Alicia García herrero (Natixis) | During the past fifteen months after the outbreak of the Ukraine war, China and Russia’s trade value increased by 36.5% compared to pre-war levels, showing their much-enhanced ties in merchandise trade. Meanwhile, in addition to the upswing of the headline amount, some new patterns in their trade structure are also worth watching. For example, Russia has moved up rapidly in the rank of China’s external energy suppliers with a share of 17.2% trailing 12 months by April 2023 while the reading was just 13.3% in 2021. China has also stepped up its export of several major manufactured goods to Russia which interestingly concentrated on transportation and construction, while the once largest export of office apparatus has declined. In this note, we will focus on the latest development in the two countries’ bilateral trade.

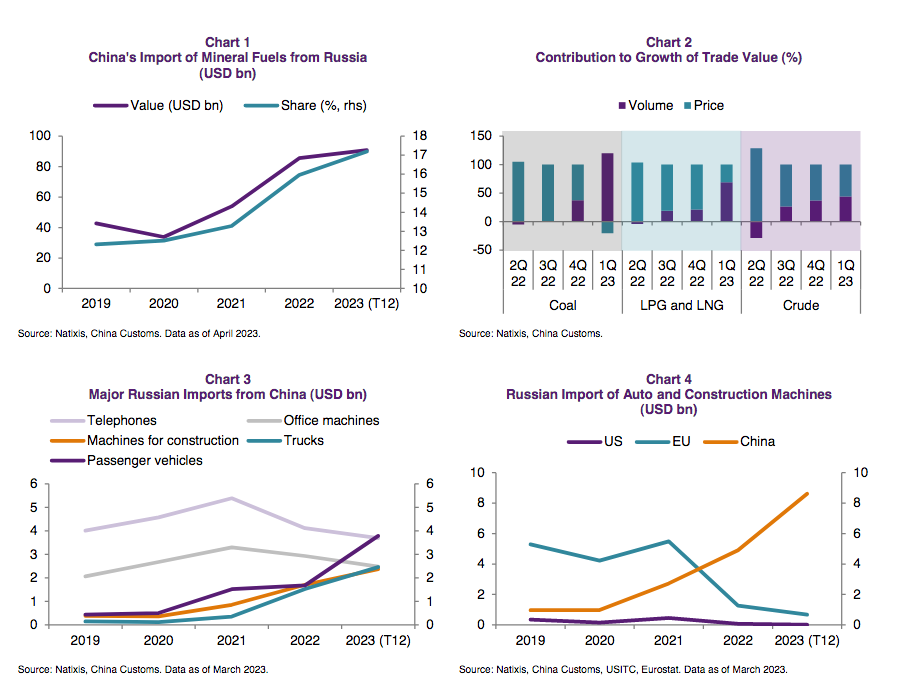

From China’s perspective, mineral fuels have long been the largest import item from Russia, which recorded $54 billion (or 13.3% of China’s total fuel import) in 2021. But the number has further risen to $91 billion (or 17.2% of China’s total fuel imports) trailing 12 months by April 2023 (Chart 1). In our previous analysis, the increase shortly after the war started was mainly driven by price effect without a clear rise in quantity. However, it is now a surge in the volume of fossil fuel imports that is behind the sharp increase in the first a few months of 2023. As in Chart 2, we can see that quantity’s contribution to growth has more than doubled for coal and liquified gases compared to 2022.

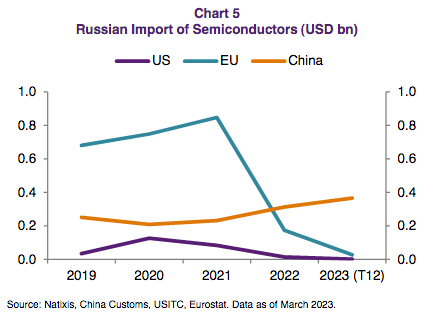

On the other hand, Russia is also expanding its import of certain manufactured goods from China, such as automobiles (both passenger vehicles and trucks) and construction machines such as bulldozers and road rollers, which interestingly reflects the impact of warring on Russia as the once largest import of office equipment dropped significantly. The increment of import of these items from China has offset the decline of import from other major suppliers, namely the EU and the US, as Russia has been becoming alienated from them since the start of the war. Meanwhile, Russia now is also forced to search for alternatives to US and EU chips as a result of the Western sanctions over this strategic sector. However, the increase of chip import from China has not yet been enough to cater Russia’s full needs, at least when looking at the amounts imported from Europe in the past (Chart 5).

All in all, China and Russia are enhancing their trade relations in strategic commodities and manufactures as a response to Western sanctions and as a means to go around them. That said, Russia may not be capable of providing China with as much as what China provides for Russia, and it may be far from enough. Thus, China should benefit less than Russia from this since the Chinese economy outsizes Russia’s by 10 times. On the other hand, China may also face a higher risk of new sanctions or further alienating moves by the West if it gets too close with the internationally denounced warring state.