Last week, People’s Bank of China (PBoC) Governor Zhou reaffirmed his concerns about the stability of the financial system in an article. Susan Joho, economist at Julius Baer points that he surprisingly spoke boldly of the risks of a Chinese Minsky moment in the following up on his speech during the Chinese party congress.In fact, Zhou called for the need for broadened equity funding and direct finance to reduce the risks of a future financial crisis.

The 69-year old, longest-serving and well respected PBoC Governor, who is expected to retire soon – maybe as early as next March – could have used the occasion at the end of his career as a rare moment to say what he really thinks. His pessimism also stood out in stark contrast to President Xi’s grand talk of a “new era”.

However, when looking more deeply, their views can be seen as two sides of the same medal.

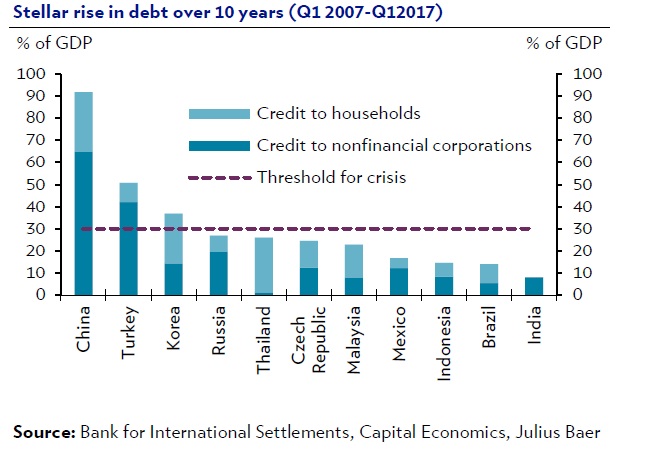

China not only wants to evolve by moving up the much-cited value chain (Xi), but it has to (Zhou). Risks arising from a huge pile of debt are looming in the background, making quick action to find new growth drivers and contain risks from debt necessary at the same time. China’s debt has risen at a stellar pace over the past decade and warning signs are flashing.

Empirical research has shown that economies with debt rises of more than 30% of gross domestic product (GDP) over ten years have usually ended up experiencing a banking crisis. According to Susan Joho, China’s rise at 90% is way above this threshold and “the leaders know it well.”

Zhou’s comments for “both preemptive measures and reactive solutions” are to be seen in that light. It is a balancing act for the government to let growth cool down, but not too much, to avoid triggering a crisis.

Going forward, we expect the government to protect its economy should conditions deteriorate too rapidly. The central bank, however, may increasingly play the role of the bad cop to keep absolutely needed reforms to stabilise the debt alive.