*This is the second of three articles in which the author will analyze China’s investment, lending and infrastructure initiatives in Southeast Europe for Macropolis. The first contribution focused on China’s ‘Gateway to Europe’ via the Port of Piraeus in Greece.

The second part will now look at China’s emerging footprint in neighboring countries such as Serbia, FYR Macedonia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. All three countries are land-locked states which offer a different set of opportunities and challenges for the extension of China’s Balkan Silk Road.

The final piece will place China’s activities in the region in the wider strategic context of challenges for the European Union, multilateral lenders such as the EBRD and European Investment Bank as well as Russia.

The three contributions are based on a report which the author has written for the EBRD in London. The full report is available on the web page of the EBRD: http://www.ebrd.com/news/2017/what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-means-for-the-western-balkans.html

Jean Bastian via Macropolis | In one major respect, the FYR of Macedonia is an outlier in the Chinese investment and economic cooperation strategy. Back in the early 1990s, the political authorities in Skopje sought international recognition for their country while the so-called ‘name recognition dispute’ with Greece was escalating. One means to achieve this objective was to simultaneously recognize Taiwan, which in turn was prepared to provide considerable financial resources to Macedonia. This strategy was later abandoned by successive governments in Skopje in favour of a gradual rapprochement with China.

The most recently available international trade data for the FYR of Macedonia illustrates that China was the country’s fourth largest trading partner in 2016 (treating the EU-28 as one partner), reaching a total of Euro 424 million. The trade balance is almost exclusively tilted in favour of China, which is the FYR of Macedonia’s third largest import originator, while it features in ninth position as Macedonia’s export destination.[1]

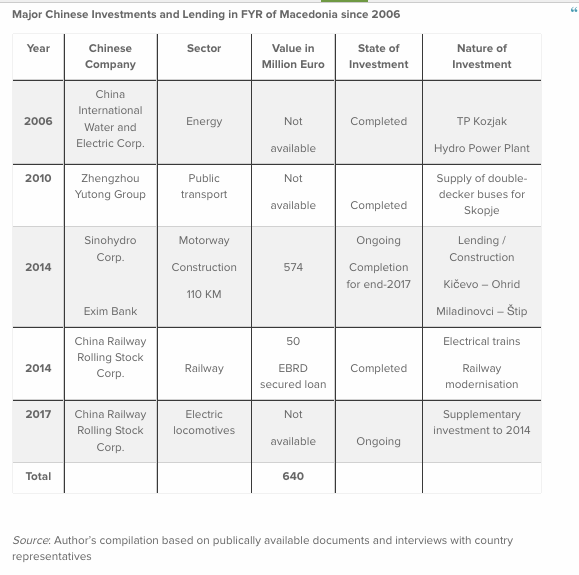

As a land-locked country in the Western Balkans, the FYR of Macedonia presents specific challenges for enhanced economic activities by Chinese companies. Maritime considerations can be excluded; terrestrial infrastructure projects are the main priority. The focus rests on establishing branches of logistical corridors in sectors such as energy, motorways and railway modernization.

These corridors seek to connect the FYR of Macedonia with wider corridor initiatives along the Balkan Silk Road initiative. Seen from this perspective, Chinese investments in FYR of Macedonia have a strategic focus. The country represents one of the connecting links between port facilities being expanded or acquired in neighbouring countries and transport infrastructure projects. Sino – FYR of Macedonian economic cooperation dates back a decade when the first major project was realized in the energy sector.

Subsequent infrastructure projects have focused on road construction and railway modernization. These projects form part of regional, rather than country-specific initiatives that Chinese companies and banks are supporting. Railway modernization in FYR of Macedonia is a result of the agreements between Hungary, Serbia and China along the Budapest – Belgrade Corridor X initiative. When driving from the Greek – FYR Macedonia border crossing of Bogorodica near Gevgelija to the capital city Skopje, the construction sites of the A2/A3 highway from Kičevo to Ohrid (57 km) and the Miladinovci to Štip motorway are easily identifiable.

