BoAML Research | One reason the Federal Reserve has been so dovish recently has been a lack of conviction in wage and price inflation. Fed Chair Janet Yellen ’ s speech earlier this week confirmed that she is not convinced that the recent rise in core inflation would “ prove durable ” and stated that more adverse -than -expected foreign developments could slow the pace of labor market improvement, and with it, “ growth in both wages and prices. ” Last week, we argued that the pickup in core inflation was likely to prove mostly persistent, despite Yellen ’ s skepticism. This week, we take a look at the wage side of the outlook. At her mid -March press conference, Yellen stated that “ in the aggregate data, one doesn’t yet see any convincing evidence of a pickup in wage growth. ” However, we argue here that many distinct measures of wages have tilted higher. In addition, while Yellen suggested wage increases were “ mainly isolated to certain sectors and occupations, ” we see increases across a relatively broad cross -section of the market. That said, although the ugly years of steady 2% nominal wage growth may be behind us, the pickup has been and likely will continue to be gradual.

In the aggregate

There are several common measures of aggregate wage growth for the US. Yellen ’ s assessment notwithstanding, the general sense one gets from the most commonly cited series is that wages finally started to pick up last year:

- Arguably the best measure is the employment cost index (ECI). As a measure of total compensation, it spiked briefly last year but has since fallen back to its six-year trend.

Stripping out benefits, the upturn in wages and salaries growth is more convincing. Firms appear to be shifting benefit costs onto their workers as wages pick up.

- Total average hourly earnings (AHE) ran around a 2% yoy pace for the past six years before peaking above 2.6% last December. It has since slipped back some, rising 2.3% yoy in the most recent March employment report.

- About 80% of the total AHE measure is production and non-supervisory workers. It has followed a similar pattern as the total, but the upturn had been more compelling: this series bottomed at 1.3% yoy in 2012 and has been on a choppy trend higher since. It also rose 2.3% yoy in March.

Wage growth has also accelerated for two more volatile series. Median usual weekly earnings (MWE) has been trending up the past few years and recently peaked at 3.3% for 4Q 2015. Compensation per hour (CPH) from the nonfarm business productivity data is currently running slightly above its prior six-year average growth rate.

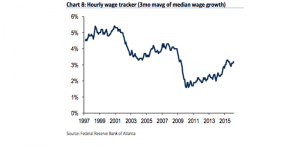

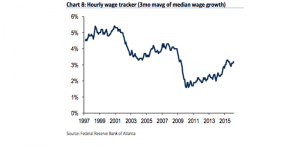

Another measure of note is the Atlanta Fed’s “wage growth tracker (WGT)”. This measure tracks how hourly earnings have changed for individual workers over a rolling 12- month interval, based on a sample from the Current Population Survey. Note that by tracking wage changes for individuals over time, this measure should be a more accurate representation of actual wage growth versus comparing the median wage earner at one point in time with the median wage earner 12 months earlier — these are almost certainly going to be different people in each period. On the other hand, the requirement that a person must be in the sample for 12 months straight will exclude some temporary and other workers (such as new entrants and re- entrants) and thus may give an upwardly biased estimate of the true median wage change. However, looking at how this series has changed over time, figure below also shows evidence of an increasing trend rate of wage growth over the past year or two.

Aggregating up from individual worker data also allows one to estimate what share of workers are receiving zero annual wage increases, a measure that the San Francisco Fed has tracked since the late 1990s. It had averaged 11 to 12% going into the recession, rose to 16 to 17% at its peak from 2011 through 2013, and has started to slip back down to 14 to 15% in the past year or so — similar to the share seen in the mid-2000s.

Cross-sectional comeback

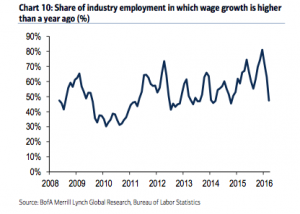

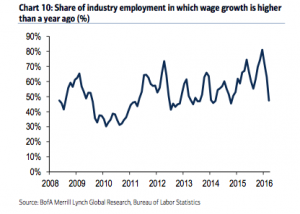

One criticism of these aggregate and other measures is that the increases have only occurred in a few sectors or industries, or have been concentrated at the lower end of the skill and pay distribution. A closer look at the disaggregated data suggests limited support for this view, however. Next figure shows the share of industry level employment in which 12-month wage growth is higher than it was a year ago. (We then take a three- month moving average to smooth out the high-frequency volatility.) After an initial spurt of wage growth in 2011 and 2012, the share of industries experiencing accelerating wages did dip below 50% frequently between mid-2012 and late 2014. Since early 2015, the share has been fairly consistently in a 60 to 70% range.

The Atlanta Fed’s WGT also allows for the data to be split between services and goods, or between high-skill (proxied by workers with a college degree) and other workers. Neither of these divisions suggests a sharp divergence in wage growth along these characteristics, implying the observed increase is relatively broad-based. There is some evidence in the WGT that wage growth has been slightly higher for full-time versus part-time workers, and this is consistent with other reported evidence on the gap between the two. The share of part-time workers remains elevated, but has fallen sharply over the past few years; that shift may also help account for some of the more recent gains in aggregate wages as an increasing share of workers are in full-time employment with on average faster wage growth.

The benefits of higher wages

Stepping back, despite Yellen’s skepticism, we see evidence of sustained and broad- based wage gains. Such an improvement is important for a number of reasons. First, it suggests that inflation also should continue to improve. Fed officials have cautioned that the link between wage and price growth is not strong, and we would agree. However, over time the two do tend to co-move together, and all else equal, higher wage growth is supportive of progress toward the Fed’s inflation target. In addition, higher wages also suggest that the remaining slack in the labor market is diminishing — which should lend further support to the inflation outlook.

More importantly, higher wages are essential to continuing the growth in consumer spending that has largely supported the recovery to date. Rising employment and hours have helped boost household incomes even though wage growth remained tepid; as the recovery advances some acceleration in wage growth is the next piece to contribute. Additionally, the low level of nominal wage growth had been offset by falling energy prices, supporting real wages. As energy prices post a modest rebound and inflation moves up, higher nominal wage growth will be necessary to keep real incomes and spending growing.

One concern with higher wages is the impact on firm’s profits. It is true that an increase in wages will, all else equal, increase the costs to firms. Wage increases that reflect higher productivity need not reduce profits, but labor productivity has been quite low of late. Rather, higher wages currently follow a protracted period in which business’s share of national income had increased at the expense of labor. But if higher wages help to boost aggregate demand, profits need not fall and could even improve. Our Equity Strategists have argued that there is little relation between wages and S&P 500 profits. When we look at the correlation between industry-level profit growth and wage growth since 2007, we find a small negative value, although there is a fair bit of heterogeneity across industries and the sample is not long. And with profits still at historically high shares of GDP, some modest shift to higher wages should be a net stimulus to spending overall, and thus growth. With the recent slowdown in GDP growth estimates, rising wages would be a welcome sign.