Mo Yelin, Richard Mungai, Yang Ge, Xu Heqian via Caixin | (Nairobi, Kenya) — On the surface at least, tile-maker Twyford Ceramics looks like a precisely stamped copy of the thousands of manufacturers that have earned China the nickname of “Workshop to the World.”

Located about an hour’s drive outside the large city of Neiluobi, population 3 million, the company cranks out thousands upon thousands of the low-tech products that China is famous for — in this case, ceramic tiles that will end up decorating floors of homes, offices and other buildings. The massive factory complex sprawls over 60 acres, the size of nearly as many American-football fields, in an undeveloped and remote area well outside the city.

The first of its quarter-mile-long production lines went into service last year, with two more phases planned that will ultimately carry a total price tag of about $75 million. The complex is a joint venture between the Sunda Group and Keda Clean Energy Co., two companies from China’s recently minted crop of commercially oriented, private-style manufacturers and traders.

But the similarities end there.

A zoom out from the complex reveals that Twyford is in an arid area of Africa’s famous Rift Valley, and Neiluobi is just the Mandarin transliteration of Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, a country on the continent’s east coast north of neighboring Tanzania. The area has been isolated for decades, populated by the famous nomad Maasai community and known mostly for wildlife roaming its plains and views of the snow-capped Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest peak.