Financed through lending by Exim Bank, the two infrastructure projects are being built by Sinohydro Corporation. Granit and Beton from FYR of Macedonia perform much of the roadwork as subcontractors. The Miladinovci to Štip highway will dramatically reduce travel time from the capital Skopje to Štip, which is the largest city in the Eastern region of the country.

Launched in March and June 2014 respectively, the two projects are expected to be completed by end-2017. They form part of a larger programme to build a European corridor 8, East-West throughout FYR of Macedonia. They provide an East-West corridor that supplements the South-North corridor that was financed by the EU’s European Agency for Reconstruction in early 2002.

In 2014, the government in Skopje purchased four Diesel and two electric trains from the Chinese company CSR Corporation. The acquisition was financed by a Euro 50 million loan secured by the EBRD in London. This investment was the second large procurement of transportation vehicles awarded to a company from China. In 2010, China’s Zhengzhou Yutong Group was chosen to supply the capital city Skopje with 202 retro-looking double-decker buses for its public transport system.

Serbia: China’s Emerging Financial, Trade and Infrastructure Footprint

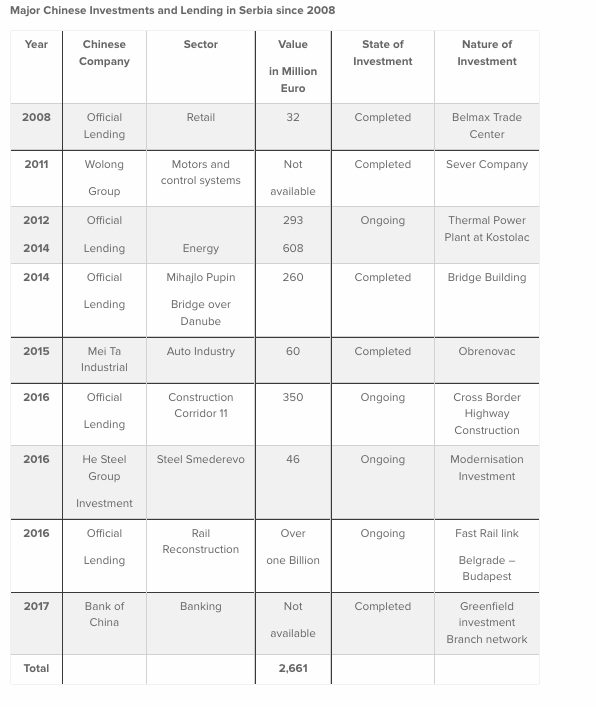

China’s economic cooperation with Serbia has expanded significantly since the signing of a strategic partnership agreement in 2009. The bilateral cooperation agreement included infrastructure investments. Primarily project-based on the transport sector, the partnership received extensive state-to-state funding from a variety of state-owned Chinese banks. The third China-Balkans Summit under the 16+1 umbrella was held in Belgrade in December 2014.

Seen from a Chinese perspective, the Serbian market is rather small and it is a land-locked country. But it is not size nor geography that matter. Connectivity is the underlying issue: Serbia is an attractive partner since it has trade agreements with the EU, Turkey and Russia. It also enjoys a level of political stability that is not a given in neighbouring countries. Equally, both countries have established a visa free regime effective since January 2017.

The most recently available international trade data for Serbia illustrates that China was the country’s fourth largest trading partner in 2016, reaching a total of Euro 1,469 billion. The trade balance is almost exclusively tilted in favour of China, which is Serbia’s second largest import originator, while it does not feature in the top ten positions as Serbia’s export destination. [2] The share of Chinese investment (Hong Kong included) in total FDI to Serbia was 3.1 per cent in 2015 and rose to 9.2 per cent in 2016. This increase is primarily attributed to the acquisition of the steel mill Zelezara Smederevo by China’s He Steel Group for Euro 46 million in 2016.

