has struck to chop down the Chinese tall poppy, the Middle Kingdom has played its own set of cards. To counter Obama’s China containment policy, Xi did two big things. First, he launched Belt and Road Initiative in 2013. Second, his administration formulated a new “Made in China 2025” industrial policy in 2015. Seeking to avoid the middle-income trap and just make toys or tennis shoes for Friedman’s grandchildren, the Chinese decided to embrace high-tech manufacturing. Their policy sets out 10 high-tech industries as a national focus, including electric cars, advanced robotics and artificial intelligence.

In an earlier article, this author pointed out how high-tech manufacturing in brainbelts was putting the US and Europe back on the map. China seems to be aware of this trend. Hence, it is making sure that it does not get stuck in low value-added, low wage manufacturing. China has set targets, is providing subsidies and making foreign acquisitions to close the gap with the West. Its government has also forced foreign companies operating in China to share their intellectual property and intellectual know-how. Tellingly, intellectual and industrial espionage remains part of the Middle Kingdom’s modernization toolkit.

The Middle Kingdom still has a long way to go. People often forget that China’s per capita annual income is still a measly $8,000, much below the US figure of $56,000. China may have grown dramatically in the last four decades, but it is still markedly poorer than the US. And for years, this poor country has lent the rich one money. Over the years, China has accumulated huge dollar reserves. In part, it has done so to depress its currency, keep exports cheap and its factories humming. Yet this imbalance was never sustainable.

A few months before the financial crisis of 2007-08, this author argued that Americans could not keep consuming on Chinese debt. The “Yankee Doodle and Dragon Dance” had to end. That end is nigh for three reasons. First, American sanctions have dampened demand for Chinese goods. Second, high-tech smart manufacturing is making supply lines shorter and bringing back factories to the US. Third, an energy revolution has quietly transformed the US. It is the largest natural gas producer in the world with prices staying below $3.00 per million British thermal unit (Btu) since 2015. Cheap energy costs mean that many energy-intensive industries can move back to America. The savings in labor costs are outweighed by cheap gas.

David Petraeus, a retired general and former spymaster, put this figure into context by pointing out that the price for natural gas for America’s competitors is much higher. In 2014, he observed that the Japanese were paying $16-17, the Chinese $10-12 and the Europeans $9-12 in contrast to the Americans who were then paying around $3.70 to $3.80 per million Btu for natural gas. Since then, prices have declined and the “extraordinary comparative advantage” of the US has only increased. Bit by bit, the US is going to produce more and import less. So, China has no alternative but to try something else.

*Read the entire article here.