The time has come to say ‘enough!’ to those who brag about the reduction of the external deficit in Spain. Please, enough; it is meaningless. The truth is that it all depends on how you have achieved such correction, and in Spain it has been obtained after downsizing domestic demand.

Let me remind you of Okun’s law, which explains why an increase in investment triggers a drop in unemployment numbers. If we apply that link on to the external deficit, boasting about cutting it down would be like affirming that buying foreign productive capital goods and machinery must be the wrong thing to do. Of course, it isn’t. The Spanish outrageous unemployment levels have been caused precisely because investment has fallen, not because households save more.

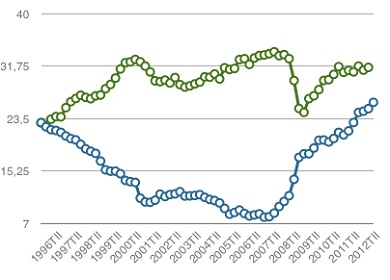

Let’s look into the chart, now. It turns out that high imports per GDP (the green line) are good to fight against unemployment: the blue line of joblessness descends when imports grow because there is a high domestic demand for capital goods that generate employment.

Spain tends to be one of those countries with external deficit as it is in need of capital goods. And this is all right if it’s financed with, say, direct investments. In that case, Spain could keep its deficit for a decade if needed. When this deficit vanishes because financing disappears, the consequences for the economy are depressing.

Our chart clearly shows the trouble we are talking about: since 2008, imports have gone up again, but closely followed by unemployment–which has these days reached a staggering 26 percent rate. This is dreadful. And it tells us that the adjustment process that Spain suffers has completely gone in the wrong direction.

When the Spanish economy returns to solid growth territory and sparks job creation, its external deficit will come up once more. Who will dare to say then that it is a bad sign? The Brussels plan is suffocating Spain’s economy.

Be the first to comment on "Who cares about Spain’s external deficit?"