Nick Malkoutzis via Macropolis | There couldn’t have been a more fitting end to the year in Greece than the Ferris Wheel fiasco in Athens’s Syntagma Square. It was the first year the city centre’s Christmas and New Year’s celebrations were to include this attraction. It went up amid much fanfare, only to come down a few days later as the structure did not have the necessary security certificates.

The unrequited hope reflected in the pods being removed from the Ferris Wheel before anyone could step into them is very much the story of 2016 for Greece. It was cast as a watershed 12 months, when we were meant to leave the worst of the crisis behind us and start to look to a brighter and more stable future.

Instead, it was a year of more social upheaval as farmers, engineers and lawyers protested against changes to their social security and the rest of the population had to absorb the burden of another 3 percent of GDP in new measures needed to conclude the first programme review. This was only enough to secure a loose commitment to debt relief from the eurozone. The vagueness of this pledge came back to bite Greece on December 5, when (in the absence of the second review being wrapped up) the Eurogroup agreed to implement very limited short-term debt relief measures (reducing Greek debt by 20 percentage points between now and 2060) and not to discuss medium- or long-term steps to bring down the country’s debt pile from around 180 percent of GDP until the current programme has been completed in 2018.

Small mercies

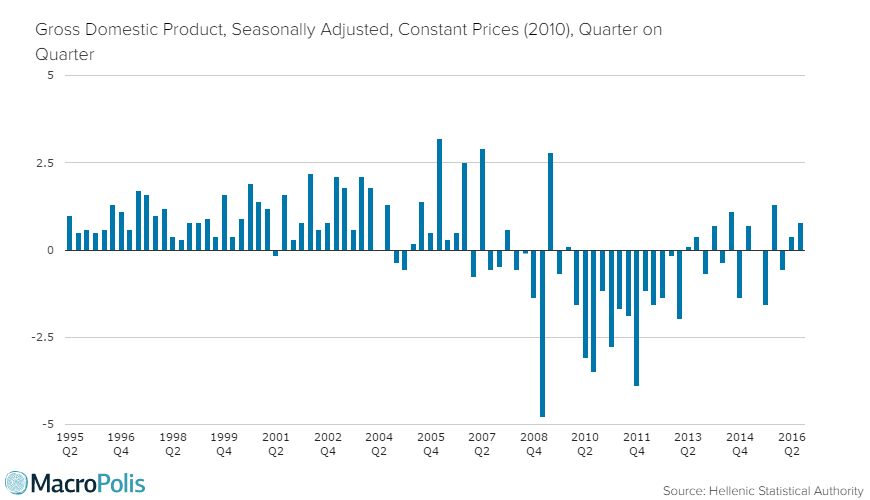

There were some small mercies to be thankful for in 2016. For starters, Greece went through a whole year without having elections, although this run may be broken in the coming months if the SYRIZA-Independent Greeks government is unable to reach an agreement with the lenders on the second review. We also witnessed the bottoming out of the recession, with seasonally adjusted GDP rising quarter-on-quarter in Q2 and Q3, although the recovery remains fragile and extremely vulnerable to the outcome of negotiations between Athens and the institutions.

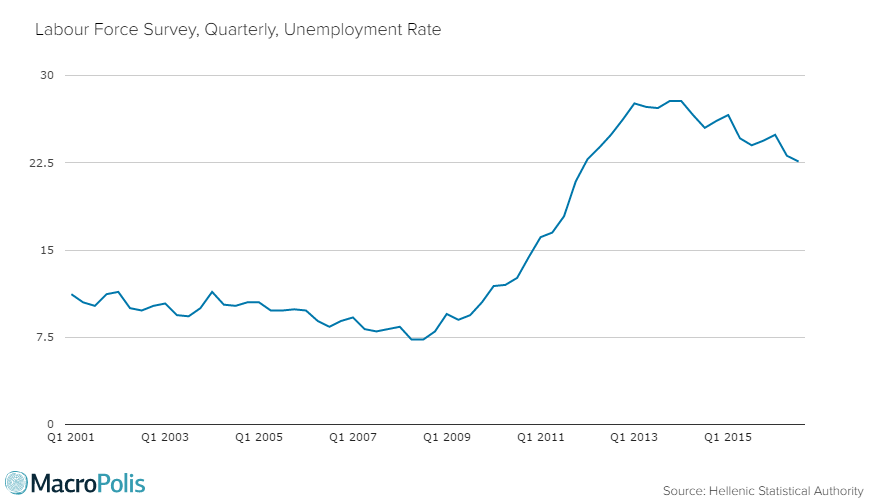

Unemployment has also edged down, dropping to 22.6 percent in Q3, which is the lowest since 2011 but still alarmingly high. Equally, the high number of long-term unemployed (806,300 people had been without a job for at least 12 months in Q3) remains a pressing economic and social concern.

