Nick Malkoutzis via Macropolis | A Greek businessman, a Greek minister, a Greek opposition MP and a German official go to an economic conference. The German ends up being the only one that defends the Greek position. It may sound like a bad joke but it is a sad reality.

Following a panel discussion on debt and growth at the excellent Delphi Economic Forum last week, a Greek businessman in the audience pointed out to Economy Minister Dimitris Papadimitriou that it’s fine talking about growth but the reality is that the drawn-out review is eroding confidence and damaging the economy (an understandable argument that Monday’s Q4 2016 GDP data might back up). The entrepreneur placed the blame for the failure to conclude the review at the Greek coalition’s doorstep.

The first panellist to respond to the intervention was Philipp Steinberg, the director general at the Economy Ministry in Berlin. “It’s not just the Greek government’s fault,” said the German official before going on to explain the complexity of the current review, particularly in relation to the role of the International Monetary Fund.

Greek Economy Minister Dimitris Papadimitriou spoke next but simply to say he had nothing to add to his German colleague’s response.

He was followed by New Democracy MP, and ex-alternate finance minister, Christos Staikouras who was not satisfied with the explanation that several factors, not all of them rooted in Athens, had contributed to the review’s delay and he proceeded to list a number of areas in which he felt Greece had let the lenders’ down.

The brief exchange provided a telling insight into Greece’s fragile, self-denigrating frame of mind. After seven years of being pummelled by criticism, it has become difficult, even inconceivable, for many Greeks to believe that they, their country or their government are not exclusively responsible for the problems they face. There is a flipside to this, which involves some Greeks blaming everything on others but let’s lead that one aside for the time being.

Undoubtedly, the polarisation of Greece’s political system and public life – characteristics that predate the crisis but which have at times being exacerbated by it – play a role in this. There has been a distinct feeling since 2009 that those in opposition would like to see each government fall flat on its face even if the pain of that collapse would be felt, and paid for, by the whole country, setting its recovery hopes back significantly and, therefore, destroying the prospects of those waiting in the wings before they even come to power.

However, there is more to it than that. The low quality of Greece’s political elite and its subsequent inability to get to grips with the crisis, the scapegoating from some foreign politicians and journalists, sensationalism overpowering balance and genuine insight in the local media and the determination of many to fit events to their rigid ideological beliefs has created a dangerous mix. In this pernicious environment, Greeks have often lacked the knowledge and unvarnished facts they need to understand what is happening to them, while those pursuing their own agendas have preyed on these doubts to present themselves as having exclusive access to the single truth.

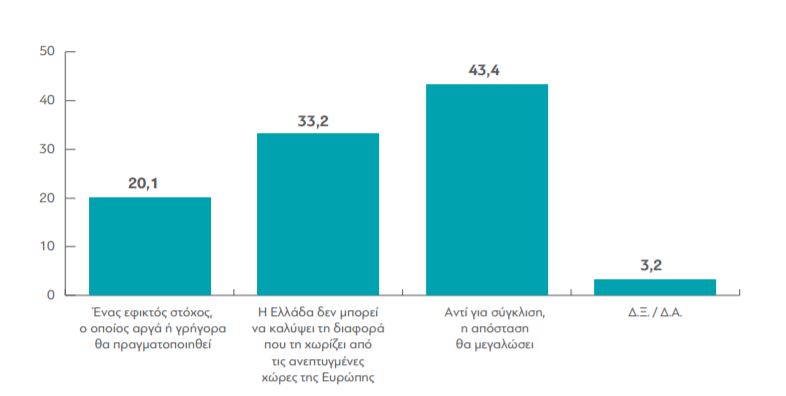

One of the consequences of this process is that it has drained the belief Greeks have in their own or their country’s abilities to contribute anything positive. The proportion of those who feel that Greece is a pariah, responsible only for making a mess of things and lagging behind others, has grown during the crisis. According to the latest poll by think-tank Dianeosis on “What Greeks Believe,” just 20.1 percent think that Greece will be able – sooner or later – to achieve actual convergence with the most developed countries in the eurozone.

In April 2015, the figure was 31.5 percent. According to the same survey, the proportion of Greeks who think they are not living in a modern country rose from 26.8 percent in April 2015 to 38.9 percent in December 2016.

The Delphi snapshot is living proof of the sense of guilt and inferiority that has overtaken much of Greece, right from the top. It was interesting, for instance, that Papadimitriou chose to say nothing in defence of his government, leaving this job to his colleague from Germany. The current coalition has much to be embarrassed about and Greece’s communication strategy at government level has been lamentable throughout the crisis, but the lack of fight from the economy minister suggests Athens does not have the will to explain that the review’s delay is not solely, even not primarily, its fault because it is certain nobody will listen or care anymore.

Also, although Greek business has been abused by the current government, as well as its predecessors, the entrepreneur’s expression of frustration with the government indicates he is not willing to countenance the possibility that the responsibility for the latest delay may lie beyond Athens.

The reaction of the New Democracy MP, meanwhile, also hints at the self-destructive streak that has been a characteristic of the crisis era in Greece. By singling out a range of issues on which he believes the government has been dragging its feet (exactly as his own administration was accused between 2012 and 2015), the lawmaker indicates he would rather embarrass his counterpart and give himself a boost than admit there is also culpability on the lenders’ side.

That leaves the German official to give a balanced take of the situation, admitting the complexity of getting the lenders and the Greek government on the same page and the sensitivity of some of the issues being discussed. This, after a presentation in which he accepted the difficulties the programme has caused, acknowledged the efforts that have been made in Greece but also highlighted where the country has fallen dreadfully short, particularly in terms of laying the groundwork for growth.

On the Greek side, the presence of mind, the rejection of partisanship, the knowledge and the belief needed to deliver this kind of assessment is absent. Sadly, the joke is on us.