Fischer is widely—perhaps deservedly so—loathed in some quarters for his role as the IMF’s “number two” during the Asian crisis of 1997-1998, and the subsequent Russian and Argentine defaults. He imposed what we could call today the “German prescription” for countries in crisis: no devaluation at any cost, fiscal austerity, and liberalization. The results were: forced devaluation, soaring fiscal deficits, banking systems collapses, depressions, and, finally, debt defaults (and, in the case of Indonesia, a revolution).

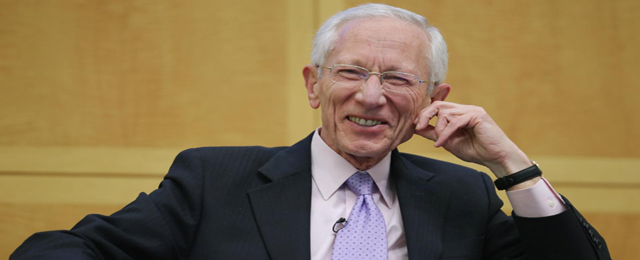

Tired of being yelled at by his new boss, German Horst Koehler, Fischer left the IMF in 2001 and, after a three-year stint at Citigroup, ended up as president of the Bank of Israel. And his policy changed. Radically.

In the Bank of Israel, Fischer conducted an extremely heterodox—and successful—monetary policy based on targeting nominal GDP. That strategy has allowed Israel’s monetary authority to play with inflation and real growth, allowing higher increases in prices when the GDP is low, and vice-versa. In October, Israel had 1.8 percent of year-on-year inflation, so the system has apparently worked.

Under Fischer, the Bank of Israel never had an official nominal GDP target. But it did “de facto”. This is a consequence of Fischer’s belief that central banks’ forward guidance should not exist because they “don’t know” what will happen in the future. No doubt that, in his new capacity, he will have to swallow his own opinions and let the increasingly open Fed speak its mind.

Be the first to comment on "Fischer’s nomination will guarantee a more dovish Fed"