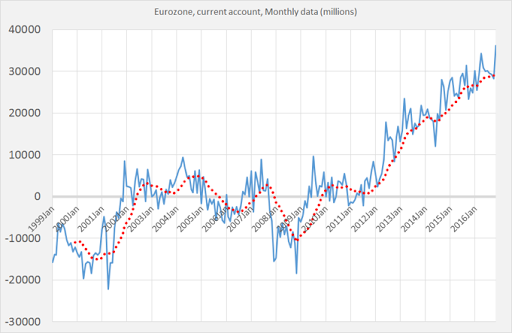

The Eurozone has an abundant external surplus, as can be seen in the graphic:

3 billion euros, or in other words, 3.1% of the region’s GDP. It doesn’t look like an excessive figure, but it looks as if it’s unstoppable. A large part of this excess is down to Germany, which has reached the incredible figure of 300 billion euros, or 9% of GDP. Both surpluses are the result of the fact that the euro is obviously undervalued which, at the same time, is due to Draghi’s monetary policy of Quantitative Easing. German Finance Minister Schauble has complained about this in response to Peter Navarro, Trump’s foreign trade adviser, when he accuses Germany, China and Japan of being disloyal by forcing an exaggerated competitiveness with its their exchange rate.

That said, Germany has no power over the euro. Furthermore, it has always said that it didn’t like Draghi’s policy, although it accepted it as necessary for the other countries in the euro. It blames Draghi for the surplus, but that’s also not true: Germany could implement a policy of public investment which will increase demand and also boost demand in the region.

In any event, this “German distortion” – and European-, will provoke actions from the US which will not help solve the problem. It would be a good thing if the US put diplomatic pressure on the Germans to increase their internal spending. But we already know that Trump shoots first and the consequences are seen later.

Both Germany and the Eurozone need to increase their domestic spending. Perhaps if Germany did it, it would be a driver for other countries with a surplus. But we should not expect anything from here. Germany has been repeatedly censured by the Commission for its excessive external surplus, which in line with internal regulations, should not be higher than 3%. But Germany turns a deaf ear. That it is its fault does not enter its economic dogma. What Germany says is that other countries should imitate it, which is an aberration. If the other countries in the Eurozone imitated it, the economic contraction would be tremendous. We would all spend less on the others, which would mean everyone’s production would contract. Germany’s external trade figures are an insult for the EU and the euro. It doesn’t look like the US would be too unhappy about getting rid of the single currency with the help of Le Pen and others, with its neo-mercantile view, fuelled by Germany’s mercantilism. This is the typical situation which Keynes feared: countries attacking each other in a trade war in which everyone is a loser. For Keynes, an imbalance between two countries is the responsability of those two countries, not just of the one with the shortfall. So both need to take action. One way is to have a free exchange rate which acts as a counterweight. Another way, if a decision is made to have a fixed exchange rate between the two, is to agree compensating policies – expansionary in the country with a surplus, contractive in the one with the shortfall – if relations are normal. If they decide to have a fixed exchange rate, it’s because there are advantages and the inconveniences can be rectified. We can see that this does not apply in the Eurozone.