Zhu Haibin via Caixin | High savings rates, a longtime hallmark of China’s economy, have helped the country retain its financial stability despite rapid economic growth. But China’s aging population is cutting into savings rates, and the effect on China’s economy and financial sector could prove disastrous.

China’s gross national savings, or GNS, rose from 35 percent of GDP at the beginning of the millennium to about 50 percent in 2011. It has since fallen to 46 percent, the World Bank said. JPMorgan Chase said it expects China’s GNS to drop to 35 percent of GDP by 2020.

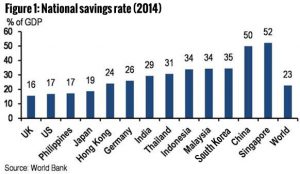

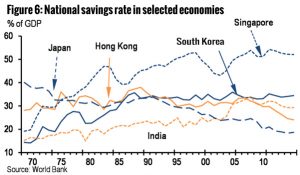

China’s GNS is second only to Singapore among Asia’s emerging markets and far surpasses those of the United States (17 percent) and the United Kingdom (16 percent). (Figure 1).

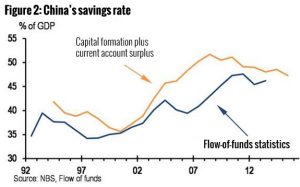

The GNS can be calculated in two ways. The first, “the expenditure approach,” adds capital formation to the current account balance. The second method, “the production approach,” calculates the GNS from flow-of-funds statements. Both approaches show China’s savings rate as among the highest in the world, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) said. (Figure 2).

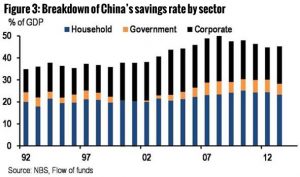

The production approach allows economists to separately analyze household savings, corporate savings and government savings (Figure 3). All three sectors rose quickly in the first decade of this century, and have only recently showed signs of slowing. Household savings rose from 20 percent of GDP to 25 percent, while corporate savings rose from 15 percent to 20 percent, much higher than international averages, the NBS said.

Why are China’s savings rates so high? The following factors account for high savings rates in all three sectors.

1.The proportion of working-age Chinese citizens is rising steadily, contributing to higher household savings rates.

2.Limited access to external financing methods coupled with corporate management issues such as a low propensity to distribute stock dividends explain why companies like to save. Because external financing opportunities are limited, businesses must rely on retained earnings and internal financing to stay afloat.

3.The economic reforms of the 1990s did away with the lifelong social security system (or “iron rice bowl”) that companies were required to provide employees. The reforms led to higher household savings as the responsibility of caring for the elderly fell from businesses to households and local governments.

4.Corporate and market reforms have increased efficiency, and economic growth outpaced salary increases during the global economic crisis of 2008. These factors pushed up corporate savings rates.

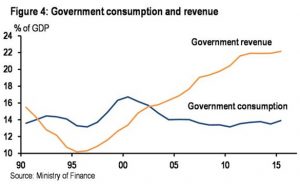

5.China’s 1994 taxation reform increased government income for good. But government spending has remained stable over the years, about 15 percent of GDP, leading to increased government savings and investment. (See figure 4).

The recent decline of China’s GNS

However, China’s GNS has dropped in recent years. Government savings have remained relatively stable at about 5 percent of GDP. The recent decline in GNS can be attributed to four factors:

1.China’s aging population (explained in detail later) and the gradual establishment of a national social security system.

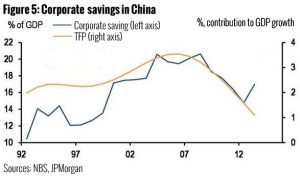

2.Cooling corporate profit growth. The 2008 launch of a 4 trillion yuan (US$ 598.42 million) stimulus package caused overinvestment and surplus production capacity in some industries, including iron, real estate, cement and coal, leading to a sharp decline in the rate of return on investments, according to the NBS and JPMorgan Chase. Declining growth in total factor productivity and weak corporate profits reduced companies’ ability to rely on retained earnings for financing of investments (Figure 5).

3.Liberalized interest rates and market development, which have expanded Chinese businesses’ access to external financing.

