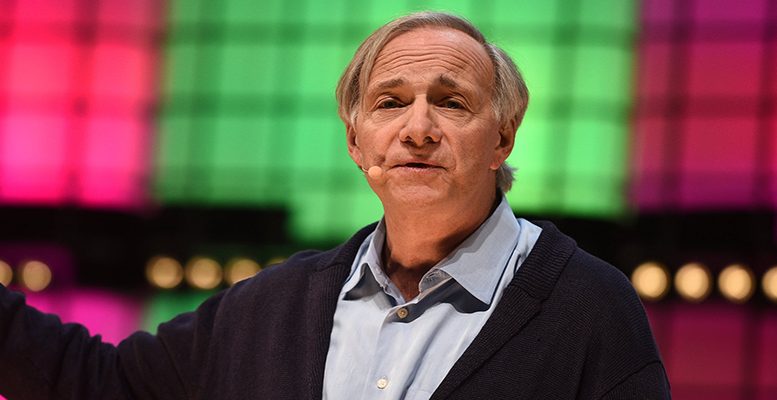

Many consider that his hedge fund, Bridgewater, is a sect. A sect in which the guru is the fund’s founder, Ray Dalio. A guru who is now semi-retired from the front-line of managing the fund, and dedicates himself to spreading his ideas about the world, life and the markets. Ideas which are captured in his best seller “Principles”, published in Spain by Deusto, in which he develops his philosophy of life and the markets in 608 pages with autobiographical touches.

It is likely that if Ray Dalio had not earned a fortune, which on 26 January the magazine Forbes estimated at 18.6 billion dollars (16.3 billion euros), these Principles would not have been taken seriously by anyone. But Dalio can always argue, like Cardinal Cisneros, that “these are my powers”. In his case, specifically, the power had been to have founded and directed the most successful hedge fund in the history of these investment vehicles. Last month marked the 70th anniversary of Alfred Winslow Jones – ex humanitarian volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, founding the first such fund.

Over three decades, the star fund of Bridgewater, Pure Alpha, has secured an average return of 12%. In 2018, a year in which the average hedge fund lost around 3% of value, and which closed with the Standard & Poor 7 % below where it had started, Pure Alpha grew 14.6%, albeit before commission charges.

Dalio claims to have invented a management model based on radical transparency. For his critics, it is no more than a cult of personality (his) and a hyper competitive climate (even for a hedge fund) concealed by grandiloquent language. Radical transparency, these apostates affirm, does not seem to have worked in the two cases of sexual abuse which Blackwater has had to deal with, one of which affected no less than one of Dalio’s designated successors, Greg Jensen.

But the undeniable success of Blackwater cannot be denied. If, as the refrain says, “the water will have something when you bless it”, it is not that Salio ahs something, but 18.6 billion dollars and the most successful hedge fund that has ever existed.

Your book much recalls the post-Stoics, like Epictetus or Marcus Aurelius, Have you read them?

No.

You never discuss your intellectual influences. Is there any philosopher that you could cite as a source of inspiration?

No. I am self taught. I like reading history and other things, I like looking at things from different perspectives. My perspective is based on experience and curiosity. I like travelling round the world, living experiences and reflecting on them with other people. I like history. I have read a lot of history, and through it I have learnt how things, and I have begun to have understood how things happen more than once, how they repeat. I know nothing about Stoicism, but the little I have heard sounds good. But I like to try to make my life the best possible and it doesn’t matter how many times I stop in the road to get there. I believe that pain plus reflection equals progress. And I think that I have internalised it. Every time something goes wrong, I ask myself what I have done wrong, and if I find the answer it is a real gem that I have. I have linked mistakes with learning.

So you have to fail to learn?

Yes! This is one of the main themes of the book. The other is to know what you don’t know.

To accept nature.

I believe that people’s worst mistake is to stick with ideas that have been shown to be mistaken. To be aware of what you do not know is more important that knowing what you do know.

History repeats itself?

Yes.

But not exactly the same. Otherwise it would be too easy. Especially in the markets.

I agree, not exactly the same. But the cause-effect relationship, yes. And there are two reasons people don’t see it. There are things which repeat themselves, but not with sufficient frequency within the life of one person for people to notice it. There are things which repeat themselves because what happened obeys causes which make this happen.

There is a clear cause-effect relationship?

I’ ve written a book about debt in which I explain how all the major debt crises – 48 in total – which we have suffered in the last 100 years are the same. It is like a disease. Let’s imagine a cancer. It is not that all cancers are the same, but that if you are a doctor and see them often you will see that they behave in a similar way. People don’t see this.

Why?

Because people don’t think in principles. People don’t reflect: “What kind of situation am I in? And what principles can I apply to confront this situation?” There is an enormous accumulated human experience which allows us to confront every situation, but we don´t do it.

