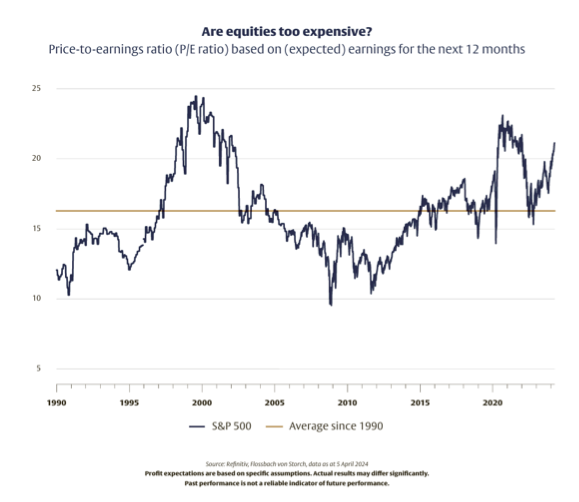

Bert Flossbach (Flossbach von Storch) | The AI boom has also had an impact on the equity markets, and not just on the supposedly immediate winners. The valuation of US equities, which make up a good two-thirds of the MSCI World Index, has recently risen further and, with a price-to-earnings ratio (P/E ratio) of 23.4, has reached an above-average level, even in an historical context.

It is now common knowledge that equity investors look ahead and attach greater importance to the expected success of companies than to last year’s earnings. As analysts are naturally confident in their earnings estimates, they almost always expect corporate profits to rise in the future. They currently expect corporate profits to rise by around nine per cent over the next 12 months, which is a record level and is due not least to the high growth expectations for the index heavyweights. The forward P/E ratio is therefore 21.5, which is still above average in an historical context (figure).

This is also reflected in the high concentration in the equity indices, which is typically much higher at the end of a long upswing than at the beginning. For example, the share of the 10 largest S&P 500 companies (measured by market capitalisation) in the index rose from 18 per cent in 2014 to 32 per cent most recently. At the end of the technology boom at the turn of the millennium, it was 27 per cent. The equally weighted index variant (S&P 500 Equal Weighted) naturally has no concentration risk and, with a P/E ratio of 17.5, has a significantly lower valuation than the market value-weighted S&P 500 Index.

This does not mean that the valuation of the S&P 500 Index has to fall back to its long-term average, but it does emphasise that the bar for corporate earnings is particularly high here and that the air on the stock market has become thinner. After five months of almost uninterrupted rises in the equity markets, a correction has become not only more likely but also more desirable. It could allow the shares of first-class companies, whose prices have already priced in a great deal of growth optimism, to fall back to more attractive valuation levels and thus open up investment opportunities.

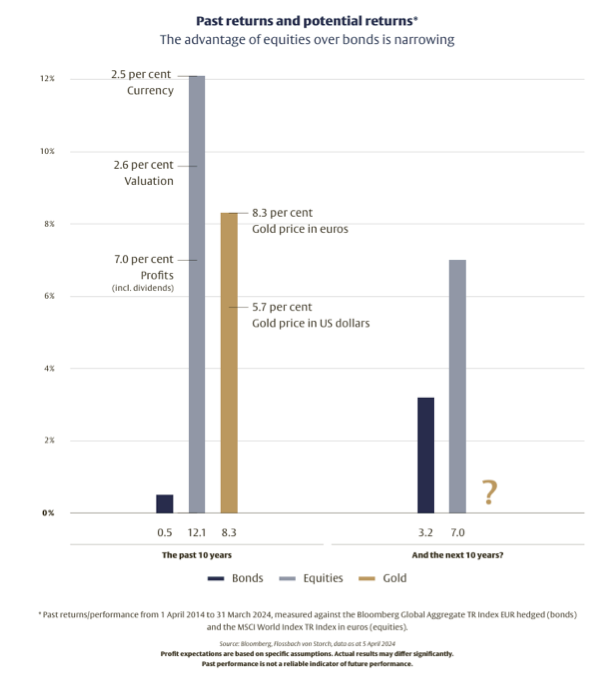

Over a longer period of time, the development of corporate earnings is by far the most important factor for share-price development. But even over 10 years, valuation and currency fluctuations can have a noticeable positive or negative impact on overall returns. A look at the performance of the MSCI World Index over the past 10 years illustrates this.

Including dividends, the index has increased by a good 12 per cent per annum (p.a.) over this period, although profits and dividends have risen by only seven per cent. Of this, 2.5 per cent is attributable to currency gains, while a further 2.6 per cent resulted from an increase in valuations.

However, valuation gains cannot be amortised indefinitely. If valuations rise above a “normal” level, this is at the expense of future performance potential. When determining the long-term return prospects of equities, one should therefore not expect a sustained tailwind – i.e. a further increase in valuations – but rather a slight decline. Long-term currency developments are difficult to predict. However, a sustained appreciation of the euro against all major investment currencies seems very unlikely, which is why a global equity portfolio offers sensible currency diversification.

In this respect, the long-term “predictable” return potential of equity investments is determined by the development of corporate earnings and current dividend distributions. Past earnings performance can serve as a point of reference, whereby we use the S&P 500 Index due to the better data basis. The companies included in the index have each increased their profits by a good seven per cent p.a. over the past 10, 20 and 30 years. A similar rate of growth for the next 10 years can therefore be considered a plausible estimate, resulting in a doubling of corporate earnings. If the valuation remains unchanged, this would also apply to share prices.

To be on the cautious side, a decline in valuation should be factored in for US stocks. With a more moderate P/E ratio of 18, the S&P 500 Index would still rise by 67 per cent or 5.3 per cent p.a. Including dividends, this would result in a total annual return of around seven per cent (in US dollars). This is well below the total annual return of the past decade of a good 12 per cent (in US dollars).

A realistic return expectation for shares over the next 10 years is therefore around seven per cent p.a. This is based on rising corporate earnings and dividends, a slight fall in valuation, and ignores the incalculable currency contribution.

With bonds, the maths is comparatively simple. Anyone who buys a portfolio of solid euro bonds with a remaining term of around 10 years today and holds them until maturity can expect a good three per cent return p.a. by then, which is significantly more than the half a per cent in the past decade. The only unknown factor is the level of the reinvestment interest on the annual coupon payments, if one disregards the unlikely bankruptcy of numerous solid debtors.

No serious price forecasts can be made for gold. Over the past 10 years, investors have been able to enjoy an annual gold price increase of more than eight per cent in euro terms. Looking ahead, we should not expect that much again. For us, gold investments are not focused on returns, but on their insurance character as part of a diversified investment strategy.

Equities remain the most attractive asset class for long-term investors, as they also offer protection against unexpectedly high inflation. However, it is unlikely that the yield advantage over bonds over the next 10 years will be as high as in the past decade. We will know in 10 years’ time.