Keith Wade (Schroders) | The recent G20 and IMF meetings saw the international community endorse the all-in approach of policymakers in response to the Covid pandemic.

Budget deficits have soared and central banks have stepped up their support through asset purchases and cutting interest rates.

Those trends are now being reinforced across Europe and the US as another wave of Covid-19 hits. Further restrictions and lockdowns mean governments are extending support and central banks are easing further.

News of a breakthrough on the vaccine front means that help is on its way, but there can be little doubt that for now this is the right policy path to follow and will continue to be so as the world economy slowly normalises.

Covid is both a cyclical and structural shock as alongside the immediate collapse in demand it has accelerated secular trends which have been developing for some time. Those trends will force a reallocation of resources and bring dislocation and displacement to economies and workers.

Policy support will be needed beyond the immediate response to smooth the adjustment to the post-pandemic economy as old jobs are lost and new ones created.

Investors have embraced the official approach with equity and credit markets recovering strongly since the slump in March. It is too early to worry about the level of government debt, which the IMF estimate will reach levels last seen after World War 2 for the G20 economies. Nonetheless, we should recognise that this policy response has brought an unprecedented level of financial repression and official involvement in the economy.

As the demands on central banks increase, investors will find that something will have to give. The investment landscape is changing in ways which, in our view, will prove hard to reverse.

The evolving role of central banks

Central banks have traditionally been the independent guardians of stability in the economy and markets. They have now found themselves playing a key role in supporting fiscal policy. By driving interest rates down along the yield curve, they are clearing the path for governments to issue significantly higher levels of debt.

Monetary policy – for so long focussed on inflation and financial stability – is becoming increasingly subservient to fiscal policy.

The clearest evidence of this was seen in the initial phase of the Covid crisis, between February and September, when central banks stepped up asset purchases to absorb the surge in government borrowing.

Figures from the IMF show that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) bought nearly 60% of US central government debt during that period. It was closely followed by the Bank of England (BoE), which bought 50%. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and European Central Bank (ECB) each bought more than 70% of their government’s issuance.

The BoE has just committed to buying another £150bn, while the Fed, ECB and BoJ continue with their substantial asset purchase or QE programmes. At the same time, interest rates in all these economies are either close to, or below zero.

Although this can be seen as an appropriate emergency response, looking further out it is hard not to conclude that central banks will play a significant role in bond markets for a considerable period.

We do not expect the US to experience the same economic malaise as Japan, but the unprecedented level of official involvement means the US Treasury market could be going the same way as the Japanese government bond (JGB) market.

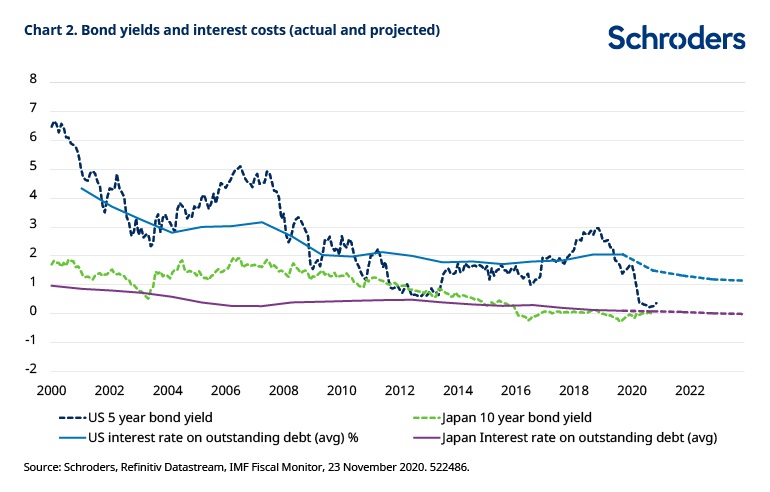

The BoJ now determines pricing in the JGB market. It effectively sets yields along the curve through asset purchases and direct action to target ten year yields at around zero through its policy of yield curve control (YCC)

The risk of “Japanification” for the Treasury market

The need to sustain a high government debt level clearly dominates monetary policy in Japan where the BoJ now owns just under 45% of the JGB market.

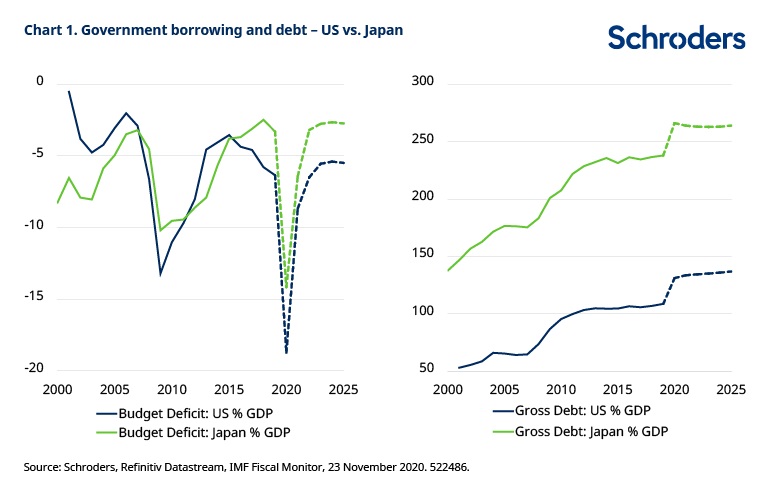

Ten-year bond yields have been held at zero for the past four years, in line with the BoJ targeting in its YCC policy. This is against a backdrop where government debt as a share of GDP in Japan is expected to reach 266% this year and the budget deficit 14% of GDP. The government has urged investors in Japan to seek alternatives to JGBs. This is implicit recognition that there will be no rapid return to normal market funding of the budget deficit.