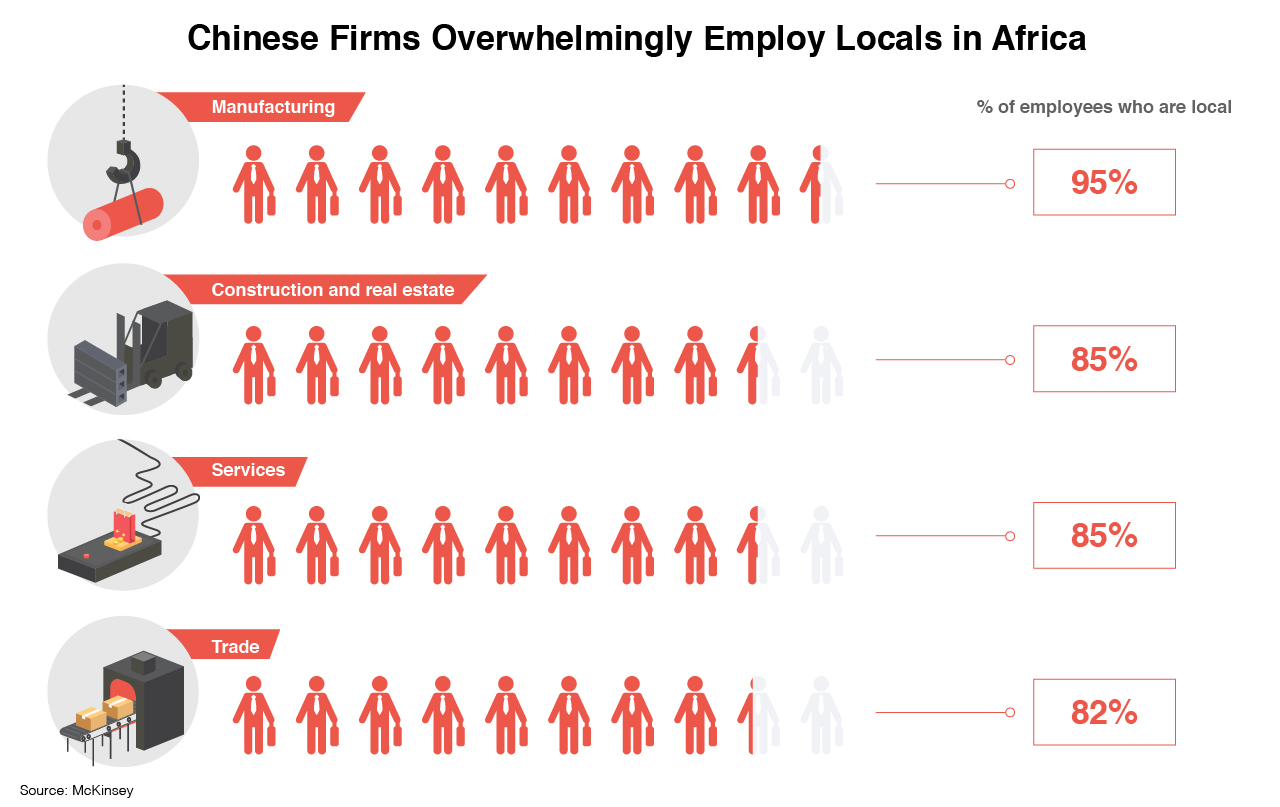

A zoom into the complex reveals an equally un-Chinese landscape, with hundreds of local Kenyans manning humming production lines and tending to other tasks on a recent work day, the scene interrupted only occasionally by a Chinese manager. The company is already about 93% staffed by locals, with plans to raise that figure to between 95% and 97% within five years, said Li Ruiqin, the factory’s managing director.

“We are now in an initial stage of learning, and you can’t compare the current workers with Chinese workers,” said Li, 36, who lives by himself in Kenya apart from his wife and two young children in China. “But Kenyans are learning very fast. We are optimistic, we have a plan, say in three years, that at least the line group managers and supervisors can be replaced by local Kenyan colleagues, which we have already put into the company’s localization policy.”

The native of China’s Shandong province added that Twyford is also moving beyond Kenya, with another plant opening in Ghana earlier this year and a third under construction in Tanzania.

Twyford is one of a new generation of Chinese companies setting up shop in Africa, laying the foundation for what experts believe will become a major economic engine for the continent. Unlike previous generations of Chinese investment in the continent that were at least partly politically motivated, this latest is coming largely from China’s young private sector looking for growth opportunities and to escape rising costs at home. What they are doing is similar in many ways to what Westerners did in China back in the 1980s and 1990s, when many came to the country to make basic products that could take advantage of the low Chinese labor costs.

Like that group of Western pioneers, the new group of Africa-based Chinese manufacturers also face certain challenges. Those include cultural barriers, as well as biases against outsiders whose past investment patterns have given them a less-than-stellar reputation as exploiters of Africa’s national resources. McKinsey report: Dance of the lions and dragons: How are Africa and China engaging, and how will the partnership evolve?

