There are myriad indications that the troika-led fiscal policy mix in Greece has had an element of futility but often factors such as political instability, social tension or lack of programme ‘ownership’ are cited to justify the reasons that the prescription does not have the desired effect.

Probably the loudest signal regarding policy shortcomings was sent out in 2014. Unfortunately, it went unnoticed in the sensationalism of the SYRIZA win in the January 2015 elections, and the six months of colourful characters and cliff-hanger negotiations that ensued.

The prevalent narrative is that 2014 was a good year for Greece. The economy appeared to be bottoming out and in the run up to the European Parliament elections of June 2014 the country was hailed by officials across the eurozone as a success story. It had managed to tap international markets for the first time since 2010 with two small issues of 3- and 5-year bonds and, after years of recession, the first sign of growth was recorded in the third quarter.

It was all supposed to be going so well that the government led by New Democracy’s Antonis Samaras openly claimed that it would seek a clean exit from the bailout at the end of that year. Finance Minister Gikas Hardouvelis went as far as suggesting in September 2014 that Greece could find in the markets better rates than those charged by the IMF, justifying the government plan to quit way ahead of time the International Monetary Fund part of the programme that was due to expire in the first quarter of 2016.

Yet, the budget execution of that year missed the primary surplus target by miles. The troika’s programme called for a primary surplus of 1.5 percent of GDP, which translates into 2.75 billion euros. That was supposed to be the first step toFMIwards the massive surplus of 4.5 percent of GDP that was envisaged from 2016 onwards as a prerequisite for debt sustainability. In fact, ELSTAT reaffirmed last week that the primary figure did not exceed 0.4 percent, recording an upwards-revised surplus of 705 million euros. This meant the target was missed by more than 2 billion euros.

Taxes underperformed by 1.3 billion euros, direct tax revenues missed the target by 932 million, indirect taxes missed by almost half a billion, led by lower than forecasted transaction taxes, notably VAT. The indirect tax intake was even lower than the previous year’s.

At the same time, the amassing of unpaid taxes to the state continued unabated. This added another 13.8 billion euros of new tax debt to the existing stock of unpaid obligations.

Under normal circumstances those in charge of the design of Greece’s programme should have stopped to take stock and ask why even with a prime minister that was more or less playing ball and finance ministers that were not sporting unorthodox attire or economic views, the Greek economy failed to meet the demanding fiscal targets. No one cared to look into the implications of that miss and most critically what it meant for future implementation, which was calling for even stricter fiscal goals.

Although one outcome of last year’s negotiations was that the goal for the primary surplus in 2018 was lowered by 1 point to 3.5 percent, Greece and its lenders again find themselves – just half a year after they agreed the third programme – stuck in talks to close a fiscal gap between now and 2018 that ranges from as high as over 8 billion euros (according to the IMF) to a more moderate 5.5 billion (favoured by the European Commission).

When the IMF’s Managing Director Christine Lagarde commented recently that if Greece were to reach the 3.5 percent of GDP target it would require a “heroic effort” by the Greeks this is what she must have had in mind.

Starting point

The Sisyphean task starts as far back as the end of 2009, when George Papandreou took office and it became obvious that his predecessor, Kostas Karamanlis, had been hiding for months the true extent of Greece’s fiscal problems, assisted by the European side and the Commission that turned a blind eye in the obvious derailment early in that year.

At that time the deficit was estimated at 12.7 percent. Contrary to the popular belief that Papandreou’s government was too late to act, it submitted a budget that intended to cut the deficit by 3.6 percentage points, or 8.4 billion euros. 1.8 percent of GDP would come from revenue measures and the remainder from expenditure cuts including hospital and defence spending. (Page 63, in Greek)

Although it was becoming obvious that Europe would need a concerted effort to deal with the impeding debt crisis, with Greece being the immediate problem, the approach that suited domestic political considerations by member states led by Merkel in Germany was that more austerity would need to be applied to re-gain the confidence of the markets. Having little credibility after Karamanlis fake statistics and no other choice, Greece did as it was told and tightened further.

In mid-January 2010, it submitted an updated Stability and Growth Pact, that included a total of roughly 9.4 billion euros of savings and revenue measures, outlined in Annex C here, which would reduce the deficit to 8.7 percent of GDP.

A European Council decision in mid-February asked Greece to deliver even more fiscal discipline. Under the false impression that more belt tightening would appease markets, by mid-March Athens submitted another package worth 2 percent of GDP, equally split between revenues and cuts, 2.4 billion euros on each side. (Page 10)

Papandreou’s government had committed to 14.4 billion euros of fiscal consolidation and it was not even the end of the first quarter of the year.

When Greece signed the first programme with the eurozone and the IMF in May 2010, it committed to applying an additional 2.4 percent of GDP of measures by the end of the year on top the existing interventions. (Table 5). That brings the total fiscal effort of 2010 to a phenomenal 20.1 billion euros, split between 9.9 billion in revenue measures and 10.2 billion euros in spending cuts. This dispels another popular misconception that the austerity policies adopted by the government were mostly geared toward raising taxes.

