It is a simple story of failure, but one that fits the facts. It´s also based on a simple premise: An inflation obsession that took hold in 1974.

It´s also a story that gives credence to Market Monetarists’ recommendation that central banks should level target NGDP.

It teaches us Abe´s latest move is one that goes in the right direction.

The story is told through 3 charts.

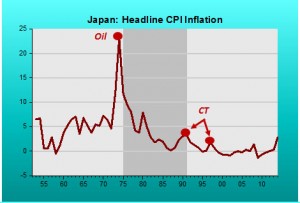

The trigger of the process that defined the Japanese economy was the domestic inflationary impact of the first oil shock. Inflation in 1974 climbed above 20% and worries about inflation and its effects on the real economy, including the worst bout of labor unrest since the war, quickly turned price stability into a priority of economic policy. More than a “priority”, price stability became an “obsession”. This is consistent with the reaction to the introduction of the consumption tax (CT) in 1989 and the CT increase in 1997.

We should put “price stability” in scare quotes too. The Fed and other central banks increasingly seem happy to interpret this as zero inflation is acceptable, but anything over 2% a precursor to hyperinflation at worst and a return to stop-go monetary policy chaos at best.

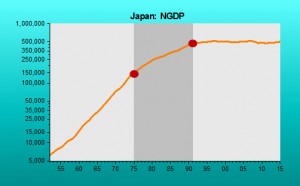

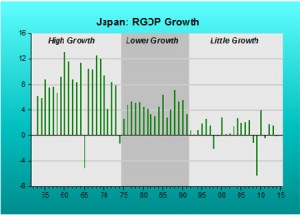

What central bankers should recognize are that labor unrest and consumption taxes are supply shocks and the best the BoJ could have done was keep NGDP on the level path it had been on since the early 50s. The BoJ monomania on price stability led to them wanting to “eradicate” inflation, not keep it in the 0% – 5% range that held in the 20 years before the oil shock. To do that, the BoJ strongly reduced the trend growth of NGDP. Did they think that crushing inflation would somehow teach labor a lesson? Perhaps.

The new trend held until 1990, when the “tax shock” gave a very short term uptick to inflation. Thereafter NGDP trend growth has remained close to zero. Competent central banks should stay loyal to long-term inflation expectations, but seem unable to do so only when headline inflation (even if due to CT increases) is above target. If headline or even core inflation is below target they all too easily fall back on those long term, well-anchored, expectations to justify doing nothing, or worse and tightening.

The BoJ´s goal of price stability (“zero” inflation) was attained, but real growth all but disappeared as monetary strangulation took place.

Abenomics, introduced with the election of Abe in late 2012, has improved things somewhat but it´s still tied the self-defeating inflation target (not “zero” but 2%), and as the recent experience of many developed countries with targets for inflation has shown, you can easily get into a “stagnation trap”!

Japan was the first country to (implicitly) pursue an inflation target. Now it looks on the verge of being the first to pursue an (explicit) NGDP level target. Maybe it will not take as long for present day inflation targeting countries to follow suit.

Who said there´s no irony in economic policy!

PS: The Economist makes exactly that suggestion:

A target for nominal GDP (or the sum of all money earned in an economy each year, before accounting for inflation) is less radical than it sounds. It was a plausible alternative when inflation targets became common in the 1990s. A target for NGDP growth (ie, growth in cash income) copes better with cheap imports, which boost growth, but depress prices, pulling today’s central banks in two directions at once. Nominal income is also more important to debtors’ economic health than either inflation or growth, because debts are fixed in cash terms.