Keith Wade (Schroders) | The rapid growth in US money supply and rising commodity prices are stirring up fears about a return of inflation. The oil price has risen to $50 from a low of $30 in May while money growth in the US has just hit 25% for 2020, its fastest rate on record. These concerns are reflected in inflation-linked securities, with the 10-year breakeven inflation rate in the US having risen from 0.5% in March to just under 2% today.

But how worried should investors be? Is there something unique about the Covid-19 shock which makes inflation more likely?

There are three potential ways that inflation could return.

- Inflation could already be higher, it is just not being measured properly.

- The build up of liquidity could represent latent demand. This could translate into inflation once it is released later in 2021.

- Covid-19 could have an adverse structural effect, such that policy makers will overestimate the supply side of the economy and over stimulate through loose monetary and fiscal policy.

Contrasting fortunes

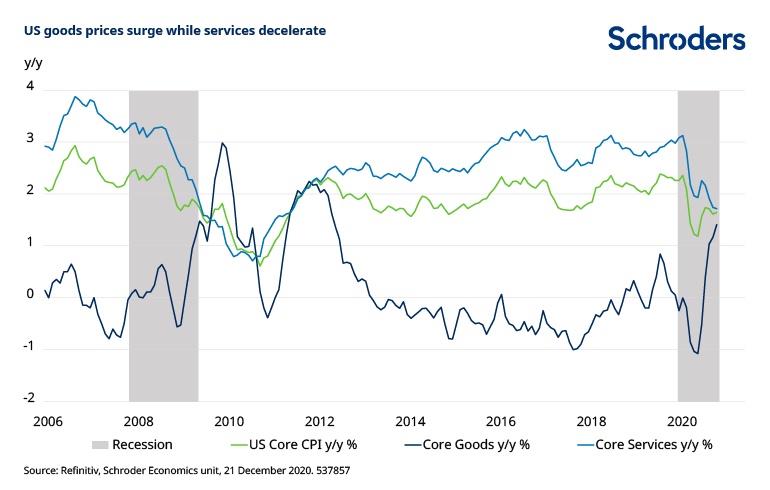

It is true though that there are pockets of inflation. There is a significant divergence between the fortunes of the goods and service sectors at present, with the former enjoying a robust bounce in activity reflecting pent-up demand and the shift to online shopping. Global trade growth in goods has risen sharply with sales of electronics and tech-related products rising rapidly and bottlenecks have begun to emerge. Meanwhile, much of the service sector remains mired in recession, held back by lockdowns and restrictions on mobility.

These divergent fortunes are reflected in the inflation data. Service sector prices are still rising more rapidly than those in the goods sector on a year-on-year basis. However, the latest figures from the US show the gap is closing as the former decelerate while the latter are picking up rapidly, as the chart below shows.

It is likely that service prices continues to slow in coming months before stabilising as the sector returns to normal once vaccines are distributed. The gain in core goods prices should also ebb as much of the recent rise has been concentrated in sales of used cars during the summer as people chose to avoid the risk of contact on public transport and drive themselves. This Covid-related boost is now fading and may well prove to be a one-off as the population gains immunity.

From this perspective, the overall message for inflation is still one of weakness, particularly as services carry more weight in the CPI basket than goods (59% versus 20%).

Nonetheless, worries persist and we can see three areas of concern that could be routes to higher inflation.

Route #1 – Inflation is understated

The first is technical: inflation is not being measured properly and is understated by the usual indices.

Admittedly there are problems with measuring service prices during the pandemic. The closure of many establishments has meant that it has not been possible to collect data in the normal way. Instead some prices have been estimated or simply recorded as unavailable.

The greater source of mismeasurement, however, stems from the change in spending patterns during the pandemic. Covid-19 has forced a shift in spending.

Consumers have cut back on travel, stays away from home and meals out and have increased spending on food and drink at home, for example.

Consequently, the weights used in CPI indices – which are based on normal spending patterns – do not pick up the change in the more restricted Covid-19 economy. Since food prices accelerated and transport prices fell across almost all regions during the pandemic this biases inflation down. Estimates from the IMF and our calculations suggest this is worth about 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points in the US.

Clearly there is a problem here which is unique to the pandemic; however, it should fade as spending patterns return to normal in 2021. The distortion created by the coronavirus leads to a modest one-off understatement of inflation, but should not persist.

Route #2 – Households go on a spending binge

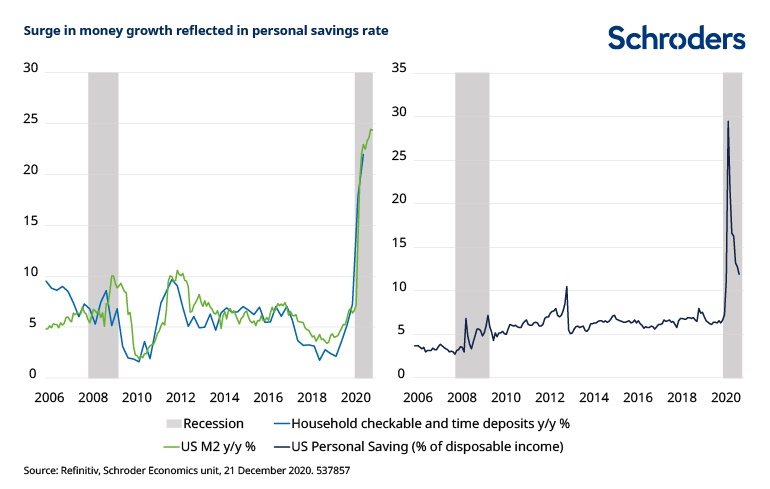

The second concern would be that the surge in money growth represents excess liquidity which will create a boom in spending once normal activity is resumed. Stronger demand will force prices higher.