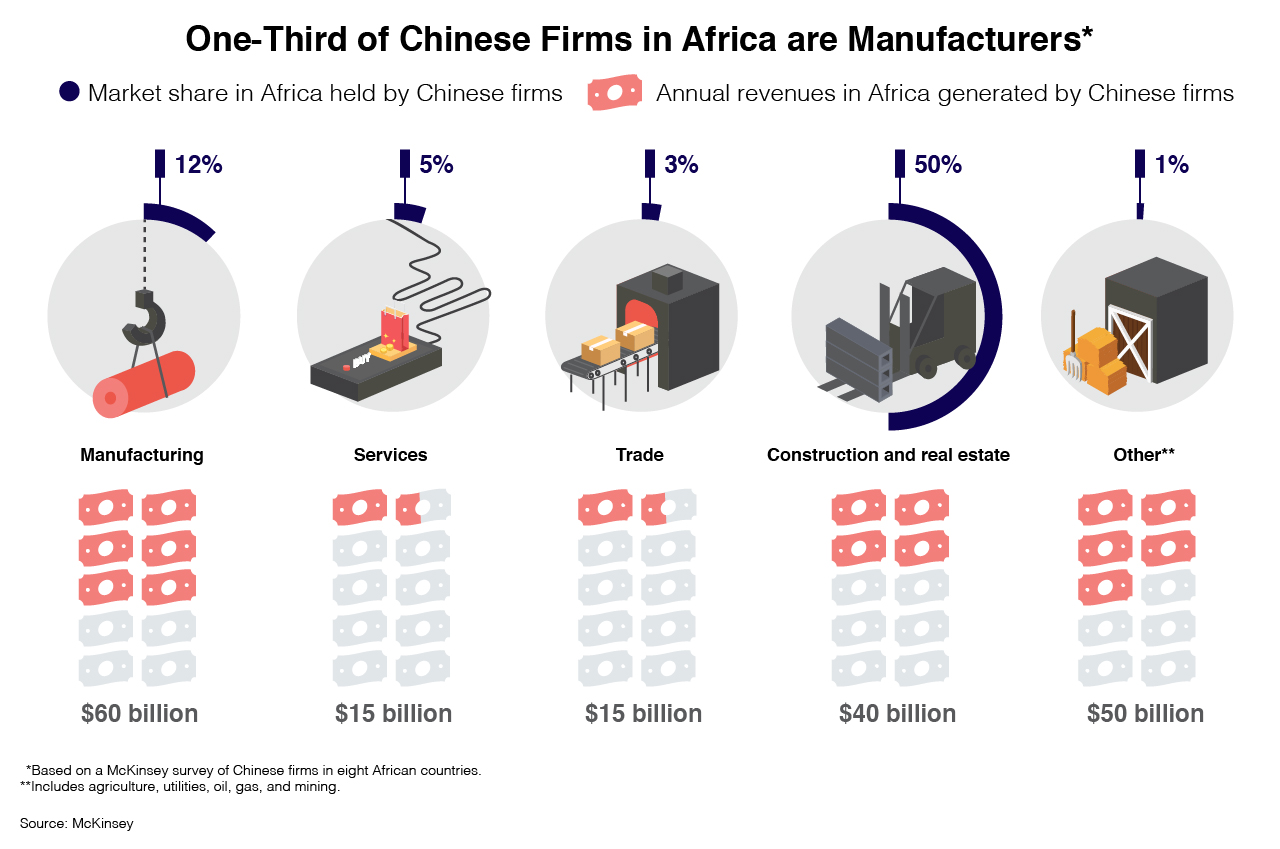

But the growing contribution by Chinese manufacturers to Africa’s economy is hard to ignore despite its low profile. Chinese firms are now responsible for about 12% of Africa’s $500 billion worth of industrial production each year, according to a report published this year by McKinsey & Co. “Africa looks like what China was 20 years ago.” Irene Sun, McKinsey consultant