4.Slower growth of government income. The difference between government revenue and consumption — and thus government saving — has stabilized.

China must now determine whether the recent drop in savings rate is temporary, or whether it represents the beginning of a long-term economic decline comparable to 1990s Japan. During its decade of explosive economic growth in the 1980s, Japan’s GNS was also extremely high. By 2001, Japanese GNS had fallen to 25 percent of GDP, from 34 percent in 1991, and it has since dropped to 18 to 19 percent of GDP, according to statistics from the World Bank (Figure 6). The sharp decline of Japan’s GNS occurred more or less in line with the country’s “Lost Decades” of economic stagnation.

Other Asian countries, though, have experienced different outcomes. For instance, South Korea’s GNS has remained stable despite an aging population.

Demographic changes: a key driving force

Of the above-listed reasons, the changing age structure of China’s population has likely had the greatest impact on savings rates.

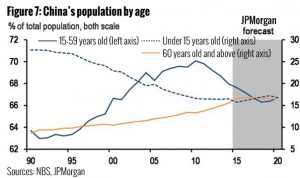

2011 was a landmark year for Chinese population issues. The number of Chinese citizens of working age, defined as 15-59 years old, as well as the proportion of working-age citizens within China’s total population, peaked in 2011, and began a slow decline thereafter, according to the NBS and JPMorgan Chase.

China’s one-child policy, implemented in 1979 and relaxed only in recent years, caused significant distortion in the Chinese population’s age breakdown. The proportion of Chinese citizens over the age of 60 increased from 10.5 percent in 2001 to 14.9 percent in 2013. It is expected to rise to about 16.5 percent by 2020 (see Figure 7).

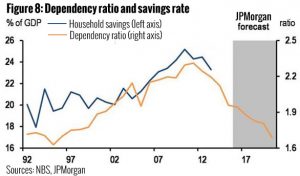

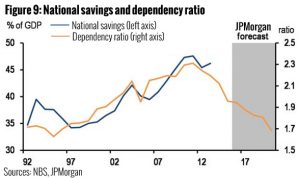

This demographic shift has changed China’s dependency ratio, or the ratio of citizens in the labor force to those above or below working age. China’s dependency ratio rose from 1.7 in the early 1990s to 2.3 in 2011, after which it began a slow decline. The ratio is predicted to fall back to 1.7 by 2020.

The dependency ratio is closely related to household savings (Figure 8) and overall GNS (Figure 9). If each working-age person must care for a higher average number of dependents (signified by a low dependency ratio), household savings will fall and expenditures will increase.

Even with the rapid demographic change, population change will exercise a predictable effect on savings rates. China’s household savings rate is predicted to fall from 23.3 percent of GDP in 2013 to 18 percent in 2020, JPMorgan Chase says.

Meanwhile, the GNS is expected to drop from 46.2 percent to 35 percent in the same period. Although 35 percent is still a high savings rate by international standards, the drop in GNS would have significant repercussions for China’s economy.

The consequences of a declining GNS

Falling savings rates will likely be one of China’s most significant macro-level challenges during the next decade, with a serious effect on economic restructuring and financial stability.

China’s debt from the last 15 years was accumulated during a period of extremely high savings rates, high investment, and rapid economic growth. If savings rates fall quickly over the next five years, investment as a percentage of GDP will also plummet, forcing extensive economic restructuring. If this happens, China will be forced either to rely on foreign debt or to raise the efficiency of its domestic investment.

As a result of recent net outflows from Chinese capital accounts, China is unlikely to choose the first option. The second option is more feasible, though its implementation would require significant supply-side structural reform.

China’s total debt has increased rapidly since 2008, with its ratio against GDP increasing by about 100 percentage points from 2007 to 2015. Due to climbing debt, forestalling financial risks has become a top policy priority.

The relative stability to date of China’s financial sector is due largely to high savings rates balancing rapid credit growth rates. If falling savings rates fail to elicit corresponding adjustments in debt and investment, financing costs will spike, increasing the burden of debt repayment.

Alternatively, China could increase foreign debt financing, but this strategy would increase the external vulnerability of financial risks. Regardless of strategy, managing debt and savings rates will be urgent priorities for China’s government in the coming decade.