The stagnation in productivity is serious, a tragedy. Labour productivity is the result of dividing the product obtained (some of components of GDP) by the number of hours worked. It can also be calculated dividing by the number of employees, although the different kinds of contracts (part-time, construction contracts etc.) create distortions. The more GDP expands, the more productivity increases. And the more employment rises, the less productivity increases. The more productivity there is, the bigger the pie to be shared out between businessmen and workers and then, via taxes, between public investment, social spending and the rest.

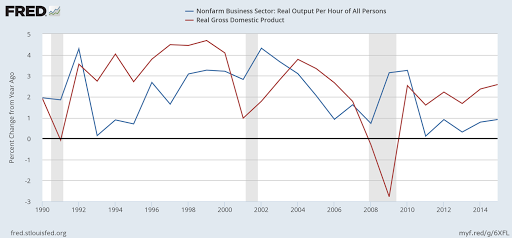

It’s easy to infer that feeble GDP growth is to blame for the current low productivity. In the US, GDP is faltering, growing only very slightly, as can be seen in the red line of the following graphic.

Growing less than 2%, apart from the last figure, while the labour market is storming ahead. Such high employment and such low growth produce very low productivity: growth of less than 1%. The good times are when employment and productivity increase simultaneously, because GDP grows more than employment. As happened between 1992 and 2002, years of huge advancement (if we don’t look at the financial sector).

As can be seen in the second graphic (published by the FT), all the countries represented register an annual increase in productivity of below 1%.

This means that there is a paltry margin for spending on salary increases and business investment. We know that investment has stagnated in all these countries. We also know that the jobs’ recovery has been thanks to new contracts which don’t offer security or high salaries.

That means we now have to grow strongly, before more and more people and companies are decapitalised. But how? The OECD has offered a three-pronged programme: fiscal monetary policy combined with structural reforms. Demand plus an adapted supply.

I believe that the crux of the matter has to do with the rate of growth and investment. Has productivity been another victim of the crisis, or can we see downward trends in the graphics? Do we focus on supply, the European way of doing things, or do we have to fuel demand further, consolidate an upward trend in investment? Up to a certain point, the two approaches are compatible.

But there is one which is unequivocally a priority: growth, confidence, demand. The European strategy has failed: the US strategy has partly worked, with big holes. Either way, a sign that it’s demand which is damaged. A sign that productivity is not a problem of supply, but of growth in demand. More growth fuels more productivity, even with an increase in employment.

*Image: neetalparekh via Foter.com / CC BY