Romain Boscher (Fidelity International) | Former US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan is famed for describing booming markets during the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s as “irrational exuberance”. A generation later, this concept is back with a twist, and, as it happens, fuelled by the US central bank itself.

This is closely related to another concept associated with Greenspan – the ‘Fed Put’, which was first coined during the 1987 stock market crash but gained renewed prominence under his successor Ben Bernanke. During the Bernanke era it implied a safety net where the central bank would purchase government bonds at high prices in order to lower the Fed Funds rate.

Today, major central banks around the world are buying a whole range of assets at an almost unfathomable scale. A similar level of amplified spending can be observed on the fiscal side, where growing budget deficits have in some cases have more than offset the impact of the Covid-19 related recession. One example is the many unemployed Americans who have seen their income rise during lockdown, exceeding their previous work income.

From ZIRP to FOMO to TINA: the drivers of the K-shaped recovery

We are facing a bizarre situation where conventional economic thinking cannot explain many of the prevailing trends: zero and negative interest rate policies (ZIRP, NIRP), growing disposable incomes and rising trade deficits during recession, and all-time market highs occurring as earnings contract by record margins. Some of these events are temporary while others will be longer lasting, but they are generally unprecedented and counterintuitive.

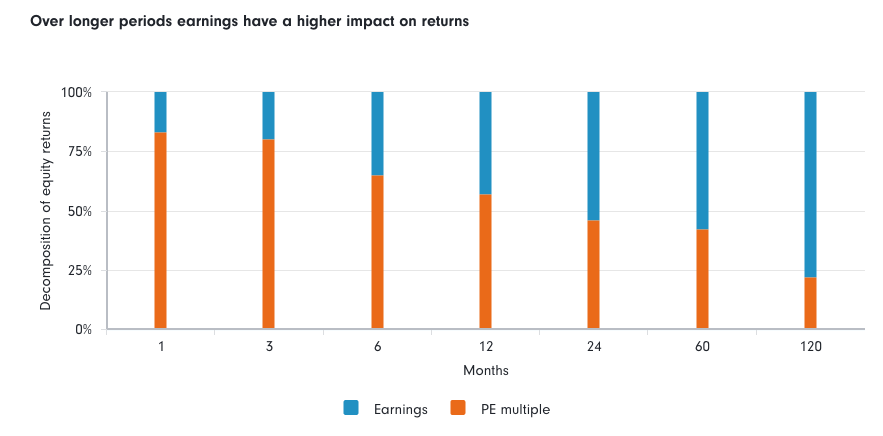

This bull market coinciding with falling earnings has been made possible by the zero-rate environment that is driving up valuations. Investors are joining the headlong rush to profit from the rising market out of the fear of missing out (FOMO), and, with bond yields so low, many investors believe there is no alternative (TINA) to allocating to stocks. These are the key defining parameters of this market and they are likely to remain so for some time.

At the risk of overwhelming you with acronyms and letters, some think an ‘M-shaped’ recovery is playing out where momentum is driving a sharp rebound. In contrast, I believe there will be two distinct outcomes; those that do well out of Covid-19 and those that fare badly, dubbed the ‘K-shaped’ recovery.

Covid-19 winners and losers

As investors gradually look beyond the veneer of fiscal and monetary intervention, the underlying currents will become much more pronounced.

Recessions are remarkable agents of change, completely reversing trends or fast forwarding them. Prior to this crisis digitisation was already a force, but it has now rapidly gathered pace. There are companies that are benefitting two-fold from digitisation; firstly by having the infrastructure already in place to absorb additional demand (for example companies with access to cloud storage that can easily flex capacity) and secondly by falling costs such as lower travel and entertainment expenses or gaining efficiencies from optimising location agnostic set-ups.

At the other end of the spectrum there are those companies with business models designed for the ‘old world’: bricks and mortar shopping outlets, fossil fuel companies, banks with near-obsolete branches, and the list goes on. This catalogue of superseded companies explains why there is such a large divergence in valuations in the market. It is more than just a simple growth versus value debate – it is a generational shift between an old and new world.

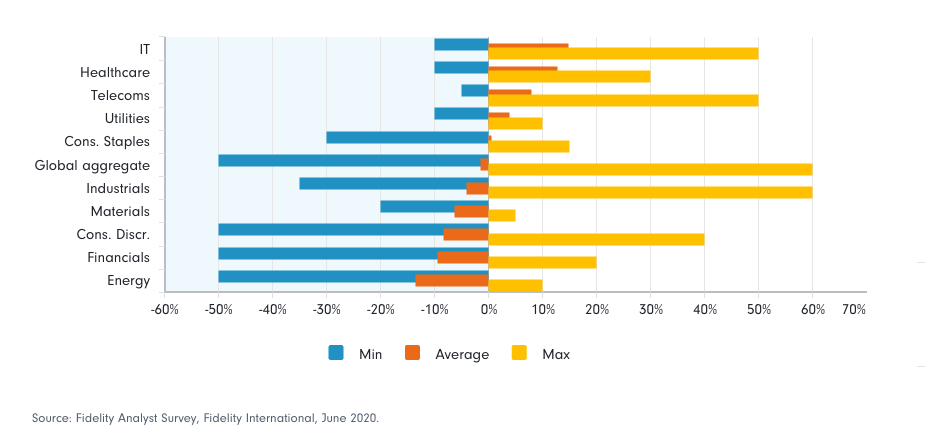

Wide divergence in outcomes within and across sectors

Answers to: “How do you expect full year 2021 earnings to compare to full year 2019 earnings?”

Valuation discrimination will return

In an environment of low economic growth and yield, capital competes for growth and income exposure. Those characteristics are becoming increasingly scarce and this is likely to continue, further driving investors to, quite rationally, seek growth and income-oriented names, sometimes at dizzying valuations.

As the virus outbreak demonstrates the vulnerabilities of companies and industries, many of these investors are now applying a quality overlay in their stock selection. Companies highly rated for sustainability often tick the requisite boxes. These companies are in the business of pursuing sustainable growth, which can be effectively boiled down to a combination of quality and growth factors.

But the stark issue is valuation. These sustainable growth companies undoubtedly present strong financial profiles but investors are buying them at almost any price. As a K-shaped outcome starts to exert itself – this time in expected returns – I anticipate valuation discrimination to come back into focus. In the short-term, abundant liquidity will whipsaw markets, but earnings will be the yardstick to measure performance in the long-term.

The K-shaped scenario is also valid for value stocks – companies that sell at low multiples and are currently at historically large discounts to growth names. Two groups are emerging within the value bucket: those that will struggle to survive and those that can thrive. Fossil fuel companies and banks with significant high street presence are losing relevance and in terminal decline. Industrial companies, durable goods producers and even some low-cost airlines could potentially surprise investors in their recoveries, particularly with the tailwinds of accommodative fiscal and monetary policies. Fiscal support will help repair Covid-19-inflicted damage to the economy while monetary easing will lubricate the market to climb higher.

It’s 24 years since the term “irrational exuberance” was first coined and, while I haven’t quite exhausted all 26 letters of the alphabet in acronyms and novel descriptions of the recovery, what we are experiencing is within the bounds of rationality – albeit an exaggerated form of it.