Alicia García Herrero (Natixis) | China’s Two Sessions – the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) – took place from March 4-11 in Beijing. This year, the Two Sessions have been particularly important for understanding where the Chinese economy is heading, as new Premier Li Qiang delivered his first “Work Report,” which marked the beginning of a new economic era.

The Work Report signifies a departure from the previous decade under Premier Li Keqiang’s leadership and puts more emphasis on the supply side rather than demand side of the economy. The focus on “new productive forces” points to Chinese leaders’ new understanding of the country’s economic transition. From the Work Report, we see that China aims to double down on basic and advanced manufacturing while demand-oriented stimulus measures seem to be less relevant.

Foreign investors had been expecting China to announce fiscal and/or monetary stimuli to support its struggling domestic economy. But they are now confronted with the country’s further push towards becoming the factory of the world – and, this time around, for any kind of product, including the most advanced. Investor disappointment was felt right after the Work Report was delivered in a 2% drop in the Hang Seng Index, China’s most relevant offshore barometer of foreign sentiment.

Whether the focus on manufacturing production instead of consumption will be successful depends on the quantity of Chinese products the rest of the world will accept. By investing more in manufacturing, China will build additional capacity – adding to already existing overcapacity, which can be seen from the pervasive and persistent deflationary pressures in China’s upstream sectors, with producer prices having remained negative for nearly two years already. The reality is that, even with falling export prices, China has not managed to increase exports until very recently, opening a big question mark as to whether the rest of the world will willingly absorb China’s additional manufacturing capacity.

The protectionist forces that are being unveiled worldwide, starting with the US but expanding rapidly, will only make it harder for China to sell the products stemming from these “new productive forces.” Therefore, there seems to be an inherent contradiction between Li’s expectation that new productive forces offer the solution to China’s growing pains on the one hand and growing protectionism globally on the other.

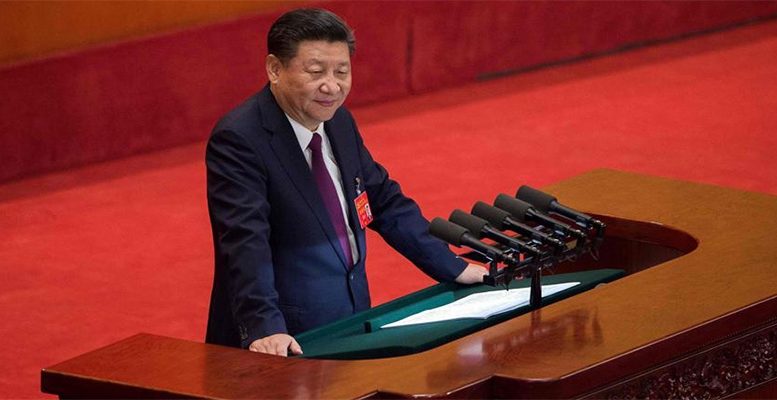

Chinese policymakers are not ready to jump into the unknown territory of “high-quality economic development” and abandon the country’s old-fashioned growth targets, especially given how much emphasis President Xi has put on the quality of growth. The emphasis on quality hinges on the determination of Chinese policymakers to move away from the real estate sector as the main source of growth and toward advanced manufacturing. However, keeping the actual GDP growth target at the same level as last year’s 5% points to a lack of confidence in moving away from the old model.

A much bolder move would have been first to recognize that China can no longer achieve the same GDP growth as last year because of relentless structural deceleration and then adjust economic plans accordingly. Moving to high-quality growth implies that some costs will need to be borne in terms of economic deceleration in the transition from a real estate-based model to a model that needs less investment and more consumption. China does not need more investment in a different sector (like manufacturing) as this will only delay the rebalancing of the economy.

Achieving the high 5% target will also be challenging because of cyclical and structural headwinds. However, the pressure on Li to maintain and hit a high growth target remains intact, even with the coincident aim of achieving more high-quality growth. Such pressure to grow above potential, mainly by doubling down on advanced manufacturing, is bound to create additional tensions with China’s major trading partners. China’s 5% growth target in 2024 will thus be harder to achieve than it was last year. If achieved, it will be thanks to the rest of the world willingly absorbing China’s excess capacity, but this is by no means certain. Even if it does happen, China’s increased focus on manufacturing will only create more capacity to absorb in 2025, making this growth model potentially as unsustainable as that of the real estate-led one, although for different reasons.