In January 2017, the Bank of China (BoC) opened its new branch in Belgrade. It is a subsidiary of the fully licensed BoC bank located in Hungary. BoC has a strategic partnership pact with the Hungarian authorities since January 2017. This form of indirect investment should for the time being be seen as a political decision in which a Chinese bank establishes a representation in Serbia, only gradually building up its financial operations in the medium-term.

Serbia’s importance to China’s BRI has repeatedly been emphasized by Chinese President Xi Jinping, most recently during his three-day state visit in June 2016. Xi sees Serbia playing a leading role in the cooperation between China and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

Source: Author’s compilation based on publically available documents and interviews with country representatives

Source: Author’s compilation based on publically available documents and interviews with country representatives

Two major infrastructure projects illustrate the level and format of Sino-Serbian cooperation. One concerns the construction of the Friendship Bridge over the Danube in Belgrade in 2010. It was carried out by the Chinese state-owned enterprise China Road and Bridge Corporation. The loan for the USD 260 million investment was provided by the Export-Import Bank of China.

The second project is the Belgrade-Budapest high speed railway initiative. For both cities, such a project has been on the agenda for more than a decade. Until recently, it did not take off, primarily for lack of financing capacity. But in November 2016, China’s Export-Import Bank agreed to fund 85 per cent of the bilateral project.

However, this flagship 350 km project has triggered an investigation launched in January 2017 by the European Commission against Hungary. The probe is looking into the financial viability of the USD 2.89 billion project. The Commission in Brussels contends that Hungary is in breach of EU laws by not initiating a proper public tender for a transport infrastructure project of such a financial magnitude.

Bosnia and Herzegovina: How China Seeks to Overcome the Complexities of BiH

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) does not yet feature prominently on the radar of Chinese economic activities in Southeast Europe. Foreign direct investment (FDI) has come from Russia in the energy sector. Gulf states have started to invest in real estate and shopping centres. Turkish FDI is mainly concentrated in small- and medium-sized enterprises’ (SME) activities.

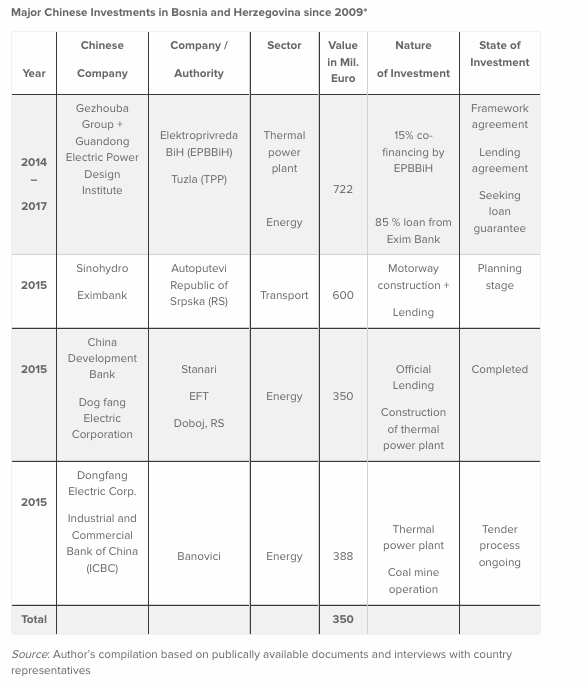

In the case of BiH it is necessary to distinguish between intended or reported (by BiH media) investments on the one side, and the real, but limited economic activities of Chinese companies in the country on the other side. A major obstacle for the realization of further projects rests in the complex and time-consuming political and administrative structure of the country, its entities and (in the Federation entity) its cantons.

The most recently available international trade data for Bosnia and Herzegovina illustrates that China was the country’s third largest trading partner in 2016, reaching a total of Euro 571 million. The trade balance is almost exclusively tilted in favour of China, which is Bosnia and Herzegovina’s third largest import originator, while it does not feature in the top ten of Bosnia’s export destinations. [3]

Lending flows from China to Bosnia and Herzegovina are geographically concentrated. So far, two projects are located in the smaller Bosnian Entity, Republika Srpska (RS), and two in the Federation of B&H. While the latter two focus on thermal power, the former two concern motorway construction and a thermal power plant.

