“It appears to be the case that central banks have decided to help stock markets, with equities and credit doing remarkably well in spite of weak global growth,” said this week Hugo Anaya of JP Morgan Chase in Madrid.

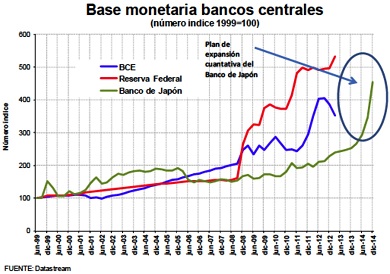

Anaya is right. The Bank of Japan has embarked in a huge expansion of the monetary base, and the Federal Reserve in the US announced soon after jobs data were published that it will continue printing money as well as its counterpart in the UK, buying their own government debt. But the most prudent of all, the European Central Bank, hasn’t been able to follow its counterparts yet.

Governor Mario Draghi has barely managed to cut the main interest rate down to 0.5 percent, playing in the same league as India, which has also lowered interest rates, Poland, Hungary and Russia,where analysts expect rates to fall during the next months. Meanwhile, according to JP Morgan Chase, ECB levels of liquidity excess are some €500 billion below those in previous interventions.

It isn’t hard to understand why critics of austerity and the ECB monetary policy are getting more restless every day. The link between less liquidity and worse economic figures looks clearly defined by the extreme timidity of the ECB and the fact that Germany last March joined France, Italy and Spain in the contraction zone of the services sector’s purchasing managers index–as the rest of the euro region, that is, recording less than 50 points.

Nevertheless, there is little hope about the ECB changing gear and direction. It will not meet the path of the other central banks in the developed economies any time soon. Jeroan Dijsselbloem, head of the Eurogroup, said Tuesday that austerity is the only way to reactivate the economy and public finances must be balanced, and Germany Finance minister Wolfang Schaeuble explained that fiscal consolidation is a previous step to reach sustainable growth. The numbers in the US and the UK tell a different story, though: unemployment and recession are much more tamed in both countries, and reforms more likely as a result.

Perhaps the problem in the European Union has more to do with rogue politicians than need of strict budget cuts. If so, Berlin and Brussels should speak up instead of imposing unattainable goals via mistaken strategies.

Be the first to comment on "ECB monetary policy runs in the opposite direction"