*This article was originally published by Fair Observer

Peter Isackson | In a New York Times article that appeared just before this week’s interminable presidential cliff-hanger of an election, Lisa Lerer pondered how things might unfold after a Biden victory. She and the rest of the US punditry thought at the time that it might be decisive enough to define the future of the nation. Lerer cites Representative Pramila Jayapal’s speculation that Biden’s triumph could inaugurate an era of spectacular reform: “A White House victory would give Mr. Biden a mandate to push for more sweeping overhauls.”

As a member of the small group of progressives in the House of Representatives, Jayapal desperately wanted to promote the idea the Biden campaign hinted at months ago that would boldly step up to govern as a latter-day Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the president who changed American history and American capitalism with his New Deal in the 1930s. Jayapal supports the Green New Deal. The pundits had announced that the expected “blue wave” would reinforce the party’s majority in the House and give it control of the Senate. Whatever Biden ended up standing for, that reconfiguration of power implied a mandate for change.

A little more than a year ago, The Daily Devil’s Dictionary, offered its initial definition of “mandate” in a different context. Referring to events in Israel at the time, we defined the word in these terms: “Permission to play the role as a legitimate authority even when legitimacy has never been clearly established.”

Both today’s and last year’s definitions are valid, underlining the fact that vocabulary always derives its meaning from context. No dictionary definition can exhaust the full sense of what any item of vocabulary represents for real human beings. The very idea of a dictionary definition of any word should be seen as a myth. It may offer comfort to some parents and teachers, who can send children to a book they deem authoritative, but it is in contradiction with the reality of language.

What does that imply concerning the idea of a mandate in the days following this November’s historic US presidential election? In The Times article, Lisa Lerer went on to quote another Democratic politician, Henry Cuellar, a moderate from south Texas. Cuellar better reflects the rhetoric of the Biden campaign in its later stages and apparently expresses Lerer’s own sentiments: “If liberals had a mandate, then Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren would have won the primary. The mandate of the American public was to have somebody more to the center.”

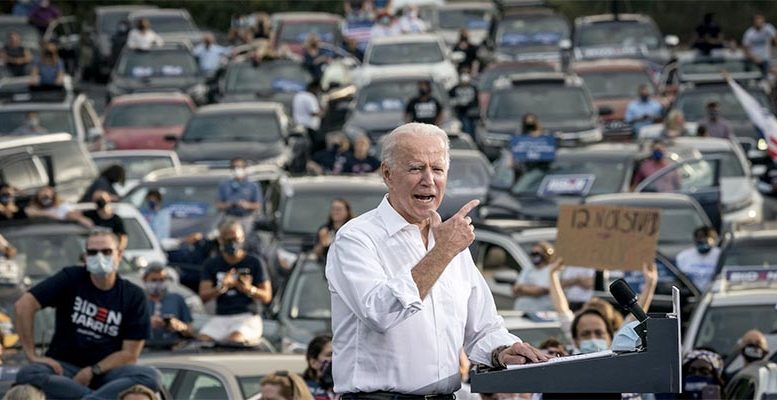

The Democratic Party under Biden proudly embraced the idea of pushing its agenda further to the center as the key to electoral success rather than wasting time on analyzing the needs of a nation in crisis and proposing remedies. In the later stages of the campaign, Biden insisted more strongly than ever on his credentials as a centrist by claiming, consistently with Cuellar’s remarks, that his greatest achievement in the primaries had been to defeat the socialist, Bernie Sanders.

That boast was something of an exaggeration. It wasn’t Biden who eliminated Sanders. In February, the “no malarkey” candidate was practically down and out, trailing in all the early primaries and penniless. That was until Barack Obama, working in the wings, stepped in to organize the defeat of Sanders, who had been riding a wave of momentum. Everything changed on the Monday before Super Tuesday.

As NBC News reported after the event, “there appears to be a quiet hand behind the rapid movement: former President Barack Obama.” He put pressure on the majority of remaining primary candidates to coalesce behind Biden. A month later, Glenn Thrush summed up the denouement of the primary fight in a New York Times article, noting how “with calibrated stealth, Obama has been considerably more engaged in the campaign’s denouement than has been previously revealed.”

Historical Note

After Super Tuesday, it was clear that Biden owed one to Obama, his former boss, who had not only ensured his survival but guaranteed his emergence as the “presumptive nominee,” a term that amused many commentators, who understood that though the primaries were not over, they had been “decided” by other people than the voters themselves. After overturning Sanders’ early momentum, could the idea take hold that Biden was a candidate with a mandate? As he hid in his basement during the lockdown and avoided the media, nobody could answer that question.

Obama may have had his own idea of that mandate. It would be the Democratic version of “Make America Great Again.” The former greatness to be aspired to this time could be defined as simply a return to the Obama years, but with one singular innovation: masks to fend off the coronavirus.

Beyond the triviality of hiding from contamination, the new Democratic agenda also meant turning the ship of state starboard to embrace the moderateness not just of mainstream Democrats and Obama loyalists, but also centrist Republicans. They called themselves anti-Trumpers and engineered The Lincoln Project.

The campaign’s essential and unique promise evolved into veering away from both Sanders populists on the left and Trump populists on the right. Instead of ideas for governing, it proposed a team of “trusted” political moderates, from Larry Summers to John Kasich, culled indifferently from the two dominant parties. When that is all a party can do, the very idea of trust becomes distorted and any hope of defining the terms of a mandate undermined.

The Democrats long ago stopped trusting the voters. That may be why voters have stopped trusting Democrats. Even Kamala Harris failed to earn any trust from the voters in the primaries, although she was initially touted as the ideal Democratic candidate. She was one of the first to drop out of the race for fear of being humiliated in the actual primaries. The early primaries actually did show a movement toward trust on the part of the voters: Masses of voters expressed their trust in Sanders. It wasn’t so much trust of the man as trust in his ability to fashion a program that could define a mandate for the next president, whoever that might be. That changed as soon as Obama stepped in to restore order.

In his article on Fair Observer yesterday, “Can America Restore Its Democracy?” John Feffer wrote: “Unlike 2008, the Democrats will be hard-pressed this time to claim an overwhelming popular mandate after such a close election.” Even after a landslide victory and the conquest of the Senate, it is far from certain that Biden would have understood that the voters had given him a mandate for anything more than imposing the wearing of masks in public.

The final irony is that, if confirmed, Biden will be the president to have culled the greatest number of votes in the history of the nation thanks to a record turnout of nearly 67% of eligible voters. That kind of enthusiasm to go out and vote — or, in times of pandemic, “stay in and vote” — should logically reflect an enthusiasm for a political program in times of crisis when serious change has become an absolute necessity. Not this time. Neither Trump nor Biden had anything to propose that could translate into a mandate to govern. Three days after the polls closed, we still don’t know who won in a contest between two candidates with nothing to offer. That tells us a lot about the state of US democracy today.

In an article in The Guardian, Columbia University Professor Adam Tooze assesses the obstacles in Biden’s path if he seeks to achieve anything Republican Senate majority leader might oppose. He concludes that “this election threatens to confirm and entrench the poisonous status quo.” In some sense, that makes Biden’s mandate easier. Like Obama, who quickly lost his congressional majorities, he will be able to say that it’s the Republicans who are preventing him from responding to the real needs of the people and a nation in crisis. And the status quo will carry on with business as usual.

*This article was originally published by Fair Observer.