David Rees (Schroders) | Financial markets in the emerging world suffered a wobble earlier this month. It followed the belated “blue wave” in the US election which appeared to clear the way for a large fiscal stimulus, and sparked a sell-off in the Treasury market.

The bout of volatility harked back to the Taper Tantrum that rocked EM markets in 2013. Fears of a repeat, as the US economy recovers this year, have become a major concern among investors.

We remain relatively dovish on the outlook for Federal Reserve (Fed) policy; we forecast no increases in interest rates for the next three years, with the tapering of asset purchases as part of quantitative easing set to only begin in spring next year. But it is at least worth considering the spill-over to EM if the brightening outlook for the US economy causes the Fed to withdraw its extreme policy support sooner than previously assumed; beginning with a tapering of its asset purchases this year.

A sudden jolt in the Treasury market would be likely to spark a period of global risk aversion and EM assets would undoubtedly come under pressure.

Higher risk-free rates as a result of a further sell-off in Treasuries would dampen some enthusiasm for risky assets such as those in EM. However, improved macroeconomic fundamentals suggest that EM would bounce back more quickly than in 2013.

Why did emerging financial markets “wobble” in early January?

Democratic Party candidates secured victory in two run-off elections in the US state of Georgia to give the incoming Biden administration wafer-thin control of the Senate.

The belated “blue wave” appears to have cleared the way for a substantial fiscal stimulus. That saw the yield of 10-year Treasuries climb by 20bp to almost 1.14% in the space of a week – the highest in a year – as the prospect of a faster economic recovery, along with higher inflation and debt, led to speculation that the Fed would have to unwind its large policy support sooner than expected.

The sell-off in Treasuries coincided with a wobble in EM financial markets. It stirred painful memories of the Taper Tantrum in 2013 when then-Fed chairman, Ben Bernanke, caught investors off-guard by telling Congress that asset purchases included in Quantitative Easing could be reduced.

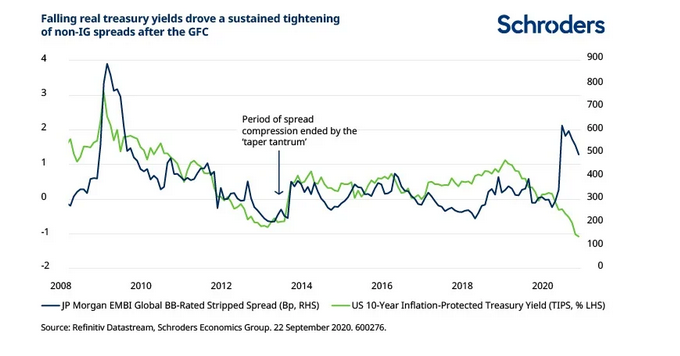

That sparked a sell-off in the Treasury market, which saw nominal 10-year yields climb by about 100bps in the space of three months as real yields surged.

Fears that the era of easy money that underpinned a hunt for yield and drove strong inflows to EM during the preceding three to four years was about to end saw investors take flight and triggered a sell-off across financial markets. Equities tumbled, credit spreads widened and pressure in foreign exchange markets forced central banks in several EMs to raise interest rates in order to protect their capital accounts.

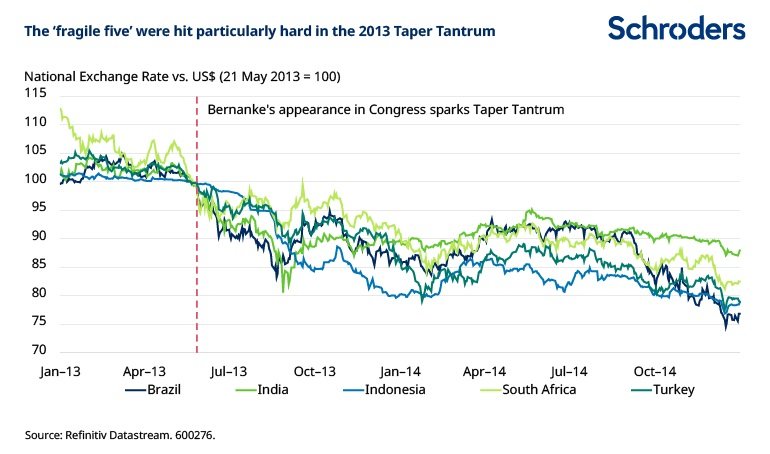

The effects were particularly severe in those EM, such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, South Africa and Turkey (the “fragile five”), that had built-up large current account deficits that were funded by short-term capital inflows. This left them vulnerable to a “sudden stop” in capital flows.

We noted in our Q4 forecast update that another Taper Tantrum was an obvious risk scenario that would have a negative impact on EM economies and markets. This remains a risk scenario that we continue to track. However, there are at least three reasons why we do not expect a repeat of the severe market volatility and lasting economic damage experienced in 2013:

1) The Fed is not about to take away the punch bowl

First, the Fed is likely to tread more carefully than it did in 2013. There are of course question marks about how long the Fed can really keep a lid on extremely low bond yields as the economy recovers. And there is always a risk that mis-communication by Federal Open Market Committee members will unsettle investors at some point in the future. However, the Fed’s new Average Inflation Targeting (AIT) framework implies that policymakers will want to see the whites of the eyes of inflation before withdrawing policy stimulus and it seems likely that financial repression will continue as fiscal needs dominate the agenda in the US.

There will be bumps along the way, but this suggests that real bond yields in the US will remain negative for some time to underpin demand for risky assets such as those in EM.

2) Flows to EM have been subdued in recent years

Second, there is not a large positioning overhang in EM like in 2013.

Investing in EM has become a consensus trade in recent months, but the bigger picture is that capital inflows have been subdued in recent years. Certainly they have not been on the same scale as they were in the four years or so after the Global Financial Crisis.

The huge capital outflows during the Covid crisis prove that this does not preclude severe flight to safety in the event of a major external shock. However, it does suggest there is less risk of a Taper Tantrum leading to a prolonged period of capital outflows. In simple terms, the less capital that flows into EM, the less there is to come out.

3) The Covid crisis has cleaned up EM balance of payments positions

Third, and related to this, subdued capital flows to EM in recent years mean that economies have not had the means to fund large current account deficits and built up the kind of large external imbalances that were exposed in 2013.

Indeed, the Covid crisis has actually cleaned up balance of payments positions in most EM as deep recessions have caused imports to collapse and current accounts to move into surplus.

Structural current account deficits will re-emerge as economies recover, but as things stand most EM economies are relatively well placed to withstand capital flight. This suggests that currencies are not particularly overvalued at the moment and also reduces the need for central banks to unexpectedly hike interest rates in order to bolster the capital account.

That’s not to say that EM would be immune to a taper tantrum if it were to happen and some economies such as Turkey and Colombia still have external vulnerabilities. But these improved fundamentals suggest that the macroeconomic and market consequences ought to be less severe than they were in 2013.

As we noted last year, if AIT leads to a prolonged period of capital flows to EM then it is likely that this would lay the foundations for some kind of future shock as economic imbalances build. But this is a risk for 2022 and beyond.