So, the first conclusion is that the Fund is systematically underestimating the Spanish recovery. Seven tenths of a full percentage point are a significant correction, but even more so when that is the distance from 0.2 percent to 0.9 percent growth.

In the Fund’s defense, it must be said that making predictions is not easy. The late John Kenneth Galbraith quipped that, “the only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.” And the IMF is not the only organization that struggles with forecasting the future. This past week, the Spanish Finance Minister, Luis de Guindos, scaled back the Government’s official inflation forecast in 2014 to 0.5 percent, that is, just one third of the 1.5 percent it had established in late September.

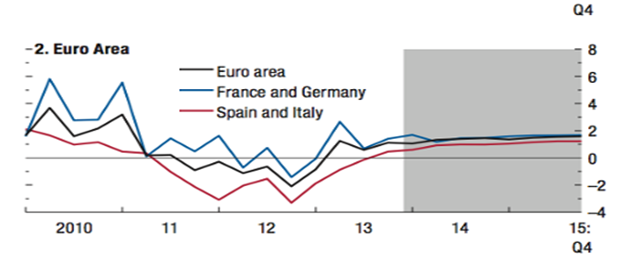

However, there are signs that prove that the IMF, once again, could be underestimating the strength of the recovery in Spain.

Currently, Spain is experiencing a small deflation. This, in itself, is worrisome, but, as long as the economic agents incorporate it into their expectations, it is not necessarily bad in itself. Temporary deflation—or, in the IMF’s parlance, ‘lowflation’—allows the government to spend more without pushing the prices or even deteriorating the fiscal deficit.

Currently, the Spanish government (and, particularly, the regional governments) is not restraining its spending, and that trend it is going to continue. Add to that higher tax receipts—through the VAT and the Income Tax, thanks to the slow recovery—and less unemployment benefits—due to the stabilization of the labor market—and there is no reason for Spanish authorities (at a national or regional level) to put another adjustment into practice.

More relaxed government spending can easily add 1.3-1.5 percentage points to the quarter-to-quarter GDP. If, in the fourth quarter of 2013, in the midst of a drastic restraint of government spending, Spain’s GDP grew by 0.17 percent, this means easily 0.3 percent of growth.

Government is not the only GDP factor that could push more than the IMF expects. The adjustment of the housing prices is helping tourism, a very important component of the Spanish GDP. And there are multiple signs that prove that the consumer and business sentiments are, slowly but surely, improving. Again, as long as the deflation is not incorporated to the expectations, that means higher consumption and investment.

This does not imply a sudden recovery, but sets the stage for a 0.3 percent to 0.5 percent quarter-to-quarter GDP growth which, in turn, would mean around 1.2 to 1.5 percent annual rate. Given that the current Spanish Administration is going to cut taxes—with the eyes put in the elections of late 2015 or early 2016, next year growth would be close to 2 percent. That would mean doubling the IMF forecast.

So, is the crisis over?

Not at all. First, note that this forecast is based upon one assumption: the Spanish government is not going to continue the adjustment in its spending, and the regional governments are going, probably, to hire more people and spend more. That means that the restructuring of the government sector is being, once again, postponed, either for 2016 or 2017—after the elections—or until the next big crisis strikes again. Not a comforting message in the long run, but, as Keynes famously said, “in the long run, we will be all dead”.

Be the first to comment on "Why Spain could grow half a point more than what the IMF says"