Thus, some reflections about the state of play of the country’s economic prospects are warranted. A mixed picture is emerging, moving between positive sentiment indicators and higher car sales numbers being counterbalanced by news about sliding land prices in the Attica region and a continuous decline in construction activity.

The emerging economic stabilisation is primarily the result of a very successful tourism season in 2013 and this year. In 2013 more than 17.5 million tourists visited Greece, numbers not seen since Athens staged the summer Olympics in 2004. Tourism arrivals in 2014 are on course to surpass the threshold of 20 million, according to the Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises (SETE). Tourism now accounts for about a fifth of the country’s annual gross domestic product.

The other sector fuelling the recovery prospects is international demand for container shipping, of which Greece is a major provider. Greek companies own 16.1 percent of the world’s total merchant fleet, making it the largest in the world. The Greek shipping industry is a key factor in the calculation of the country’s annual GDP, and it is expected that in 2014 it will account for approximately five percent.[1]

But this emerging stabilisation from a low point of departure is still too frail and uneven across other sectors of the real economy and has yet to reach the centre of Greek society. While foreign tourist arrivals are booming, private domestic demand remains weak. Citizens becoming increasingly frugal despite declining consumer price inflation are a reflection of falling real earnings. Holding back on private household spending also mirrors the dramatic state of the Greek labour market.

The positive quarterly economic data from Greece should not lend itself to any triumphalism. German GDP grew by 0.1 per cent and that of France’s by 0.3 per cent while Italy remains in recession. If these developments in the euro zone are interpreted as an ‘upside surprise’ one can get a pretty good idea of the parlous state of the euro-area economy.

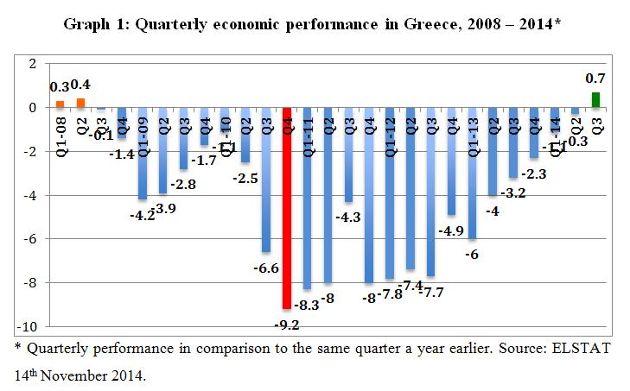

But considering where Greece is coming from after a record 24 consecutive quarters of negative growth the sense of relief among policy makers in Athens regarding the recovery perspectives appear warranted. The projections by the European Commission provide for a return to annual growth of 0.6 percent this year and a level of GDP of 2.9 percent in 2015. The leading Greek economic think tank, the Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE), is slightly more optimistic for 2014, forecasting that the Greek economy will grow by 0.7 percent.

The gradual but uneven economic recovery and the outlook for 2015 have prompted international credit rating agencies to start upgrading Greece again. In September 2014 Standard & Poor’s upgraded the long-term sovereign credit rating to B from B- with the outlook set at stable in recognition of the “substantial fiscal adjustment” made by the government.

However, this positive assessment is balanced against concerns about the government’s political resolve to continue implementing the agreed structural and institutional reform agenda mandated by the troika. It remains to be seen to what extent better (economic) times are appearing on the horizon.

There are equally good reasons to be cautiously optimistic as well as to retain a healthy dose of scepticism about Greece’s medium-term economic outlook. Two indicators deserve special attention.

One factor that could lead to turbulence concerns the economic effects of the EU’s sanctions regime against Russia and the counter sanctions adopted by Moscow because of the Ukraine crisis.

The Russian sanctions on EU food imports threaten to adversely impact the recovery prospects in Greece, in particular in the agricultural sector and its export capacity. The value of trade between both countries totalled 9.3 billion dollars in 2013, mostly in gas, oil and food products.[2] Tourism arrivals from Russia in the coming year could also be negatively affected if the sanctions regime is maintained or even escalated.

Another concern is continued stagnation in the eurozone, in particular among Greece’s most important trading partners, i.e. Italy, France and Germany. Considering the country’s weak export performance in 2013 and 2014, any further slowdown in demand for Greek products and services from this trio of eurozone members would unfavourably impact on the notion of an export-led recovery in Greece during 2015.

Since the start of 2013 Greece’s export capacity remains a work in progress and is puzzling policymakers as well as analysts. As graph 2 illustrates, the economy’s export performance is on a declining trend with occasional wild swings in opposite directions, for example, in April and June, respectively. For the second year running, Greece will register a decline in exports in 2014.

*Read the original article here

Be the first to comment on "Is there (sustainable) growth in Greece?"