*This article was originally published by Fair Observer.

Hideaki Nakajima | The world was intended to be a better place when the international community pledged commitment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) after the relative success of the Millennium Development Goals that reached their target year in 2015. But there are expected to be highs and lows, as well as speed bumps, on the road to realizing a sustainable world through the SDG targets, set for 2030. The Future of Aid INGOs in 2030 report published by IARAN predicts growing challenges such as long and complex conflicts, widespread involuntary migration, violent natural disasters and rising inequality. The challenges faced by NGOs and the work cut out for them are unlikely to wind down any time soon.

A decade until 2030 looks like a long time, but not when the world is faced with crises on multiple fronts that require sustained action. IRIN, a website dedicated to covering humanitarian emergencies and aid, identifies 10 crises to watch in 2019, including “voluntary” returning of refugees, re-emergence of infectious diseases in countries experiencing humanitarian crises, anti-terror compliance imposed on NGOs, and continued militancy in Africa. These challenges have complex backgrounds and causes, but lack of political will plays a significant role when it comes to resolution.

Interlinked Challenges

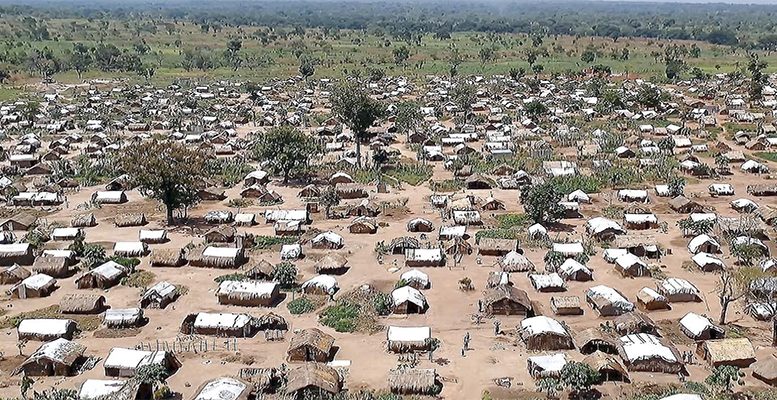

Pakistan has been putting pressure on Afghan refugees to return to their home country ravaged by war with the Taliban, having already repatriated more than 800,000 people since 2016. Bangladesh wants nearly a million of the Rohingya refugees to go back to Myanmar, where the ethnic minority faced a genocidal crackdown. It is a major concern that many of the repatriated people will only find their homes and land destroyed or confiscated. Returning refugees will have to rebuild their lives from scratch with already limited social services and security, or face looking for another country to accept them.

Meanwhile, in the Sahel region, weak governance is a major contributing factor to the ineffective fight against militants such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb; it is also the reason for the failure to win local support and discourage people from joining militant groups through provision of adequate social services. Against this backdrop, recipient countries enforce stringent “anti-terror” legislation and regulations on NGOs to deter distribution of aid that these governments designate as support for militants. Donor countries, on the other hand, want to strengthen tracking and regulations on NGO funding flows to make sure aid doesn’t end up in the hands of armed groups on the ground.

The challenges are all interlinked: People flee from countries mired in conflict and disease, but eventually find themselves involuntarily repatriated back to a home country that is politically and economically unstable, without adequate social or health services. Recipient countries that host refugees suspect them of being linked to militant groups like the Taliban, for example, using this as a justification for their repatriation and imposing regulations on NGOs working to help them.

In these circumstances, a lack of the international community’s concerted will and efforts to tackle these challenges is a concern. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) managed to collect just under 60% of the required funding from donors last year — $15 billion of the $25 billion needed. The trend of growing nationalism worldwide could be a factor. The isolationist policy of the Trump administration has seen a change from what has until recently been a major international moral leader and humanitarian donor — including the US withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement, narrowing its door to refugees and asylum seekers, and its budget cut for global reproductive health — is shameful.

Eurasia Group, a risk consulting firm, predicts political risks for 2019 such as lack of global leadership (“G-Zero”) and political volatility in the United States, a further rise of populism in Europe and a coalition against the global liberal order by countries such as Russia and Turkey. On the other hand, China’s global economic influence is strong when it comes to fragile economies. It is feared that these trends may exacerbate human rights in volatile aid recipient countries as the governments riding the trends become more negligent of protecting people’s rights.

A Lot to Worry About

The Future of Aid INGOs in 2030 report predicts four global scenarios affecting the future of aid. One likely scenario is the so-called “narrow gate,” in which the rise of nationalism will lead to a decline in the relevance of global governance institutions where the humanitarian ecosystem is challenged by the politicization of crises, particularly those in areas of chronic fragility. The report predicts an increase in control over and restrictions on humanitarian interventions; the growth of mistrust of NGOs regarded as West-centric; a struggle of finding a compromise between vision and values versus the necessity of accessing those in need; and a limited direct access to vulnerable communities, meaning a diminished position for international providers vis-à-vis local governments and NGOs.

All this indicates that suspicion toward NGOs at the political level, in which there is little room for mutual dialog and understanding, will risk leaving the voiceless and disempowered people behind. For example, across Africa, the decrease in the poverty rate is offset by the fact that more people are now living in extreme poverty, according to a 2016 World Bank report. Another worrying aspect of political intervention highlighted in The Future of Aid is more proactive participation in humanitarian activities by the military. This may further blur the lines between military and humanitarian actors, resulting in a perceived erosion of NGO neutrality, impartiality and independence, and a loss of access for nongovernmental actors to the victims of widespread abuses war and conflict, and, consequently, a diminished protection for civilians.

More proactive involvement of private military companies, which are not well regulated in international law, may also worsen the situation by raising the profile of NGOs and undermining their security. Aid may become less and less sustainable.

The Sustainable Development Goals must be achieved and their commitment safeguarded by concerted efforts by various stakeholders, including nongovernmental organizations. While NGOs may face internal and external pressures from tougher controls on funding and operations, they must be flexible to adapt to the changing situation and humanitarian ecosystem to be a viable actor. Where governments may be reluctant to safeguard human rights, it falls to NGOs to defend them, winning support and solidarity from civil society with goodwill.

The commitment of SDGs to “leaving no one behind” must always be at the core of advocacy, and NGOs must be part of it. Aid groups must keep making their voices and concerns heard. Though each cry may be quiet enough to be dispersed, concerted calls can become strong advocacy. There is still a tremendous amount of work to do.

*This article was originally published by Fair Observer.