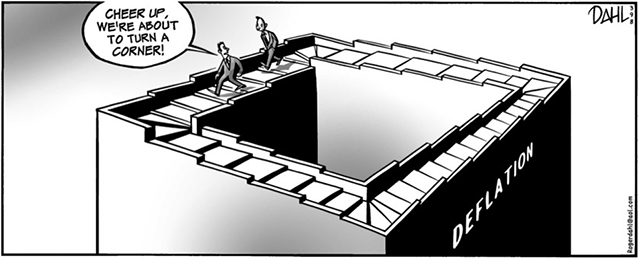

In May, the eurozone’s price inflation reached new a low, at 0.5 percent. This is alarmingly close to deflation, which many economists have warned against for some time. Call it the Japanese economic illness. The European Central Bank (ECB) fears this scenario. At its latest board meeting, the ECB took further steps in fighting deflation. One step was historic and the other was a 400 billion euro financing support package, something that is worth following in China.

Let’s take the historic step first. The ECB lowered its key lending rate from 0.25 percent to 0.15 percent and the deposit rate to minus 0.10 percent. That the lending rate was lowered marginally will not change anything. Consumers and corporations will, of course, not see the marginally lower interest rate as an incentive to increase spending or investments. But operating with negative deposit rates is historic because the ECB is the first central bank among the world’s large economies to do so. Not even Bank of Japan has done this in its deflation fight. The introduction of negative deposit rates has been used by two other European central banks lately, namely those in Denmark and Switzerland. The purpose for both was to reduce to currency inflows from foreign investors. Without any doubt the ECB would like the euro to drift lower as well. The open question is whether the punishment from the slightly negative interest rate will be enough for investors to leave the euro. In Denmark and Switzerland, it took some of the upward pressure away from their currencies. I do not expect a steep drop in the euro exchange right now, but it fits into our overall expectation that the euro will lose another 7 percent against the U. S. dollar and the yuan this year. A fast sell-off in the euro will only be caused by surprisingly negative economic data from the eurozone.

I turn my attention to another action by the ECB. The headache for the central bank since the financial crisis started has been to get cheap liquidity passed on to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It is a problem facing countries around the world because large companies with a good credit can borrow, but SMEs have difficulties finding financing.

As a solution, the ECB introduced a lending program with the rather bureaucratic name “targeted long-term refinancing operations,” or TLTRO. The 400 billion euro financing package is aimed at SMEs within the eurozone. The idea is not quite wrong. Because all SMEs around the world have difficulties getting financing, then the eurozone SMEs could gain a global advantage through this move. The question is whether the transition of credit from the central bank to SMEs will happen. In other countries, it has proven to be more difficult than expected because the channels are the existing banks. Many countries run some institutions targeting particular financing, but it is still done in a banking way.

The ECB will release more information about the detailed conditions that might give a brighter picture. So far, we know that in the first tranche eurozone banks can borrow up to 7 percent of the value of their loans made to the corporate sector as of April 30. Later on there will be further tranches based on the new lending from now and until then. But the first hurdle is that the banks do not even have to lend the money to the SMEs. In two years, the ECB will control where the funds go. If the bank did not forward the funds to the corporate sector, the banks will have to return the money. This means that the banks for the next two years can place the capital in government bonds and earn the higher interest rate.

The funds need to be repaid in 2018. This means that the financing period is effectively less than four years, which is a short duration for corporations. Further, it is unclear how the renewal of existing credits is counted. If a current credit facility matures but is re-installed under the new TLTRO program it seems to count as a new facility. But worst of all, it is just liquidity from the ECB and not risk-sharing. The total amount under the TLTRO program that will be allocated toward debt-troubled countries in the eurozone is 160 billion euros. It is a significant amount for the area, but many banks in these countries need to reduce their balance sheets due to a bad loan portfolio. They would only be able to channel the credit to the SME sector if the ECB took the credit risk as well.

Right now, it seems too difficult to be optimistic about the project. Of course some new lending will find their way to SMEs, but to talk about a boost is not in the cards right now. From a Chinese perspective, the good part is that eurozone SMEs will presumably continue to face scarce financing as well. Should I be wrong in my assumptions, then it means more growth within the eurozone SME sector. This will probably occur within the existing business sectors, i.e., not new-generation sectors. To continue this wishful thinking, then investing in new machinery might be interesting for some eurozone companies. Germany is the leader in this field, but China has improved seriously the past years. The question is whether Chinese companies can beat the traditional strong Italian companies within this field. I would expect this to be the case. But it is unfortunately not my main scenario, which is that the ECB will continue to fight against very low inflation and growth.

*Peter Lundgreen is the CEO and founder of Lundgreen’s Capital, an investment consulting and advisory company

Be the first to comment on "Europe’s fight against deflation"