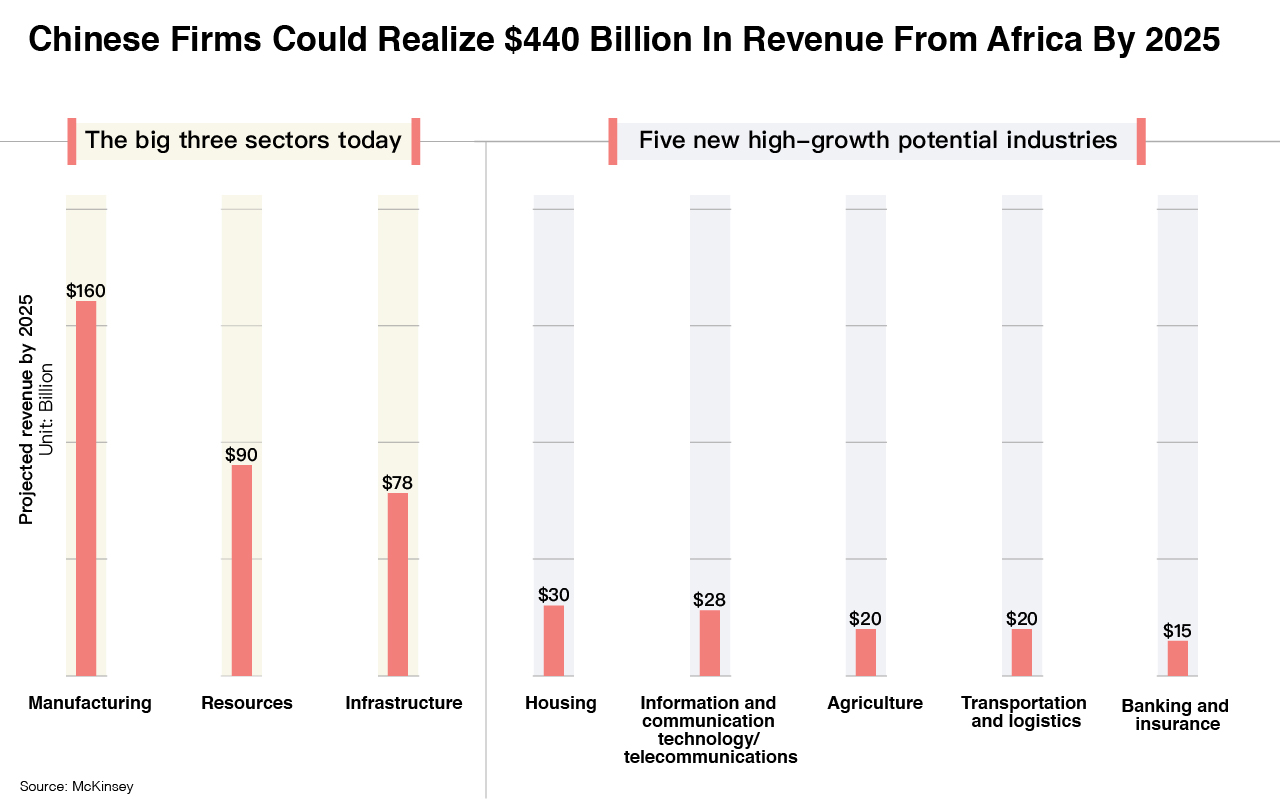

That same report found that nearly a third of Chinese companies in Africa are now engaged in manufacturing, possibly numbering more than 3,000 in total, making them the single largest group of investors from China. In an accelerating growth scenario extrapolated from current trends, Chinese manufacturing in Africa could be worth as much as $160 billion in annual production by 2025, more than the entire amount of all bilateral trade between the pair last year.

“Africa looks like what China was 20 years ago. In 1990, China accounted for 2% of globally manufactured output with a population of 1 billion people. Africa right now has 1 billion people and on the order of 1% to 3% of global output,” said Irene Sun, a consultant at McKinsey.

“The common denominator is profitability. You see all kinds of products (being produced by Chinese in Africa). Just to give a smattering, you have steel mills, heavy industry, all the way to things like hair extensions for local African use.”

Commercially driven

The quiet manufacturing surge follows more high-profile waves of China investment from its earlier days of opening to the outside world starting in the 1980s. The earliest of those came in resource investment, as China eyed the continent’s untapped supplies of crude oil, minerals and other raw materials to feed its own hungry economy. Those early days in some ways hurt China’s reputation with local Africans, as many came to see the Asian nation as an exploiter of their resources without much regard for their own economic development.

More recently, China has also begun exporting its infrastructure-building prowess, partly in a bid to improve its image and also to facilitate its trade with the region. The small East African nation of Djibouti exemplifies that trend, receiving more than $10 billion in Chinese investment over the last few years to help develop its ports, railroads, pipelines and other infrastructure connecting it with energy-rich neighbor Ethiopia.

