Two key reasons account for this severe deficit. Firstly, the depositor outflow of the past years has not been reversed to a degree that would improve the liquidity position of Greek banks and hence their lending capacity.

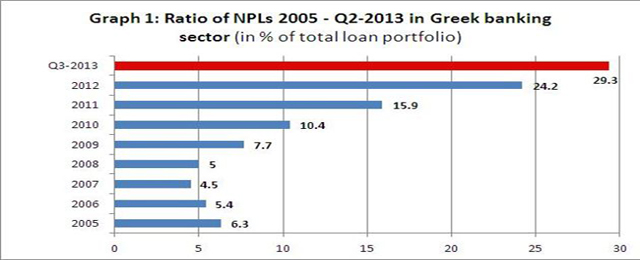

Secondly, the multi-year economic contraction has severely impacted on citizens’ capacity to meet their repayment obligations on mortgages, credit cards and corporate credit. Greek banks are therefore sitting on an ever-rising share of non-performing loans (NPLs), which badly affect their lending capacity.

Both factors contribute to impair balance sheets and are the main reason why a lending recovery has yet to materialize itself in the Greek real economy.

Credit contraction to private households and businesses is happening at an uninterrupted pace for more than two years now. Put otherwise, since the beginning of 2011 Greek banks have not been in a position to adhere to their core function, namely to provide affordable credit to the demand side, in particular those small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that take up over 90 per cent of the Greek corporate landscape.

Significant balance sheet risks because of NPL formation and low liquidity levels continue to challenge the operational capacity of Greek banks after the recapitalisation. In addition, the capital stock of the Greek real economy remains too thin and far too dependent on bank dominated lending capacity. Any attempt of the Greek real economy to regain its footing and identify new growth paths can only have a realistic chance of succeeding if and when Greek banks become part of the endeavour.

Source: Kathimerini, August 29, 2013, economic section, page 3.

This partnership to sustain what some observers have started to call Greekcovery has yet to be operational and yield results that signal a turnaround. We must rather voice concern over the possibility that domestic lenders will first and foremost concentrate their lending activities on established [large] corporate customers and thus favour those businesses which after five uninterrupted years of recession are still in the position to provide sufficient collateral for the credit facilities they require.

In such an admittedly dire outlook the remaining constituency of potential customers will be fighting amongst themselves to gain access to loan tranches that are too little too late and are advanced under conditionality requirements that will prove difficult, if not impossible, to finance.

Credit crunch and disconnecting from financial services

The severity of credit constraints in Greece’s real economy is further illustrated by two structural problems that increasingly reflect the dire conditions under which private households and businesses try to keep their heads above water.

On the one hand the Greek government has been successful through a multi-year austerity course to bring down wages and salaries in the public sector. This process of wage contraction has been supplemented by private sector redundancies and an unprecedented number of new sectoral and firm-level bargaining agreements, which have sought to reduce labor costs in the real economy during the past three years. According to the Central Bank of Greece unit labor costs have declined by more than 27 per cent between 2010 and Q3-2013.[1]

But this apparent success story risks being undermined by a development in the opposite direction that constrains the recovery attempts. The high costs of capital for businesses constitute the most significant obstacle to affordable and timely lending facilities. The central problem of the real economy in Greece is today not anymore the high [unit] labor costs. Rather, the key impediment is the elevated credit costs for capital and thus the lack of liquidity injections transmitted through Greek banks. In particular towards SMEs, the availability of credit and affordable borrowing rates are handled in a very restrictive manner by domestic lenders.

*Continue reading at The Agora.

Be the first to comment on "When Will Greek Banks Operate as Credit Institutions Again?"