Private investors have long been permitted to invest in banks. The ratio of private equity investment in the Big Five state-owned banks is 5.29 percent. The figure for the 12 national joint-stock banks is 41 percent. That for the 144 city commercial banks is 54 percent, and for rural financial institutions it is 90 percent.

It would be untruthful to say China’s banking industry has been entirely owned and monopolized by the state.

So why did the government make it a point to restate that “private capital will be allowed to set up banks” in the document that summarizes the decisions of the third full meeting of the Communist Party’s 18th Central Committee?

First, it is because regulations were never clear in this respect. With the exception of China Minsheng Bank, the majority of private investors that now partially own a bank did so when the bank had a share ownership reform or through acquisitions and gradual increases of share holdings. It is a breakthrough that the policy now explicitly grants them the right to set up a bank.

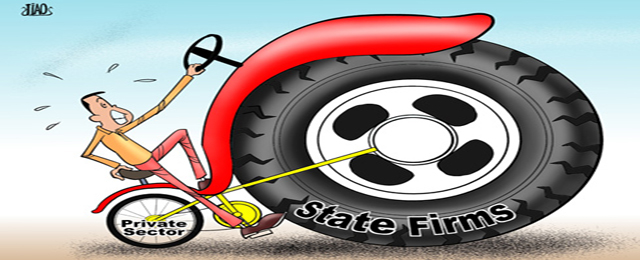

Also, because of the huge assets of the Big Five banks, private investors’ holdings in the country’s more than 3,000 banks account for only 10.68 percent of the total. This is obviously too low for an industry that should be open in nature. As long as we are pursuing a market economy, we should be providing a fair market environment and fair investment opportunities for all entities. When it comes to the entry barrier of the banking industry, private investors apparently should not be subject to extra restrictions.

Finally, with private banks becoming common, the market would have more vitality and large banks, especially those owned by the government, would come under more pressure to reform.

It is equally important that we realize the purpose of permitting private investors to set up banks. This matters for not only understanding the policy but also the decision-making of private investors themselves.

It has been shown that the ultimate purpose of dispelling ambiguity surrounding private investors setting up bank is to create a just market environment. The policy has been clear about this. Now the focus should be on how to avoid misinterpretation when the policy is implemented.

For example, some people may tend to understand the permission as opening the door for private capital to make more money faster. This oversimplified notion is worth our attention because setting up a bank means the investors must be prepared for risk. As for profitability, it is wrong to assume that there is a fortune to be made just by running in a bank.

In light of official statistics, the average rate of return on invested capital for industrial enterprises with annual sales of more than 20 million yuan is roughly on the same level with that for the banking industry. But the former’s average rate of return on assets is around 7 percent, whereas the latter’s is lower than 1.3 percent. The global average is about 1.13 percent. In the first nine months of this year, the former’s combined profits exceeded 4 trillion yuan, about 3.6 times that of the banking industry. Meanwhile, the banking industry’s assets were twice that of industrial enterprises.

This means the return on assets differs remarkably between banks and other industries, even though their returns on invested capital are roughly the same. We cannot fixate on a bank’s profit, which seems huge in absolute terms. It is important to also keep in mind that its assets are also huge.

The banking industry is a highly leveraged line of business where profit-making is extremely reliant on size. This means a bank must have a considerable amount of assets to generate high profits. A large amount of assets in return calls for more equity investment.

This raises some questions: How much private capital is prepared to be directed from the real economy to the financial industry? How should this migration be organized and paced? This is a question that needs to be answered by decision-makers both on the national and corporate levels.

Another issue that has aroused much attention is whether setting up more private banks can help small and family business finance and do so for cheaper. The answer to the first question is probably yes. The second has no clear answer.

The amount of outstanding loans to small and family businesses nationwide stands at 13.24 trillion yuan, or 27.8 percent of the total loans. A breakdown of the loans shows that the Big Five banks s account for 4.22 trillion yuan and the 12 joint-stock banks another 1.86 trillion yuan. The other two big lenders, city commercial banks and rural banks and credit cooperatives, lent out 1.98 and 3.19 trillion yuan, respectively.

This indicates that setting up more small banks would most definitely enhance the coverage of financial services and help ease the financing difficulty faced by many small enterprises.

The cost of loans is a different matter. As of October 30, the average lending interest rate of the Big Five banks was 6.35 percent. That of the 12 joint-stock banks was 6.45 percent and for city commercial banks’ it was 7.17 percent. Rural cooperative banks’ lending interest rates averaged 7.95 percent and small loan companies’ reached up to 15.96 percent.

This underscores the inverse correlation between a bank’s size and the interest rate it charges for its loans. The phenomenon is common around the world. So while it is desirable to have more private banks, whether they can lower the borrowing cost for companies is an open question.

Some private investors apparently were also hoping that a bank of their own means a stable source of loans. This is a grave misconception, above all because the law imposes strict restrictions on how banks can lend to a company and its related parties.

The law on commercial banks stipulates that the outstanding loans to a single borrower cannot exceed 10 percent of the bank’s total outstanding loans. It also says that “the credit line a bank extends to a single corporate group cannot exceed 15 percent of its net capital.”

There are other restrictions, such as “a bank cannot extend loans to its shareholders under more favorable terms than it does with other borrowers;” “banks cannot lend to related parties without collateral;” and they “cannot accept the ownership of its shares as pledge for loans.”

In addition, the banking regulator recently announced a policy that forbids a bank’s shareholders who effectively control its shares above a certain level from acting as a senior executive or a member of the board of directors.

These regulations in general put the investors of a bank under tough restrictions. It is not that all of them are rigid and cannot change. But many are already commonly practiced in developed countries. Some are even required by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision as precautions against insider trading and other financial hazards.

This is why it is important to thoroughly examine the policy about private capital setting up banks and understand it correctly. Authorities should keep this in mind when drafting implementation rules, and entrepreneurs should consider it when making investment decisions.

*Read the original article here.

**The author is a former president of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. The expressed views are his own and The Corner does not necessarily share them.

Be the first to comment on "What Letting Private Capital into Banking in China Really Means"