*This post has been originally published in the blog Sparse Thoughts Of A Gloomy European Economist.

Francesco Saraceno | The crisis is supposedly over, as the European economy started growing again. There will be time to assess whether we are really out of the wood, or whether there is still some slack. But this matters little to those who, as soon as things got slightly better, turned to their old obsession: DEBT! Bear in mind, not private debt, that seems to have disappeared from the radars. No, what seems to keep policy makers and pundits awake at night is ugly public debt, the source of all troubles (past, present and future).

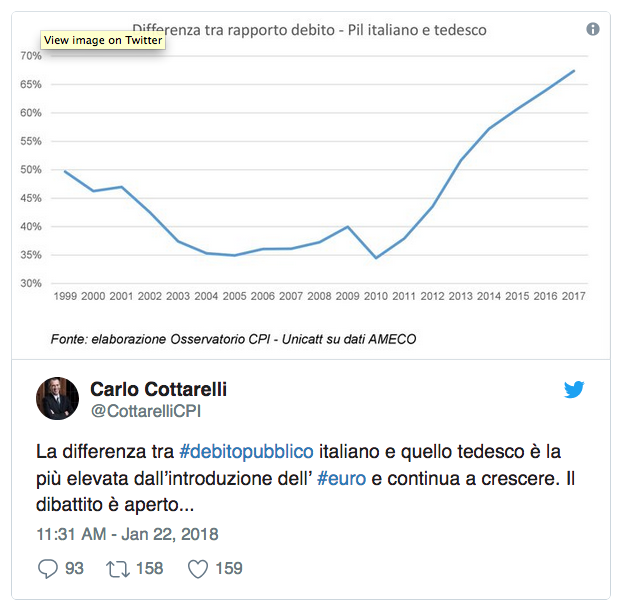

Take my country, Italy. A few days ago this tweet showing the difference between the Italian and the German debt made a few headlines:

The ratio increased, so DEBT is the Italian most pressing problem. Not the slack in the labour market. Not the differentials in productivity. I can’t stop asking: why aren’t Italians desperately tweeting this figure?

This shows the relative performance of Italy and Germany along two very common measures of productivity, Multifactor productivity and GDP per capita. I took these variables (quick and dirt from the OECD site), but any other measure of real performance would have depicted a similar picture.

So what? The public debt crusaders will argue that precisely because of debt, Italy has poor real performance. The profligate public sector prevented virtuous market adjustments, and hampered real convergence. The causality goes from high debt to poor real performance, they will argue. Reduce debt!

Well, think again. Research is much more nuanced on this. A paper by Pescatori and coauthors shows for example that countries with high public debt exhibit high GDP volatility, but not necessarily lower growth rates. High but stable levels of debt are less harmful than low but increasing ones. In a recent Fiscal Monitor the IMF has shifted the focus back to private debt (which, it is worth remembering is the root cause of the crisis), arguing that the deleveraging that will necessarily continue in the next few years will require accompanying measures from the public sector: on one side, renewed attention to the financial sector, to make sure that liquidity problems of firms, but also of financial institutions) do not degenerate into solvency problems. On the other side, the macroeconomic consequences of deleveraging, most notably the increase of savings and the reduction of private expenditure, may need to be compensated by Keynesian support to aggregate demand, thus implying that public debt may temporarily increase in order to sustain growth (self promotion: the preceding paragraph is taken from my book on the relevance of the history of thought to understand current controversies. French version available, Italian version coming out in March, English version coming out eventually).

In just a sentence, the causal link between high debt and low growth is far from being uncontroversial.

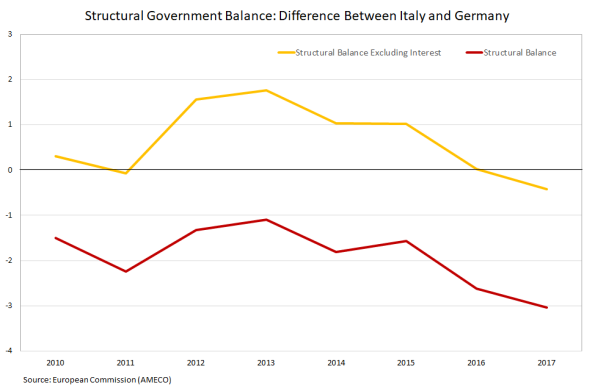

Last, but not least, it is worth remembering that Italy was not profligate during the crisis; unfortunately, I would add. Let’s look at structural deficit (since 2010; ask the Commission why we don’t have the data for earlier years), which as we know washes away the impact of cyclical factors on public finances.

The Italian figures were slightly worse than the German ones, but not dramatically so. And if we take interest expenditure away, so that we have a measure of what the Italian government could actually control, then Italy was more rigorous (Debt obsessive pundits would use the term “virtuous”) than Germany.

The thing is that the Italian debt ratio is more or less stable, in spite of sluggish growth (current and potential) and low inflation. It is not an issue that should worry our policy makers, who should instead really try to boost productivity and growth. Said it differently, it is more urgent for Italy to work on increasing the denominator of the ratio between debt and GDP than to focus on the numerator. And I think this may actually require more public expenditure and a temporary increase in debt (some help from the rest of the EMU, starting from Germany, would not hurt). It is a pity that the “Italian debt problem” is all over the place.