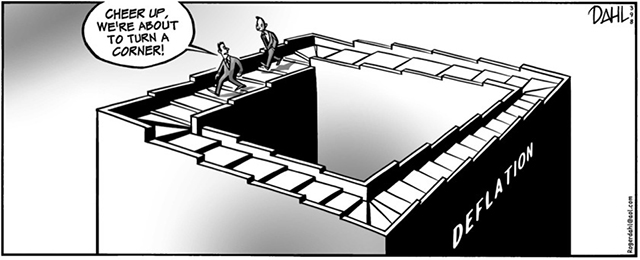

David Andolfatto has a recent post where he questions the “evils of deflation”:

Everyone knows that deflation is bad. Bad, bad, bad. Why is it bad? Well, we learned it in school. We learned it from the pundits on the news. The Great Depression. Japan. What, are you crazy? It’s bad. Here, let Ed Castranova explain it to you (Wildcat Currency, pp.160-61):

Deflation means that all prices are falling and the currency is gaining in value. Why is this a disaster? … If you hold paper money and see that it is actually gaining in value, it may occur to you that you can increase your purchasing power–make a profit–by not spending it…But if many people hold on to their money, this can dramatically reduce real economic activity and growth…

In this post, I want to report some data that may lead people to question this common narrative. Note, I am not saying that there is no element of truth in the interpretation (maybe there is, maybe there isn’t). And I do not want to question the likely bad effects that come about owing to a large unexpected deflation (or inflation). What I want to question is whether a period of prolonged moderate (and presumably expected) deflation is necessarily associated with periods of depressed economic activity. Most people certainly seem to think so. But why?

The first example I want to show you is for the antebellum United States (and shows a version of this chart):

![Deflation can be “good” or “bad”, it depends deflation-evil_1[1]](http://www.thecorner.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/deflation-evil_11.png)

Following the end of the U.S. civil war, the price-level (GDP deflator) fell steadily for 35 years. In 1900, it was close to 50% of its 1865 value. In the meantime, real per capita GDP grew by 85%. That’s an average annual growth rate of about 1.8% in real per capita income. The average annual rate of deflation was about 2%. I wonder how many people are aware of this “disaster?”

People should know that there are “good” and “bad” deflations. In the picture above we see that the real output-price outcome was the result of a shifting AS curve (positive productivity shock).

The next picture gives an example of “bad” deflation, the result of a contraction in AD. In 1933 the opposite occurs when FDR delinked from gold and monetary policy was expansionary, allowing real output to grow strongly with minor impact on prices (given all the “slack” generated by the GD).

![Deflation can be “good” or “bad”, it depends deflation-evil_2[2]](http://www.thecorner.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/deflation-evil_22.png)

The Great Inflation is the prototype example of inflation “running wild” due to excessively expansionary monetary policy.

![Deflation can be “good” or “bad”, it depends deflation-evil_3[1]](http://www.thecorner.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/deflation-evil_31.png)

So, in some cases deflation is really a “disaster”.

And in this day and age of inflation targeting, allowing inflation to fall below target (and letting the price level remain permanently below the “inflation target associated price level”) is tantamount to monetary tightening. More expansionary monetary policy would result in the “counterfactual per capita income”. In this case we don´t have deflation but “inadequate inflation” (in reality, inadequate nominal spending), which can also be (very) bad.

![Deflation can be “good” or “bad”, it depends deflation-evil_4[1]](http://www.thecorner.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/deflation-evil_41.png)

Mankiw in his pdf on aggregate-demand says price-deflation is more expansionary…