Alicia García Herrero (Natixis) | Uncertainty about China’s growth prospects next year is unprecedently high. Most importantly such uncertainty hinges more than ever on a single issue: the speed – and smoothness – of China’s opening-up from zero-Covid policies after three years of intermittent lockdowns.

The speed of opening-up is key because mobility is closely correlated with China’s consumption and economic activity, more generally. In fact, we have estimated that, in the course of 2022, the reduction of mobility due to Covid restrictions should have shaved off as much as 2.5 percentage points of GDP growth.

Since November 10, China has been taking steps toward opening-up and turning away from zero-Covid, following the announcement of 20 measures for Covid prevention and control protocols and, only yesterday, 10 more measures to accelerate the process even further and make it a national endeavour. These measures include the fast increase in the vaccination rate of the elderly, especially those above 80 since the vaccination rate remains stubbornly low. In this note, we estimate how long it may take for China to reach vaccination-based herd immunity for this target group of 80 years and above. It goes without saying that protecting a larger share of the population will take longer so this is the bare minimum to consider a still risky – but more feasible – opening away from zero-Covid policies. We are also assuming in this note that China will continue to use its own vaccines to protect its citizens. Any shift to mRNA vaccines would obviously also delay the opening-up even further.

We use the booster vaccination rate for age group above 80 as the indicator of full vaccination. According to the latest data released on November 28, only 40.4% of elderly aged above 80 in Mainland China have received at least one vaccine booster, which falls short by far of other neighbouring economies when they open up, such as Taiwan (63% for 75+ years old) and Singapore (90% for 80+). When calculating the time needed for China to catch up, one important constraint is that boosters need to be administered at least 3 months after the second dose and the second dose should come at least 3 weeks after the first one. Thus, we utilize a rolling simulation of the vaccination progress of all three jabs, namely restricting the subsequent vaccination only to the qualified people with enough time gap.

The result shows that the time gap needed between the second dose and the booster is a critical factor to determine the date of reopening. Since 66% of the elderly aged above 80 (about 23.6 million) have received the second dose, it will only take 3 days for them to get the protection of booster jab if the government can offer 4.8 million dosages every day, which was the pace during the first quarter of 2022. However, if the government aims at a vaccination rate above 66%, it will need to take into consideration of the time gap between the second and the third dose. For example, even if the government wants to vaccinate only 70% of the elderly, it will have to wait for 3 more months, postponing the completion date to early March 2023. On a positive note, reaching 90% only takes 3 weeks more than reaching 70%, which brings us to the end of March in case China manages to keep the fast speed of vaccination reached in the first quarter of 2022. If the speed of vaccination is not increased and kept similar to the third quarter of this year, we would go further to April 6.

What seems clear by now, especially after yesterday’s additional 10 measures, is that China’s reopening will be fast. The low vaccination, together with the rather limited healthcare facilities when compared to other similar cases (such as Hong Kong, Singapore or Taiwan), opens the floor to potential reversals, which have indeed happen in those three economies to different extents.

All in all, the Chinese government’s vaccination target for the most vulnerable population will remain a very important indicator to follow to assess the risk of reversal of China’s currently fast opening-up.

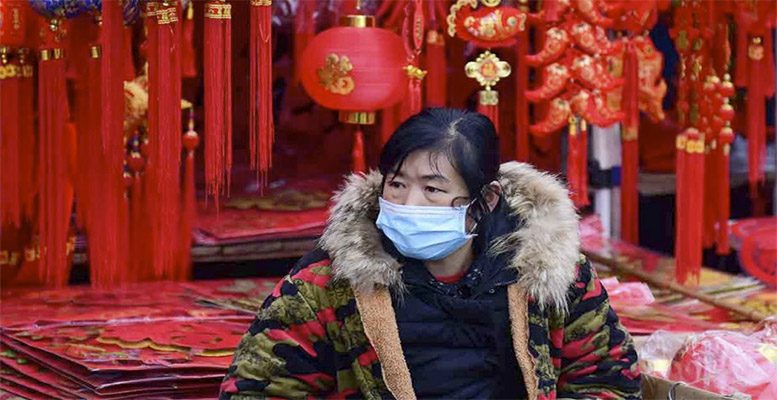

China to open faster than expected but with risk of reversal given low vaccination rate