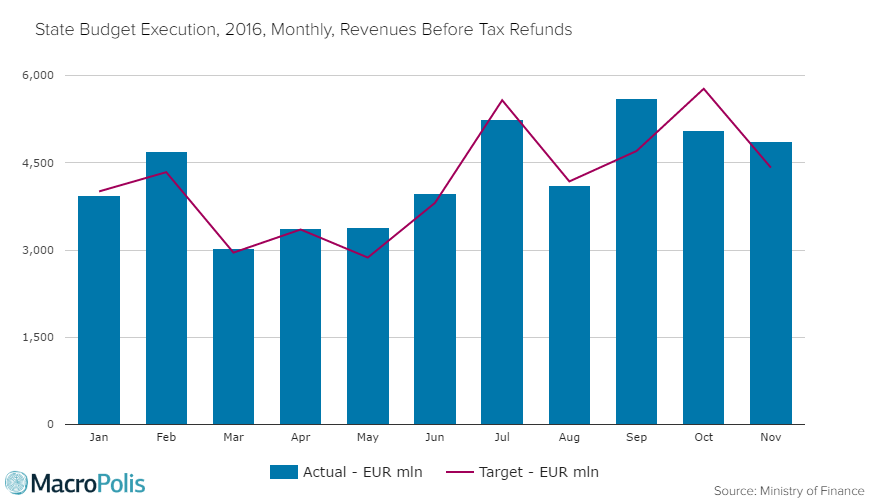

On the fiscal front, revenues have provided a positive surprise. At the end of November, they were 1.28 billion euros above their target, ensuring that Greece is on track to beat its primary surplus goal of 0.5 percent of GDP for the year. The government puts this down to better tax collection but it has been helped by the fact that – because of the imposition of capital controls last year – there has been a double-digit increase in the use of debit and credit cards and a sharp rise (18 percent in Q1 and 15.9 percent in Q2) in VAT collectability in 2016.

Worrying fundamentals

Many of the Greek economy’s fundamentals remain worrying, though. The tax burden, which is 2.5 percentage points above the OECD average, is far too high for a country struggling to find a path to economic recovery. Liquidity remains out of reach as the credit contraction that began in 2011 continued unabated this year, with local banks engaging in further deleveraging of more than 3 billion euros. Meanwhile, lenders’ non-performing exposure continued to rise, reaching 45.2 percent in September. Unsurprisingly, debts to the state also increased, reaching 92.3 billion euros in October. Greece’s current account surplus up to the end of October was down by 42.6 percent compared to last year as exports fell by 2.7 percent during the first 10 months of the year.

Along with this economic weakness comes social fragility. According to Eurofound’s annual survey, 38 percent of Greek workers say their household made ends meet “with great difficulty”, while the same percentage said it did “with some difficulty”. This is more than double the EU average. Greece continues to rank as the worst performer in the EU in terms of social justice, according to the Bertelsmann Foundation’s latest report. Eurostat data shows that Greece has the second highest share (26.1 percent) in the EU of young people aged 20-24 who are neither in employment nor in education or training (NEETs).

It is no surprise, therefore, that an MRB opinion poll published a few days ago suggested that 71.1 percent of Greeks aged 18 to 24 and 60.3 percent aged 25 to 34 would leave the country if they had the chance. According to research by Endeavor Greece, some 350,000 Greeks have left the country during the course of the course and are currently producing around 13 billion euros a year in GDP and another 9 billion euros in taxes abroad.

Expected turnaround

Maybe these wounds will start to heal next year, when the government expects the economy to grow by 2.7 percent and living, working and investing in Greece might seem a more enticing prospect. It is difficult, though, to be anything other than cautious about the prospects of such a turnaround. Firstly, there will have to be a dramatic improvement in several sectors of the economy for this kind of growth to be achieved. According to the Bank of Greece (which sees a recovery of 2.5 percent), private consumption will have to increase by 1.3 percent, investment must climb by 10.2 percent and exports will need to experience a 3.2 percent boost.

The other factor that fuels doubt is if or when the current review will be completed. The Greek coalition is targeting the January 26 Eurogroup to wrap up the negotiations but it had also previously aimed to conclude the talks by the December 5 meeting of eurozone finance ministers. The issues remaining on the table, particularly labour reform, the fiscal gap for 2018 and the measures for after 2018, are politically sensitive. If the creditors continue to insist on prolonged or further flexibility in the Greek labour market and the upfront legislation of more than 2 percentage points in fiscal measures to be implemented from 2019 onwards, it is very likely this government will not be able to accept such conditions. Instead, it will probably opt to hand over the problem to someone else via snap elections that SYRIZA seems certain to lose.

The question will then arise whether anybody else can take the reins of power in Greece and agree to measures that mean pension spending, which has already been slashed by around 30 percent since the start of the crisis, being reduced by another 20 percent and the tax-free threshold coming down from 8,500 to 5,000 euros. In short, the failure to conclude the review in the coming weeks will likely lead to another period of prolonged uncertainty in Greece, which has been so enfeebled by the constant incertitude of the crisis.

In many ways, Greece finds itself back where it was in December 2014, when the prime minister at the time, Antonis Samaras, did not want to use up the minimal political capital he had left to meet the creditors’ demands. The snap elections that followed gave birth to the most intense period of uncertainty in the Greek crisis.

Perhaps they should have kept the Ferris Wheel at Syntagma Square after all. Without its pods it looks very much like a giant hamster wheel. It would have been the most appropriate symbol for Greece’s predicament.