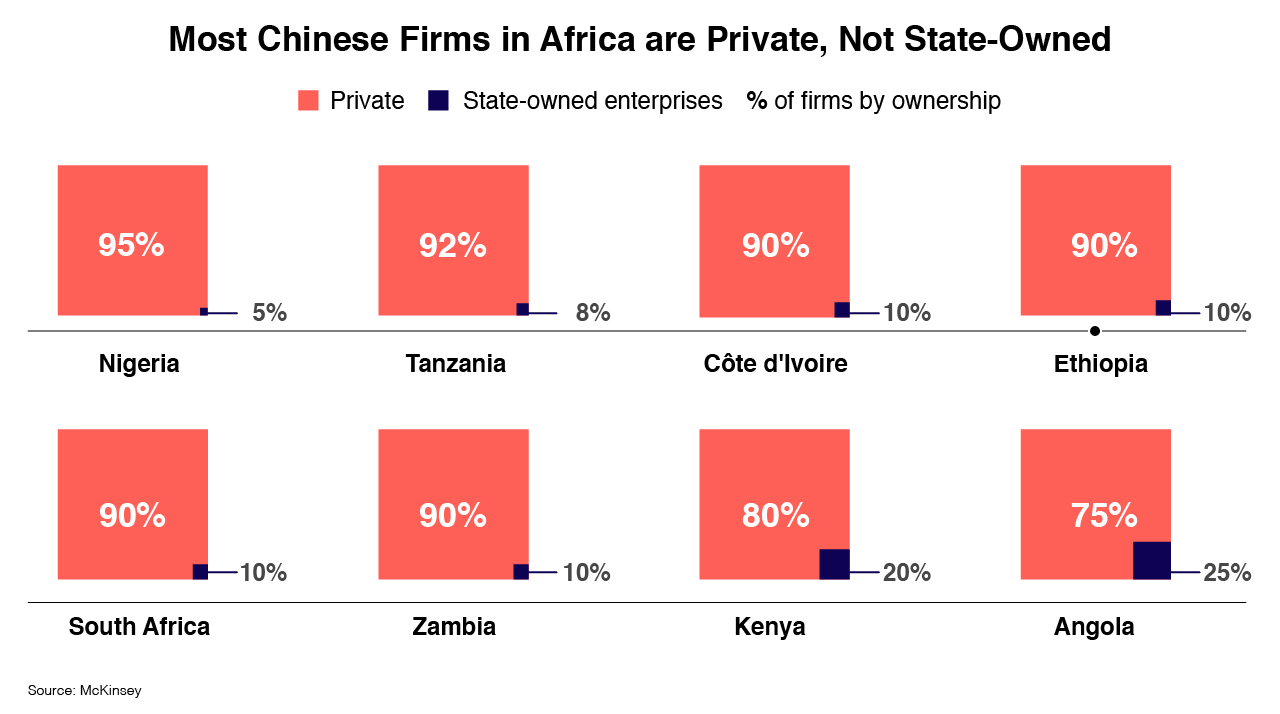

But the latest wave differs sharply from those earlier two in several ways. Most importantly, the manufacturing wave is being driven mostly by commercial factors, which means the big majority of investment is coming from private companies using their own financing.

Unlike earlier investors that were mostly state-owned giants backed by Beijing money and political agendas, most of the latest investors are simply moving production offshore to escape rising costs at home and avoid Africa’s high import tariffs. Twyford exemplifies the group, estimating its products are 30% cheaper when produced locally than comparable ones shipped from China.

“Faced with increasing labor costs, Chinese manufacturing firms have begun relocating to countries with lower wage rates, including several in Africa,” said Jeremy Stevens, a China-based economist at South Africa’s Standard Bank, one of the continent’s largest lenders.

“In the past, the key motivating factors for manufacturing firms to invest in Africa were to circumvent U.S. and EU trade restrictions on Chinese products. Today this is no longer the case: The top reasons for investing in Africa were to gain access to largely untapped local consumer markets and avoid competition in an increasingly saturated Chinese market.”

