Given the significant slack in the economy and the price adjustment at play in peripheral countries, we believe inflation is set to remain weak for a long period of time, adding to the weakness in nominal GDP. Therefore, debt dynamics look complicated despite fiscal consolidation and the ECB will likely act more in 2014 to alleviate the pressure stemming from weak nominal growth.

Last week, GDP data showed a 0.1% increase in the euro area for Q3, which confirmed that the single currency union has been growing for the second consecutive quarter, therefore putting an end to six quarters of recession. However, the rebound has been very subdued so far and remains fragile, in line with our expectation.

Although Germany is still the euro area’s main growth driver, growth was somewhat disappointing at only +0.3% q/q, while both France and Italy contracted Q3 by 0.1% q/q, versus our expectations of flat readings. By contrast, Spain and the Netherlands were lifted out of recession, but posted only a 0.1% q/q increase. Only Portugal and Greece surprised positively, growing for a second quarter in a row: +0.2% q/q and +0.3% q/q, respectively.

The expenditure breakdown has not been given for all countries yet, but according to the information released and according to our own estimate, a build-up in inventories was probably offset by a negative contribution from net trade, while domestic demand was broadly flat.

We look for a modest rise in Q4 13 as global demand recovers and drives exports higher; we believe that the economy should gather speed next year. However, some significant headwinds persist and are likely to remain a drag on activity: fiscal policy is still restrictive and will likely remain so in a foreseeable future.

The private debt overhang has hardly started to decline and should exert a drag on domestic demand for several quarters in most of member states; competitiveness adjustments, although positive for the future evolution of exports, are negative for domestic demand in the near term; last but not least, credit conditions remain tight in many peripheral countries as financial fragmentation persists, and the upcoming comprehensive assessment of bank balance sheets by the ECB might temporarily weigh on the distribution of credit by banks.

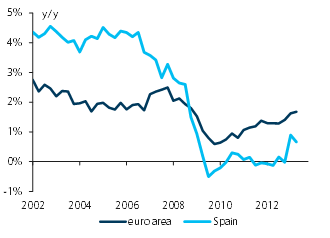

In this subdued growth environment, inflation has dropped to a low 0.7% y/y in October from 2.6% y/y during the summer of 2012. Although a significant contribution to this decline came from energy, food and taxes, low inflation also reflects some weakness in goods and services prices stemming from the significant slack in the economy, as well as the price adjustment at play in peripheral countries (internal devaluation).

Price pressure as measured by the annual increase in the GDP deflator has actually been running well below 2% since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008 (see Figure 1).

In a country such as Spain, where the price adjustment has been particularly marked, the GDP deflator has been roughly unchanged since the beginning of 2010. Although the ECB notes that inflation expectations for the medium term remain well anchored, Mario Draghi acknowledged at the November press conference that inflation was likely to remain weak and well below the ECB’s reference value of 2% for a very long time.

In a country such as Spain, where the price adjustment has been particularly marked, the GDP deflator has been roughly unchanged since the beginning of 2010. Although the ECB notes that inflation expectations for the medium term remain well anchored, Mario Draghi acknowledged at the November press conference that inflation was likely to remain weak and well below the ECB’s reference value of 2% for a very long time.

Given that growth is likely to remain very subdued, that global inflation weakness is likely to persist and that price adjustment in peripheral countries still has a long way to go, inflation will likely undershoot the target for another couple of years.

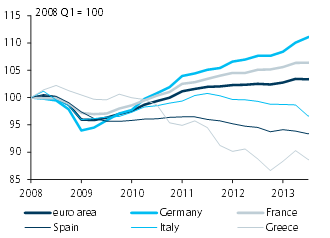

Subdued growth and weak price pressure are putting debt sustainability at risk given that nominal interest rates are constrained by the zero bound. In several euro area countries, the public debt to GDP ratio will continue to increase at least until 2015, despite a significant reduction in the deficit, owing to the weakness of the denominator (nominal GDP is still below its pre-2008 crisis peak in several countries, see Figure 2).

Therefore, the ECB will have to keep monetary policy very easy for several years. We believe the purpose of the forward guidance introduced in July was to convince financial markets that rates will remain close to zero for an extended period of time, such that this translates into low and stable yields on sovereign bonds, a condition deemed necessary to safeguard debt sustainability and therefore, financial stability.

Therefore, the ECB will have to keep monetary policy very easy for several years. We believe the purpose of the forward guidance introduced in July was to convince financial markets that rates will remain close to zero for an extended period of time, such that this translates into low and stable yields on sovereign bonds, a condition deemed necessary to safeguard debt sustainability and therefore, financial stability.

The rate cut decided two weeks ago was clearly aimed at reducing the downside risk for inflation (and then indirectly the risk of debt deflation) and we believe that further action will be necessary in 2014. Another cut in official interest rates (including in the deposit rate) is not excluded, but we think the ECB will likely use unconventional tools to boost the quantity of money in circulation. A ‘conditional LTRO’, a funding for lending scheme, or even a securities purchase programme will likely be on the agenda in 2014.

Be the first to comment on "Euro area: Weak growth and low inflation put debt sustainability at risk"