Things seem to go better from the point of view of actual indicators. Spain’s GDP was positive in the last quarter of 2013; the Labour Force Survey (EPA for its Spanish initials) and the monthly Unemployment Register bring net improvements in January 2014. However, we must say that the main reason behind this positive trend is the continuous drip of people who unregister the public employment service.

Nonetheless, on a five-year perspective, since the crisis began the unemployment rate remains at 26% despite the fall in active workers, and the GDP levels are below those registered in 2009. They are hopeful but weak data, because we cannot see in them a definitive and sound recovery.

The negative thing is that, if we look at this slight recovery within the financial context, things don’t seem so positive after all. Debit balances in financial sectors have barely changed and balance sheets in banking, businesses and families remain highly negative. The Spanish government presents a deficit and financing needs virtually the same as last year.

The so-called renewed confidence in Spain is due (they say) to the foreign sector’s financial contributions. However, most of the stable capital on the long-term (i.e. direct investment) doesn’t provide a sign of increasing strength.

The banking bailout, which was apparently positive according to the European Union, was unable to get the banking credit flowing towards non-financial sectors. Last December, credit to households and businesses kept falling at an annual rate of -4.8%.

Macroeconomic variables don’t encourage optimism, especially because inflation in the euro zone is getting closer and closer to the ECB’s red line of zero. The latest data for the underlying index is 0.8% year-on-year, which affects the nominal income used to pay the accumulated debts. Even though it also involves the risk of falling into a “soft” deflation similar to the Japanese one, the European authorities seem satisfied with the current state of affairs and prevent the ECB from doing something so as to reinforce the nominal growth.

That’s why we are still in the melancholic loop of low growth, with an inflation well below the ECB’s target, which dwindles the process of getting out of the debt. Moreover, it doesn’t encourage investments on the long-term and makes banks lending money at tougher conditions.

We live since 2012 trusting in Draghi’s word and his well-known OMT. However, one can see that, if the OMT were necessary, the Bundesbank would block it! And the worst thing is that many people can already see this scenario in the near future.

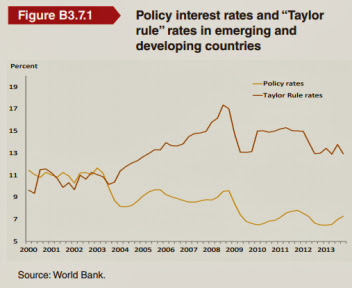

Such crash can be perceived in the sudden braking of the emerging countries, which were living during 5 years thanks to the capitals that ran away from Europe in 2005. The following chart (courtesy of Mr. Ambrose Evans-Prichart) shows the period of economic prosperity in these countries:

We can see that the emerging countries were carried away by the huge amount of capital they received, which permitted excessive growths in demand. Now these countries are called into question because of their excesses, and all those funds they gathered in the last 5 years are running away once more.

That’s why these countries are trying to tighten their monetary policy, but the process is quite difficult and generates volatility in the markets, which involves the quest for safe havens. In the first wave of runaway capitals, which took place last year, the chosen safe haven was the euro (because there was the threat of slowing down the FED’s QE). That’s the reason behind the sharp fall in the German risk premium. However, the appreciation of the euro damaged the exportations of the Eurozone’s countries.

The appreciation of the euro, in a deflationary context as the current one, may be the last push so as to cross the ECB’s red line and reach a Japanese style deflation. That would be alarming, because it is really difficult to fight against a deflationist trend once prices are falling due to the rise in the interest rates.

The more the monetary authority tolerates that the inflation gets closer to zero, the higher the possibilities of a general fall in prices. A very low inflation may work as a deflation, as Paul de Grawe said.

Be the first to comment on "The Threats of Emerging Countries For the Euro"