Rubén Segura-Cayuela (BofA Global Research) | Spain finally has a government, although with a razor-thin majority. This will be a coalition government comprised of the centre-left PSOE and the far-left Podemos, with the external support of several smaller parties, including Basque nationalists, and the implicit support (abstention in the government formation vote) of the secessionist ERC. The “easy”part of the job is done. The very challenging one, policy-making with thin parliamentary numbers, starts now.

We assume the government will be able to pass a budget that will facilitate its survival for at least a couple of years, but the risks are large. This government will try to reverse some of the more damaging social welfare cuts and particular elements of past structural reforms. Corporates will pay for some of the planned social expenditure increases and, although equities have already priced a lot of this in, we think there is room for underperformance. But we don’t think that, for now, rates markets should care much. We believe this government has enough safeguards in place to avoid large deviations on fiscal figures. True, the joint agreement contains measures that would potentially not be that growth-friendly and would rely heavily on tax increases (for instance undoing part of the labour market reform). However, a fragmented and polarized parliament and a very thin majority for this government both place constraints on the extent to which a left coalition government can deliver.

But we remain concerned about the medium run. This is not new – we have been for a while and it is not something that is exacerbated by this new government. Policy paralysis has dominated Spain for the past few years. Reforms and fiscal adjustments are easy to implement with strong growth and a very supportive central bank, along with years of effective ammunition ahead. They are also easier when political fragmentation is not entrenched and Catalonia is not a key divisive issue for political parties. This is not the situation now. Vulnerabilities remain and, without the strong majorities required to deal with these issues, it is hard to see any progress being made any time soon. Political dynamics are not conducive to more supply-side reforms and the required fiscal adjustment. This will leave the Spanish economy vulnerable to external shocks.

But, if anything, the current parliamentary configuration will feed into the political catch-22 Spain faces, making addressing those challenges even more difficult even in the medium run: the key issue dominating politics right now in Spain is Catalonia, which is polarizing politics further. The different stances on how to deal with Catalonia and the secessionist push there make it extremely hard for strong majorities to be built around the key reforms needed. But the new government will need to rely heavily on the support of both nationalist and secessionist parties if it wants to survive and pass a budget. This could further fuel that polarization and make it even harder to form the large majorities needed to address the key challenges facing the Spanish economy.

Spain has a government, now what?

The first question we get from clients on the Spanish government is whether it will survive. And recent history tells us the situation will remain fluid. Pedro Sanchez took office by winning a confidence vote on the previous centre-right government with the support of most of the same parties that have supported him now. But when trying to pass a budget for 2019, the left secessionist ERC failed to lend their support and this triggered the first of the two very recent elections. Are we going to see a repeat of this?

While the situation will remain fluid, we work on the assumption that this time is different and that the budget has probably already been discussed with ERC. In any case, there will be many opportunities for us to be proved wrong. There is the ongoing risk of elections in Catalonia. A bad result there for ERC could provide the incentive to drop support for the Spanish government, for instance. In any case, it will be very hard for this government to last the full term. But passing a first budget could at least allow the government to stay in place for two years.

The second recurring question we get from clients is whether, given the far-left is part of the coalition, this is going to be a government that is fiscally irresponsible and damages growth prospects. We are not too worried, for several reasons. First, Podemos, when negotiating the coalition agreement, dropped most of the proposals that were more worrying for investors. There is no longer any discussion of a tax on banks or the need to make Bankia a public development bank, for instance,

Second, the government configuration entails many safeguards, which we read as a clear message that, while this government will try to reverse some of the more damaging social welfare cuts and particular elements of past structural reforms, it will do so in a responsible way. The Portuguese example seems the right framework to watch. Indeed, Nadia Calvino will be deputy prime minister for economic affairs, overseeing most of the relevant reforms. Podemos has been handed none of the key ministries. There is now a new Ministry for Pensions (with the pension system being a key fiscal challenge) and the minister is the former president of the well-respected independent fiscal council, Jose Luis Escriva. And the joint policy programme by the two parties in government clearly states the need to be fiscally responsible and meet commitments with European rules.

What to expect?

The government has a comprehensive economic agenda. Among others, we would flag a few important elements:

- A progressive minimum wage increase towards 60% of the median wage;

- The linking of pensions to inflation and the undoing of some parts of the previous pension reform. There will be a new reform of the system;

- The creation of new taxes (financial transaction tax, digital tax);

- Reform of the rental market, including the possibility of price controls to avoid some of the large increases we are seeing in tourist destinations in particular;

- An undoing of some of the more extreme elements of the 2012 labour market reform;

- The creation of an income guarantee scheme for those families in the lower part of the income distribution;

- Reform of the energy sector to reduce some of the distortions in the system, including some of the existing subsidies and capacity payments. It will also try to promote self-generation and renewables;

- Higher de facto corporate taxes (minimum of 15%, 18% for banks and fossil fuel companies), together with some restrictions on deductions; and.