Then the problem is to think “This time is different”, to quote the book on debt by former IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff and his assistant at Harvard Carmen Reinhardt.

The big mistake is not to understand the causal relationships. And the great tragedy is to see things happen more than once without examining how the cause-effect relationships repeat themselves. Things can be different, because the causes have changed and, therefore, the outcomes are different. The debt crises are to a large extent similar. If the 48 debt crises of the last 100 years are examined as if they were diseases, and if the average crisis is taken and the cause-effect relationships are examined, it can be seen when they are repeated and when not.

Some people – especially Nassim Nicholas Taleb – say that as human beings we tend to look for relationships between things which are not related. Doesn´t your line of though run the risk of falling into this error (assuming that Taleb is right and this error exists)?

In his book Fooled by Randomness, Taleb deals with the question: to see that because something happens ten times in succession, it is going to happen an eleventh time, without understanding the cause-effect relationships which have made it happen these ten time. We tend to choose the options which have given good results in the past. But that is because we do not understand distributions, how the numbers work. That is where superstition is born.

Let’ s turn to worldly realities. In you book you say that the President you admire most is Lee Kwan Yew of Singapore, because of the economic growth he promoted in his country, which converted it from a developing country to one of the richest in the world. What else do you admire about him?

His achievements are an extension of his personality, and I admire his personality. He was a good person, in the sense that he took upon his shoulders the responsibility of the welfare of his people without egoism. And he was also very realist. He saw things from an unideological perspective. His thinking was very clear.

But Lee was also an autocrat who was in power for four decades.

Lee was capable of achieving a balance others cannot. For example, when we talk of autocracy. Let’s be clear: one can debate which is better, autocracy of democracy. Plato said that the best leader is a benevolent despot. Lee Kwan Yew was able to be a strong leader and create democracy. Singapore is a democracy with strong leadership. It is not easy to secure this balance. Is it an autocracy? Is it a dictatorship? It is definitely not a dictatorship. It is a democracy, but with leaders with strong principles. In the situation in which Lee was, there were two options: leave things as they are or change them so that they are as they are now. And in that region there was nowhere civilised when he arrived. There were no civilised people, and the civilised foreigners had nowhere to go. When he arrived in power, people pissed in the lifts in Singapore. His project was to create a good citizenry. Some see this as autocracy, but the reality is that he installed norms in Singapore such that if you behave yourself you can have much liberty.

That sounds like China.

It is the same in China today. If you behave well, you can have lots of freedom. The Chinese culture is influenced by Confucianism, which means that, which describes a Chinese leader, “the country is ruled like a family. The difference between us and Americans is that you value the individual. For you the most important is, in fact, the individual. If you take the word “nation” in Mandarin, it is formed by two syllables: “family” and “state”. We, in the highest levels of government, feel paternal, and in governing we think about “what is best for the country”. In the US you what is good for society. In China we ask what is good for the family”. Thus the system is much more top-down. And it gives the impression of being autocratic. Because they do not believe in democracy. It is something linked to Confucianism, which means they have a vision of the world with what we could call “Chinese characteristics”. And this is seen in both China and Singapore. What Lee Kwan Yew created was a hybrid between something we could call “Chinese characteristics” and democracy.

In your book “Principles” you say that every organisation runs the danger of becoming an autocracy. Have you been afraid of becoming an autocrat at Bridgewater?

Me? Never. I need everyone to question me. I need people to know they don´t agree with me and challenge me. I have been a revolutionary, I have a meritocratic mind set. I grew up in an environment which was not conventional, like the Apple ad with Steve Jobs “Think about things differently”. I was not a member of the establishment, and the market always left me clear when I was tight and when I wasn´t. I cannot respect people who always agree with me, because in that case I have to micromanage them.

Recent years have not been good for hedge funds.

Above all, I do not believe that the average of any sector can produce an alpha. So, hedge funds cannot all produce an alpha, producing an alpha is by definition a zero sum game. It is not like the stock market. You cannot say “this has been a good year because profits have risen and interest rates have fallen”. I don’t know. Perhaps it’s linked to the fact that a limited number of assets, and I’m referring to technology assets, have evolved very well in comparison to the rest of the market … Perhaps it has to do with the fact that at first we had very low volatility and then very high … I’m not sure I have an answer.

You have been very critical about the results that the free market economy is generating for a large part of society.

Inequality today is greater than at any time in the last nine decades. You have to go back to the thirties to find greater inequality. If there is an economic slowdown there is very little margin to act. We have been more successful in securing a stable economic environment with low inflation than we have been in securing an environment with stable growth.

*Image: David Fitzgerald/via Flickr