In 2014, Bosnia’s Federation selected a consortium of China’s Gezhouba Group Company Limited and Gunagdong Electric Power Design Institute as the preferred bidder for the construction of Unit 7 at Tuzla coal-fired power plant. The thermal power plant project is located Northeast of Sarajevo in the country’s third-largest city.

In November 2016, the Bosnian power utility Elektroprivreda BiH (EPBBiH) signed a framework agreement for the construction of the 450 MW unit at the existing Tuzla thermal power plant (TPP) with China’s Exim Bank. EPBBiH would finance 15 per cent of the project. A loan from China’s Exim Bank would cover the remaining 85 per cent. The project has a total worth of Euro 722 million. [4] If implemented on these reported terms, the project would be the largest post-war foreign direct investment in BiH.

The only large infrastructure project that has been completed with Chinese involvement concerns the Stanari thermal power plant in Doboj, Republika Srpska. The project started in 2014 and was completed in 2016. Power production has started. The China Development Bank provided a Euro 350 million loan to construct the facility. China’s Dongfang Electric Corporation was hired by the private owner – Energy Financing Team (EFT) – to build the facility. It is thus a private project in RS with no sovereign state guarantee provided.

At the level of the State of BiH there appears to be no strategic roadmap vis-à-vis the question on how to deal with Chinese activities or project proposals. Rather, a case-by-case approach seems to prevail. In one specific project in RS, the Chinese involvement in the Stanari thermal power plant underlines that the Chinese are so far only prepared to take construction and limited financial risks, but are not willing to simultaneously take on operation risk.

In general, the Chinese activities to date in BiH are limited, signifying more rhetoric than substance. China is only at the beginning of a much larger engagement in the region of Southeast Europe. However, doubts remain about the extent to which this will benefit BiH. The political instability of the federation, unresolved constitutional challenges and geographical reasons [5] are seen as drawbacks that limit an expansion of Sino-Bosnian economic cooperation.

Do spill-over effects from China’s engagement in Southeast Europe materialize?

China’s engagement in Southeast Europe is multi-layered. The region can be seen as a testing ground for China’s growing European ambitions – whether through trade, the construction of roads, investments in ports, power grids or railways. As China implements its BRI along the Balkan Silk Road spill-over implications materialize over time in particular in terms of regional trade, links to China’s manufacturing sector and its commodity exporters.

In Greece and Serbia spill-over effects are feasible and sustainable over time. The growing Sino-Balkan relationship has diverse implications for individual countries, depending on size of the domestic market, demographics, geographical conditions (e.g. port accessibility or land-locked), level of political stability and progress made in the EU accession process. The multiplier effect of major infrastructure investments only manifests itself over time.

The commercial success of the port of Piraeus in Greece following Chinese investments almost a decade ago is an outlier in that respect. The expansion of the port in terms of building additional peers and increasing the volume of container traffic has created sustainable spill-over effects, e.g. regarding SME development and job creation. But in other countries most local workers on Chinese infrastructure projects represent low-skilled jobs such as trench-digging or lorry driving.

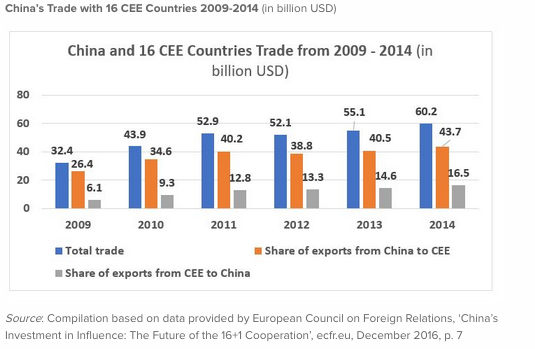

The major contribution of China’s BRI activities in the region of Southeast Europe is the facilitation of closer trade links. Compared to 2009 levels, total trade between China and countries from Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe almost doubled (see table above). The aggregate data suggests that the volume of exports from the 16 CE&SEE countries to China increased by more than 120 per cent during that period. The marked increase in overall trade volumes could be read as a ‘success story’ for all concerned. But such a conclusion is premature. The increase in trade between China and the CE&SEE countries is highly concentrated on five states participating in the 16+1 framework, i.e. Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Romania who constitute 80 per cent of these trade exchanges. [6]

