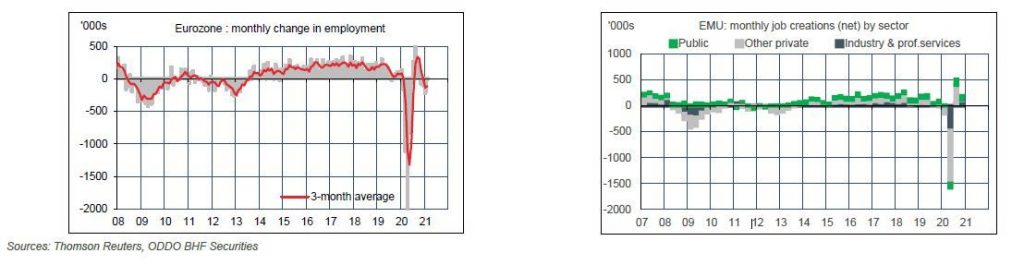

Bruno Cavalier (Oddo BHF) | The impact on employment has been largely cushioned by partial activity mechanisms.

The reduction in the number of jobs during the lockdown in the spring of 2020 was much deeper than during the Great Recession of 2008-2009. But in the context of falling activity, the adjustment seems almost moderate. The partial activity mechanisms adopted in all countries served as a buffer. Without them, the direct negative impact on incomes and the indirect negative impact on consumer confidence would have been magnified.

The return to a normal operation of the labour market is a long-term perspective. Firstly, employment support mechanisms have softened the effects of the shock, but they are not a substitute for permanent adjustments. As the crisis approaches its end, it is inevitable that business failures and, by extension, job losses will increase. Secondly, the crisis has changed work habits and the structure of demand, in particular for transport and consumer services. Some of these changes are reversible, others are not. It is too early to predict the final effect on the volume of employment and worker productivity.

Sector inequalities make a full normalisation unlikely

At first glance, the “scar” on total employment looks set to be less deep than after the 2008 financial crisis. However, at the sectorial level, the shock may turn out to be deeper or longer lasting. One example is tourism, one of the sectors most affected by the pandemic and one of the most labour-intensive.

These sectorial divergences may have consequences for the pace of recovery in European countries depending on their degree of exposure to tourism.