While the correlation between money and activity is mixed, the recent strong growth represents a build up of deposits particularly in the household sector where spending has been suppressed. Corporate deposits have also risen, but household deposits closely track M2 growth over time with the recent surge driven by a build up in bank deposits. This has been reflected in the rise in the savings rate which remains elevated despite recent declines, as the chart below shows.

Although a rise in cash deposits is not unusual during a downturn, a rise of this scale has been unique to Covid-19. The key question is whether these deposits will be spent and if so, how rapidly?

It might seem that people will be keen to get back to normal and spend, but there could well be “scarring effects”. Households could take time to regain confidence. Some airlines have said they do not expect a return to normality until 2024, for example. Some spending patterns will change permanently as people choose to work from home more and commute less.

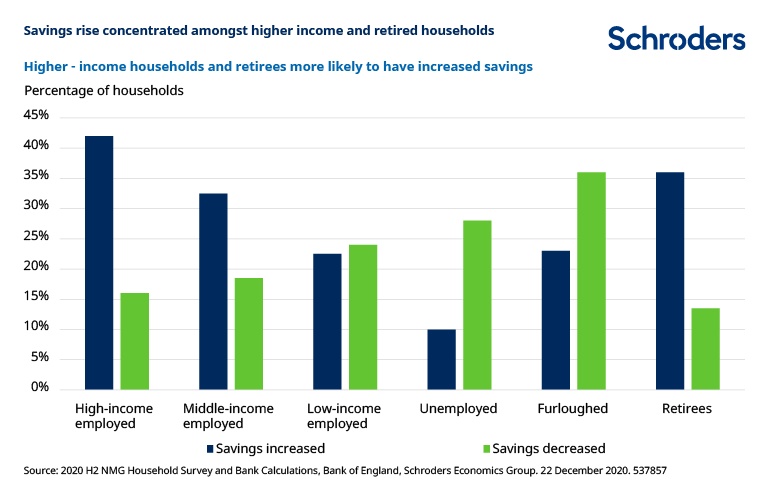

The rise in savings has been seen around the world, but has been concentrated amongst better-off workers and retirees. For example, a survey of UK households for the Bank of England found that the increase in savings during the pandemic has been concentrated amongst the top 20% of income earners and retirees.

Low income groups tended to slow or stop saving, while – not surprisingly – the unemployed and furloughed ran down their savings.

Higher income groups tend to save more and spend less at the margin and the survey bears this out. Only 10% of the households that increased their savings (less than 3% of the whole sample) plan to spend the money. About 70% said they planned to continue to hold the savings in their bank accounts. Others planned to use their savings to pay off debts, invest, or top up their pensions.

This does not rule out a bounce back in consumer spending as normalcy returns and households can stop building up savings and start to spend again. However, it does suggest that there will not be a strong bounce back from pent up demand. Those with the excess savings are likely to be cautious, which is consistent with other studies of spending after a pandemic.

Fiscal policy can help in this respect by targeting lower income households. Ultimately though, the excess savings or liquidity in the household sector is likely to dissipate gradually, thus putting less strain on the capacity of the economy and less pressure on inflation.

Route #3 – A supply side shock

The third concern is more long term and reflects the structural impact of Covid-19 on the economy.

Coming back to the scarring effects, if there are permanent changes to spending patterns as a result of the pandemic there will need to be a reallocation of resources. Workers will shift to the sectors which remain in demand. Such shifts are challenging. It may not be easy for a worker to re-skill for the new occupations. They may also have to become more mobile and move, which again can be a challenge for those with families and other ties.

The initial impact of this is deflationary as unemployment rises and can persist for some time. The inflationary threat comes later, when governments and central banks misread the high level of unemployment as being cyclical rather than structural. Excess monetary and fiscal stimulus can then create inflation as the economy’s supply capacity is not as great as the unemployment figures would suggest. The inflationary shocks of the 1970s had their origins in policy which did not recognise the adverse shifts in the supply side of the economy.

In this respect, the challenge from Covid-19- is not unique. Nonetheless, it is too early to make an assessment of whether it will lead to another major policy error.And this concern is certainly not the driver of the recent increase in inflation expectations in the financial markets. The same applies to fears over de-globalisation and the potential reconfiguration of supply chains post-covid.

In tracking these risks though, we would keep a close eye on wage growth and inflation expectations for signs that the relationship with unemployment is shifting.

Concerns are legitimate, but effects should be muted

Each of these three threats has some merit and the first where inflation is mis-measured is probably already with us. The greatest is the concern over money growth given the rise in liquidity and we would see this through the lens of higher savings. How people will react once they are immunised remains to be seen, but the survey evidence suggests we will see a measured response rather than a binge and higher prices.

Covid-19 has been particularly polarising in its economic effects on different income groups, such that it has concentrated the rise in liquidity and savings amongst the better off who will continue to save rather than spend. Markets will continue to worry, but the low rates for longer view should hold through 2021 and potentially beyond.