Therefore, while trade between China and countries in the Balkans is increasing, the spill-over implications of improved trade relations have a long way to go until they can approximate levels attained in neighbouring countries such as Poland, Hungary or the Czech Republic. One could further argue that with the exception of Serbia, the critical mass of domestic market size and its growth potential just does not exist in countries such as FYR of Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina or Montenegro and Albania.

Thus, trade-related spill-over effects in these countries can be expected to remain limited and their increase will rather depend on pooling resources between countries in order to attain critical mass. Furthermore, China’s emerging focus on this set of countries must rather be seen as preparing the infrastructure network in order to utilize them as transit hubs or transit networks to move Chinese goods, services and personnel.

The realisation of Chinese-financed transport infrastructure projects will have positive spill-over effects on cross-border trade capacity. Investment in ports, roads, airports and their connectivity should reduce the cost and duration of transportation, thereby potentially contributing to higher trade volumes between China and the Balkan economies. Landlocked countries such as Serbia, FYR of Macedonia or Bosnia and Herzegovina should also benefit in terms of cross-border regional trade from the reduction in transportation time and costs. A further medium-term spill-over effect could be the establishment of free trade agreements (FTA) between China and the 16 countries in CEE as well as the conclusion of bilateral visa liberalisation regimes (which already exists between Belgrade and Beijing).

However, a further note of caution on the countries’ rising trade exposure with China is warranted. The spill-over implications of increased trade with China is based on the assumption that China does not become a source of shocks. As Blagrave and Vesperoni (2016) observed, “China’s economic transition involves rebalancing, which implies that spillovers to different countries depend on their exposure to different sectors of the Chinese economy – secondary sector (predominantly investment) against tertiary sector (related to consumption)”. [7]

How China is establishing a financial footprint:

The BRI “Belt and Road Initiative” is a long-term political economy strategy that represents a fundamental shift in how China seeks to deal with countries, regions and continents on a global scale. The BRI is a “geo-economic and geo-political strategy, rather than just a soft power initiative”. [8] A grand design such as the BRI requires laying the foundations for a Sino-centric financial architecture. To that end Beijing has made considerable efforts to provide and diversify financial resources. BRI includes special lending schemes in excess of USD 50 billion and a Silk Road Fund worth USD 40 billion.

Moreover, China is establishing financial institutions that mirror its global development agenda. This includes the creation of the New Development Bank (NDB) as well as the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). [9] The setting up of the Development Bank of the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation complements this new financial architecture. These three institutions add to the financial firepower available to the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China.

At the domestic level, the presence of financial institutions from China in Southeast Europe is progressing at a slow pace. Overall, Chinese banks have so far hesitated to enter local markets in Southeast Europe. The prevailing modus operandi is debt financing of investments through banks operating from China (or Hong Kong) rather than establishing a network along the Balkan Silk Road. Equity funding is slowly gaining ground, notably in Greece and Serbia. Most importantly, lending from Chinese banks for infrastructure projects enables countries in the region to diversify their funding capacity beyond Europe.

A banking footprint is gradually being established. In the case of Greece, the China Development Bank (CDB) signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Bank of Greece in July 2016. In Serbia, the Bank of China opened a new branch in Belgrade in January 2017. Financial connectivity is also being facilitated by the creation of two Sino-CE&SEE Investment Cooperation Funds, first in 2012 and most recently in 2016. The second of these funding channels has an initial investment capital of USD 11 billion, with a leverage ratio of one to five, seeking to raise 50 billion euros in project finance.