China’s market drama started in June this year with the collapse of the Shanghai stock exchange, followed by frantic interventions by the Chinese authorities. As if the estimated $200 billion already spent on propping up stock prices were not enough, China found itself in another battle with the market, defending the RMB against depreciation pressures after the PBoC devalued the RMB by nearly 2% on August 11. The cost of the foreign exchange intervention to keep the RMB stable is estimated at $200 billion.

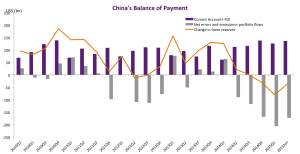

This adds to existing pressures on China’s international reserves, which though still extensive, have been reduced by as much as $345 billion in the last year, notwithstanding China’s still large current account surplus and still positive net inflows of foreign direct investment (Graph 1). The fall in reserves is not so much due to foreign investors fleeing from China but, rather, capital flight from Chinese residents. Another –more positive reason – for the fall in reserves is that Chinese banks and corporations, which had borrowed large amounts from abroad in the expectation of an ever appreciating RMB, finally started to redeem part of their USD funding while increasing it onshore. While this is certainly good news in light of the recent RMB depreciation, the question remains as to how much USD debt Chinese banks and corporations still hold and, more generally, how leveraged they really are a time when the markets may become much less complacent, at least internationally.

Public and corporate sector over-borrowing can be traced back to the huge stimulus package and lax monetary policies which Chinese economic authorities introduced during the global financial crisis in 2008-2009. A RMB 4 trillion investment plan focusing on infrastructure was deployed, but the real cost spiralled. The government also subsidized the development of several important industries and lowered mortgage rates to boost housing demand. At the same time, the PBoC substantially loosened monetary policy with interest rate cuts, reductions in reserve requirements and even very aggressive credit targets for banks.

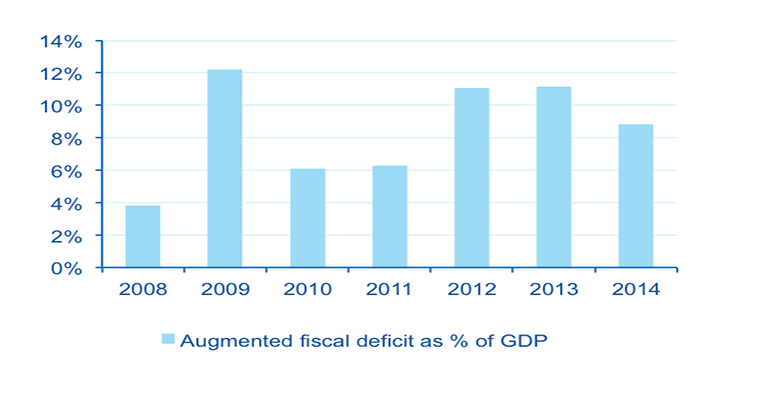

According to the authorities’ initial plan, the funds needed for the stimulus package would come from three sources: central government, local governments, and banks, with costs shared relatively equally. However in practice, given their limited fiscal capacity, local governments had to turn to banks to meet their borrowing needs. Banks could not decline loan requests from central or local government because of government ownership and control over most banks. In the meantime, government subsidies for specific industries boosted credit demand as firms in these sectors sought to take advantage of policy support and expand their production capacity. Mini-stimulus packages have since become the new norm of China’s economic policy. When growth started to slow in 2012, the authorities responded by rolling out more infrastructure projects to revive the economy, which has blotted China’s consolidated deficits every year since 2008. Although no official statistics exist on this, our best estimate is 8-10% fiscal deficits with the corresponding increase in public debt every year (fig. 2. above).

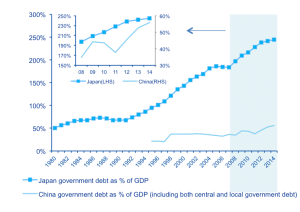

All in all, China’s public debt today is above 53% of GDP, according to the National Audit. This may look small by international standards, especially in the developed world, but the rate of debt growth is unmatched elsewhere, and is even higher than Japan with its recurrently large fiscal deficits.

On the corporate side, cheap money at home made it very – if not too – easy for companies to borrow. In fact, corporate debt has doubled as a percentage of GDP in the last 14 years. Beyond the stock of debt, its service is becoming an issue for corporations as the Chinese economy decelerates and their revenues are on the wane. Taking a very simple measure of stress in debt service, the ratio of EBITDA to interest expense has been below 1 for about one third of Chinese domestically-listed corporates, implying that their operating cash flow was insufficient to service their interest payments. This is especially the case for private ones.

*Continue reading at Bruegel.