The cure-for-all austerity theory faces its biggest challenge in 2013 in Ireland. After three years of forced hibernation under a bailout, the Irish government must now prove it can tap the markets to finance growth.

The cure-for-all austerity theory faces its biggest challenge in 2013 in Ireland. After three years of forced hibernation under a bailout, the Irish government must now prove it can tap the markets to finance growth.

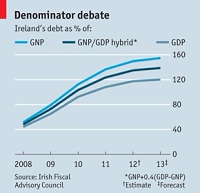

The Economist said it looks like this will be the case, because the cost of the 10-year credit for Ireland has decreased to some 4.5 percent. But, there is a huge ‘but’. In spite of the Draconian austerity–or because of it–Ireland’s public debt per gross domestic product (GDP) ratio has kept rising and it is now 120 percent.

Furthermore, for some analysts it is the gross national product (GNP) the figure that should be used to understand the real volume of debt of the country. In Ireland, the GNP is smaller than the GDP because there is a high level of foreign investment that come in and take their profits away of the Irish economy afterwards. The gap is quite noticeable, indeed, with a GNP almost 33 percent smaller than the GDP.

Comparing against the GNP, Ireland’s public debt is at least 160 percent. In fact, the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council recommends exactly that, to be aware of the GNP-GDP difference, and favours a debt per GDP calculation of 140 percent.

Whatever figure you prefer, the question is that it is a considerable amount of government debt. Worse, the GDP and the GNP are stalled precisely because of the severity of the austerity programme: growth was of less than half a percentage point but the unemployment is now double since 2008. In these circumstances, the debt ration is still expected to go up.

Within the eurozone, Ireland is more embedded into the common currency system than other countries. Its dependence on foreign investment is higher, and it has so far been a receptor state of European funds. A change of economic model seems unassailable right now. Yet, to carry on, Ireland needs to grow. The eurozone must change course or Ireland–and other neighbours, too– will be definitely doomed.

Be the first to comment on "The Irish economy’s riddle"