In the meantime, the deficit of 2009 had been twice revised upwards by Eurostat to 15.4 percent by November, pushing up the starting point of Greece’s fiscal effort by an extra 3 percent of GDP.

Based on the memorandum with the troika, Greece tabled a 2011 budget that had an additional 9.2 billion in measures, this time mostly depending on the revenue side, with 6.6 billion euros coming from various tax increases and 2.6 from spending cuts. (Table 2.3).

Following the revision of the 2009 deficit, the almost 20-billion-euro austerity dose of 2010, reduced the deficit to 9.4 percent of GDP. The initial plan was that the 9 billion euros of austerity in 2011 would reduce the deficit by 4.9 billion euros to 17 billion. 15.3 billion of that (or 6.7 percent) amount was interest payments, up from 14.2 billion in 2010. Excluding the interest obligations, Greece was hoping to reach a primary deficit of just 1.7 billion euros. (Table 2.2).

Greece’s programme started going off track early in 2011 when it became apparent that the volume and intensity of the austerity was stifling the economy and all assumptions were going out of the window.

Off track

But 2010 set the tempo and the policy of “stacking” more measures was established. In June 2011 and then in October of the same year, Greece committed to an additional 7.5 billion euros of further austerity (Table 9). Greece found itself running just to remain in the same spot in 2011. The Commission described the volume of austerity as follows:

“[…], most of the measures effectively served to counteract the upward drift in expenditure and downward pressure on revenue. The former mainly results from an automatic trend increase in several large spending components such as pensions and healthcare; the latter mainly stems from the recession but possibly also a deterioration in tax compliance.”

The measures in 2011 reached a total of almost 17 billion euros, which combined with the 20 billion of 2010 brought the total bill in the first two years of adjustment to over 37 billion euros of measures, which were repeatedly pilled on to counterbalance the cyclical effect of an economy that was collapsing under the stifling intensity of the prescribed austerity and the social and political tensions that it was fanning.

Greece committed to another round of heavy fiscal lifting in 2012 with 12.4 billion, 6 billion in cuts and 6.4 billion in revenues (Table 2.2, in Greek).

This meant that in three years, Greece implemented close to 40 billion euros of austerity, to correct around 20 billion euros in its primary deficit and losing roughly 30 billion of its economy along the way.

The underlying factor behind this ongoing misery is the debt that ELSTAT last week confirmed as standing at 311.5 billion euros at the end of 2015, roughly 1.8 times the size of the Greek economy.

Aside from the fact that nobody would be willing to lend to it Greece, simply cannot add any more to this pile. The general concept is that the country should reach the point that will generate enough surpluses to fully cover its interest payments and then a bit more on top so it starts paying back debt, eventually bringing it down.

As much as it is true that there have been a number of interventions over the years that have pushed debt maturities into the future and have brought servicing costs down from pre-crisis levels, when Greece was paying over 6 percent of GDP in interest, it remains unrealistic to expect the Greek economy to generate primary surpluses in the volume of 3.5 percent of GDP when it has implemented since 2010 a combination of tax increases and spending cuts that exceed 30 percent of GDP just to bring the books in balance.

The IMF itself has questioned numerous times the feasibility of Greece reaching and maintaining surpluses of that magnitude. The IMF’s Poul Thomsen left little room for interpretation when he said during a press conference at the Fund’s spring meetings that Greece is a country with huge unemployment that will remain in double digits for several decades hence it is not credible to assume that it will be able to maintain the surplus that the Europeans (led by Germany) are demanding. “That’s a lot of, if you want, austerity,” he said in plain terms.

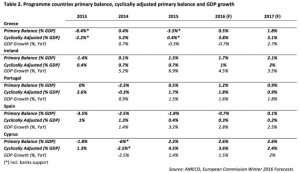

To put this in some context, according to the European Commission’s macroeconomic database (AMECO), Ireland left its programme at the end of 2013 with a primary deficit of -1.4 percent of GDP. It posted a surplus of 1.5 percent of GDP in 2015 when its economy grew by a phenomenal 6.9 percent. Its 2016 primary surplus is seen at 1.7 percent of GDP with the economy growing by 4.5 percent

On a cyclically adjusted basis, which fully captures the impact of the economic devastation, Greece has from 2013 achieved a significant primary surplus when you strip out the one-off spending on bank recapitalisations. The figures demonstrate how much fiscal effort Greece has delivered in a hugely challenging economic environment. (Forecasts).

Any discussion about Greece’s future and fiscal health should include a sensible goal for primary surplus that will allow the economy to breathe after six years of fiscal retrenchment. Equally importantly, it should remove the uncertainty that comes with each review as it is forced to reach fiscally unattainable heights.

Otherwise, Greece will yet again be a case where people are repeating the same action while expecting a different outcome.

*Image: Flickr /Jack Zalium