- Higher income taxes for the top of the income distribution.

Given the very thin parliamentary numbers, each of these measures will likely need to be negotiated one by one and test different majorities. Basque nationalists are unlikely to support the less growth-friendly measures. It remains to be seen whether the government can find an alternative majority without them. The razor-thin majority places constraints on what a left coalition government can deliver in terms of that agenda.

What to expect on the fiscal side?

With the most important measures described above, the key question is how much deficit slippage we should expect. It will take a couple of months before the government puts forward a budget, but we can use the proposal for 2019 as a basis of what to expect.

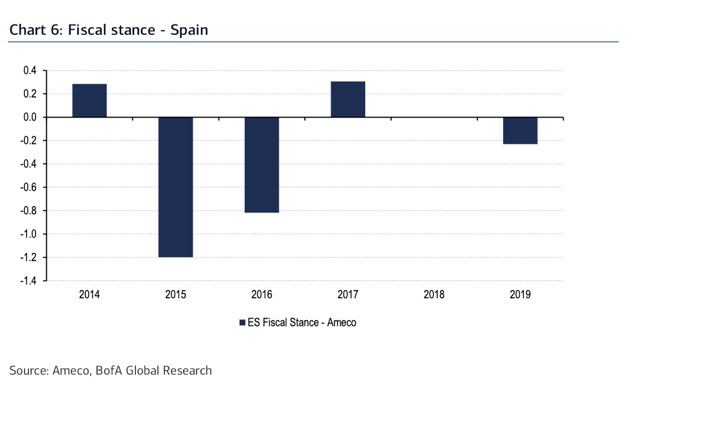

Back then the budget proposal, despite containing most of the expenditure-increasing measures being proposed now, also included similar revenue-increasing measures. The result was a structural budget improvement of 40bps of GDP. We questioned back then the magnitude of some of the revenue-increasing measures. The European Commission (EC) did the same (Chart 6). But still that budget was consistent with no deterioration of the structural budget. We would expect something similar this time.

We would also expect the budget to demonstrate a clear attempt to maximize flexibility within existing rules. The EC could question, as it does with many countries, some of the numbers, but any differences between the EC assessment and the current draft budget would be within the margins of limited magnitudes, implying room for a reasonable compromise down the line.

Hence, we are not particularly worried about this budget. The real problem is that Spain has not made any meaningful fiscal adjustment since 2014.

The medium term is what matters: some things have changed, others haven’t

There have been four elections in four years, and many things have changed since the first one. Growth is now less than half what it was at the end of 2015 (we expect growth of 1.6% this year). The budget deficit was fast declining then, owing to the cyclical backdrop, but this is barely the case now (we expect a very modest reduction for 2019, and something similar in 2020). QE had just started and there was plentiful ammunition, but the ECB has mostly run out of firepower now. Political fragmentation has continued to complicate policy-making. And the Catalan “issue” has become central to Spanish politics, making collaboration between different parties extremely complex.

But some things never change and most of what we were worrying about four years ago still holds. Indeed, back then we argued that the strong political consensus needed to address the pending challenges facing the Spanish economy was unlikely to be built any time soon and, without further progress, this would leave the country vulnerable to potential shocks in the medium run. We expected little progress on economic policy and even less on structural fiscal adjustment. And this is not far from what transpired

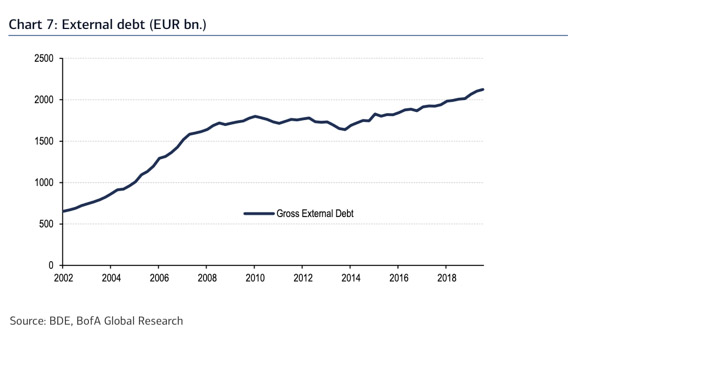

The different context matters now. Reforms and fiscal adjustments are easy to implement with strong growth and a very supportive central bank, with years of effective ammunition ahead. They are also easier when political fragmentation is not entrenched and Catalonia is not a key dividing issue for political parties. Spain has the largest structural deficit in the Euro area. Its economy’s external fragility (large external debt) also makes it vulnerable to confidence shocks.

And, if anything, the current parliamentary configuration will feed into the political catch-22 Spain faces, making it even more difficult to address those challenges. The new government will need to rely heavily on the support of nationalist and secessionist parties if it wants to survive and pass a budget. This could further fuel that polarization, making it even harder to form the large majorities needed to address the key challenges facing the Spanish economy.