Could we see a similar “Japanification” of the US Treasury market? The latest figures show the US budget deficit at $3.6 trillion in the fiscal year just ended September 30, just under 19% of GDP.

Looking at the current trajectory, on IMF projections the deficit is expected to fall sharply next year to 8.7% GDP as economic activity recovers.

However, despite further economic growth, borrowing only slows marginally in subsequent years, falling to 5.5% GDP by 2025, according to the projections. Consequently, government debt continues to rise as a share of the economy to 137% GDP.

Japanese government borrowing is also at record levels this year and like the US is expected to fall sharply next year. But, unlike the US, borrowing slows to just under 3% GDP by 2025 and the gross debt to GDP ratio stabilises at 264% GDP.

Clearly, Japan’s debt is significantly higher than the US’. However, it is stable rather than rising. This reflects the poor position of US government finances before Covid-19, where the budget deficit was running at 6.3% of GDP at a time when the economy was doing well with unemployment at less than 4%, a 50-year low. (In net terms the comparison is less stark with Japan at 180% GDP versus 114% in the US).

Arguably, the US deficit should have been close to balance or even in surplus at this point in the cycle. Estimates suggest that the structural or cyclically-adjusted budget deficit in the US, is expected to remain at close to 5.5% over the next five years. By comparison, the Japanese equivalent is just above 2.5% GDP.

These figures are based on a central case where the US recovers and does not incur significant debts as a result of its contingent liability programmes. This is where the government has extended or underwritten credit to the private sector.

It is possible that the public finances will turn out better. But should the economy take longer to recover, or the government incurs significant debts as a result of its official support programmes, the picture would be worse.

Tighter fiscal policy?

Essentially, the US government faces the prospect of having to tighten fiscal policy to bring the deficit onto a more sustainable path (where debt to GDP is either stable or falling).

Spending pressures are intense, with healthcare demands rising significantly in the wake of the pandemic, adding to already adverse demographic trends for health and pensions. President elect Joe Biden has said he will raise taxes, but a divided Congress will almost certainly prevent him from doing so.

Austerity would seem to be out of the question for the Democrats and indeed many Republicans, especially given the close standing between the two parties where unpopular policies will be politically expensive.

Or, financial repression?

So, in the absence of fiscal tightening, the Fed will have to continue to keep downward pressure on interest rates to prevent borrowing costs from rising significantly and risk de-stabilising the US Treasury finances.

We have backed out the borrowing costs from the IMF projections which show that the implied interest rate on US government debt is projected to fall from 1.5% in 2020 to 1.2% GDP in 2025 (chart 2).

This can only be achieved by refinancing existing debt at lower interest rates, meaning that monetary policy must be supportive in keeping rates low along the yield curve, not just at the short end.

As the BoJ has demonstrated in driving down funding costs, this means using all policy tools: interest rates, forward guidance and asset purchases.

At present, the Fed holds just over one-fifth of the Treasury market on its balance sheet. It is possible though that, like the BoJ, the Fed finds that as asset purchases mount up it has to turn to more drastic measures. Even these low interest rates are not sufficient to prevent US debt from continuing to rise. Yield curve control could come onto the Fed’s agenda.

Pleasing all of the people all of the time

At this stage there is little conflict for the Fed, or other central banks, as ultra low interest rates and increased QE can meet all the aims of monetary policy. Governments can finance their deficits with ease, there is little threat of inflation and although risk assets have rallied strongly, we are not in bubble territory in our view.

However, going forward as the economy recovers excess savings and excess capacity will diminish. And as private sector demand for capital begins to rise, there will be pressure to tighten monetary policy. Unless central banks act, inflationary pressure will begin to build and/or financial instability may increase as stronger activity sends investors out of cash into riskier assets. Ideally, governments would choose this as the moment to raise taxes or cut spending, but fiscal policy is not a flexible tool being dependant on the timing of budgets and the political cycle.

As a result, the need to support the government’s funding programme may well limit the Fed’s ability to respond to rising inflation, or increased market instability in the future. Tighter monetary policy and higher interest rates would risk political ire and the likely loss of any vestige of independence.

Japan has been unable to generate higher inflation, but the BoJ has taken increasing control of its government bond markets and forced investors into other assets. The US economy is better-placed in our view to generate growth, but in starting from a weak fiscal position the surge in debt will create policy dilemmas for the US central bank.

Ultimately, the Fed will not be able to please everyone. Greater official intervention in the Treasury market and financial repression will continue as fiscal needs dominate: the Treasury market will become less responsive to economic conditions and in this respect turn increasingly Japanese. Two or three years down the road though the cost could well be more inflation and greater volatility in financial markets.