Trading roots

Many companies setting up Africa shops began life as importers of Chinese goods to the continent. But as the cost of those goods rose, combined with the impact of shipping costs and import duties, many realized it might be cheaper to produce locally. Accordingly, the current range of products is currently dominated by lower-end goods, especially heavy and bulky items that are expensive to ship and relatively easy to produce locally. “We should fully be localized and integrated into Kenyan society” Yocean CEO Dylan Yu

Those include many of the usual suspects, such as building materials and textiles. But the list is also expanding rapidly to include higher value-added products like cellphones, home appliances and even cars. Big-name examples of that moving up the value chain include appliance giant Hisense Co. Ltd., which makes flat-screen TVs and refrigerators in South Africa, and auto giant FAW Group Corp., which makes cars in Nigeria.

While some of China’s top manufacturers are starting to look at Africa, the vast majority moving to the continent so far are no-name companies that mostly keep to themselves and maintain a low profile. With a few notable exceptions, most produce exclusively for local consumption, both for the country where they are based and also surrounding markets.

One company making the move up the value chain is Yocean Group, which, like Twyford, is in Kenya, an attractive location for Chinese manufacturers due to its relative political stability and proximity to a number of major markets. Other countries that appeal for similar reasons include South Africa in the continent’s south, Ethiopia in the east, and Nigeria in the west, observers say.

Like Twyford, Yocean also follows a common pattern by tracing its roots to the region as a trader of Chinese-manufactured goods. When it first registered in Kenya in 2011, it traded in electrical materials such as supply cables and conductors. But the company saw its chance for better things when the government adopted policies to boost manufacturing in 2014, CEO Dylan Yu said.

It quickly identified transformers as a product it could produce profitably, catering to local needs as the country built out its power infrastructure. Yu pointed out that Kenya was reliant on imports for its transformers for years, mostly from India. His company began production last year, and his efforts at localized manufacturing have won him the trust of both the government and clients, especially the biggest state-owned utility, Kenya Power.

“As a local manufacturer, we should fully be localized and integrated into the Kenyan society,” Yu said in a recent interview at his factory, which employs about 100, more than 80% of them local Kenyans, in an industrial park about a 15-minute drive outside Nairobi.

“We never just wanted to be a trading company. Rather, we have a goal to move higher and become deeply integrated into the country’s electricity system.”

Unlike Chinese companies of the past that may have tended to avoid too much involvement in the local community, many manufacturers from the new generation like Yocean say they are trying to become more involved and integrated with the local community. Such involvement minimizes risk of misunderstanding and resentment. And Yu pointed out that as a member of the Kenya Association of Manufacturers, the country’s biggest business association, Yocean has a chance to influence government policy.

Hiccups and other risks

While profits are the main driver behind the Chinese manufacturing boat to Africa, people from both continents admit that hiccups and other risks exist in what could become one of the world’s largest global economic migrations in the first half of the 21st century.

Political instability is always a major risk, which explains the popularity for the relatively stable markets like Kenya, Nigeria, Ethiopia and South Africa. Another big risk could be increased government scrutiny as Chinese companies’ influence grows, since they are sometimes more lax than Western counterparts about following local labor and environmental laws, according to the McKinsey report.

Smaller risks also exist in terms of local perceptions. Chinese manufacturers got an abrupt reminder of such sensitivities closer to home in 2014, when thousands of angry local protesters in Vietnam burned and looted factories that they believed were Chinese following a flare-up in a territorial dispute between Hanoi and Beijing. No such major flare-ups have occurred in Africa yet, though managers and employees acknowledge that sometimes misunderstandings occur.

One such case happened in the early days at Twyford when locals near the factory mistook dust created in the tile-making process for smoke, leading to rumors about potentially dangerous pollution being created. Lemayan Ole Kunga, a resident who lives near the factory, said that some people also believed that pasture was drying out faster than before in the areas surrounding the factory. But considering its economic benefits, issues like that and pollution have become less important among locals more recently, he was quick to add.

“Just a few years ago, this area was very insecure due to local young men who had turned to crime due to lack of jobs,” he said. “But this has changed since Twyford came. Most of those people are now employed by the Chinese.”