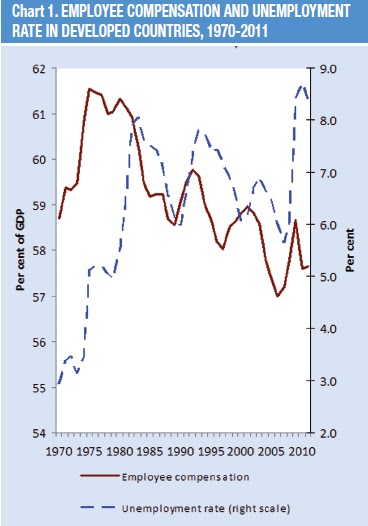

Can you prescribe the same medicine to an economy that grows approaching its full potential, and to one that struggles against depression with no visible trends of crisis exit? Well, you shouldn’t. This chart from Naked Keynesianism tells us why.

According to the theories of the pro-austerity gang, a drop in labour costs is always a good thing to happen because it makes hiring cheaper, which increases employment and cuts unemployment down. That may be true, but only during strong growth periods–as during 1990 to 2000, that is, the longest without recession since the end of World War II, also called the ‘Great Moderation’ because inflation was successfully tamed.

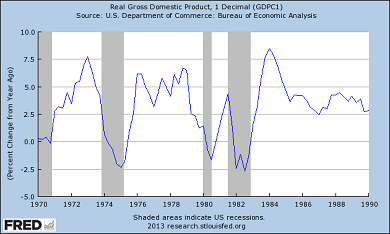

Quite differently, during these crisis years, real wages have fallen while unemployment has risen, too. This combination also appeared during the oil crisis in 1970-1980, we have to admit, but it isn’t a rebuttal of my argument: back then, the increase in commodity prices couldn’t be absorbed by a parallel increase in salaries, and it was a time of low growth instead of negative GDP, as shown here. It was a time of excessive inflation on prices and salaries, not a recession.

Lower salaries do not always bring more employment. This is a myth. The liberalisation of the labour market is altogether another matter, and in some Eurozone countries–as Spain–we are still waiting for it to be implemented. But what we know is that the monetary and financial environment must be appropriate to hold and push demand further.

Tackling only the labour market is not a miracle cure. Structural reforms cannot generate wealth and jobs.

Be the first to comment on "The myth of lower wages and job creation"