Jared Franz & Lisa Thompson ( Capital Group) | You might think where someone decides to buy their coffee in the morning doesn’t amount to a hill of beans when it comes to the health of the U.S. economy. But, in fact, it could mean a great deal in the years ahead.

“Working remotely for the past year and a half, I’ve been buying coffee closer to home instead of my usual downtown coffee shop,” says Capital Group economist Jared Franz. “In my case, it doesn’t mean much, but if a quarter of the U.S. labor force does it one or two days a week, it has significant implications for the economy, financial markets and the future of large cities.”

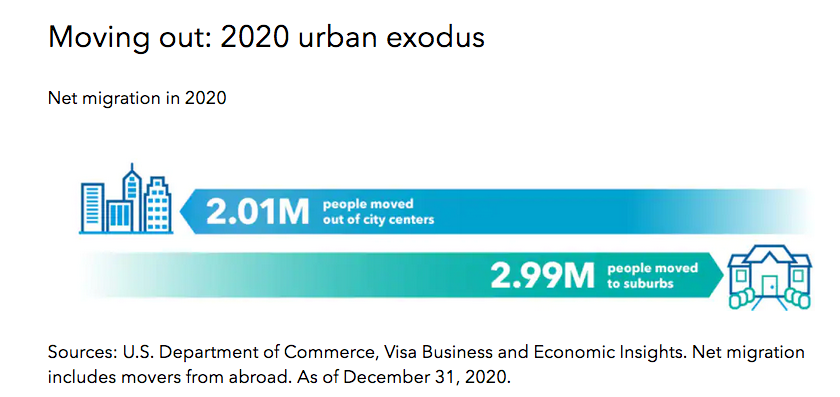

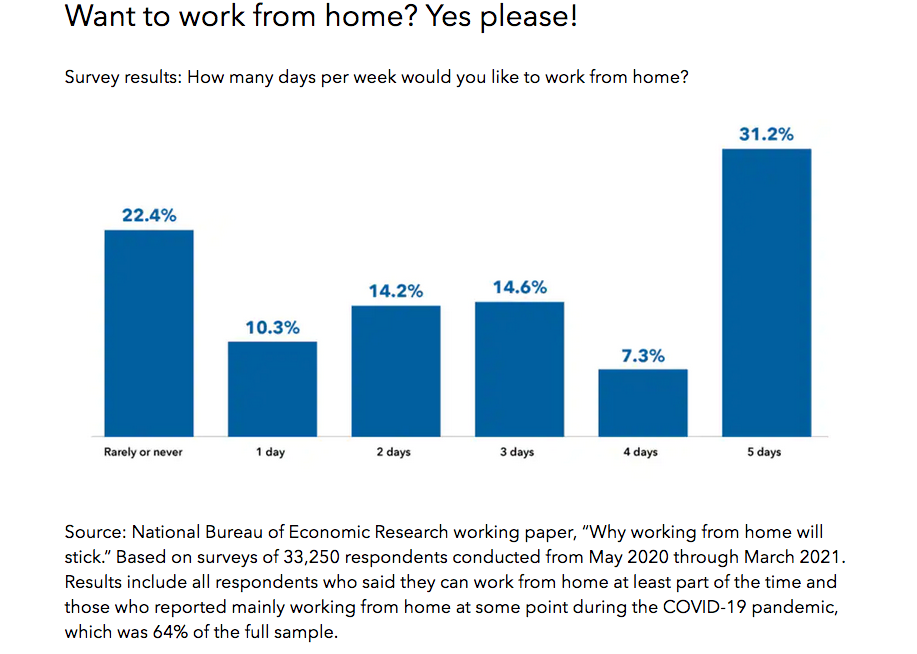

While the data is short term and the jury is still out, there are early signs of a powerful deurbanization trend in the United States and other major developed economies. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, migration from some big cities has accelerated while suburban home prices have soared. Moreover, national labor force surveys indicate an overwhelming majority of employees who have been working from home want to continue doing so one or more days per week.

By 2022, Franz estimates, roughly 25% of U.S. employees could be working remotely — up from just 5% prior to the pandemic — and many of them will choose to live in less expensive, less crowded areas. Assuming this shift persists, it would be the biggest change in US labor-force patterns since World War II.

“From an investment perspective, we need to determine how durable these changes are, how they could affect consumer spending patterns and how companies may respond,” Franz explains. “For instance, what happens to that downtown coffee shop? Or the restaurants that serve the same area? Or the office space that is no longer needed?”

“I don’t think we are talking about the death of big cities, by any means,” Franz stresses. “But I do think we may have reached peak density for urban centers such as Chicago, Los Angeles, New York and San Francisco. They will have to adapt to a world where much of the labor force is no longer coming into an office every day. Twenty-five percent may not sound like much, but it’s a huge incremental change from 5%.”

Many important questions remain unanswered: Will people flock back to big cities after the pandemic is over? Will they prefer life in the suburbs and other outlying areas? Or will both happen at the same time — perhaps with younger employees preferring to live in vibrant, dynamic cities and older workers continuing to fuel the growth of the suburbs?

One crucial question appears to be resolved: People like working from home.

Sectors that benefit from deurbanization

Many sectors stand to benefit if the deurbanization trend endures, including personal travel and leisure, technology and communications, cloud computing, and the home improvement industry and residential real estate — particularly in the suburbs and other outlying areas.

Changes in consumer behavior mean these trends could be durable even as we head back to the office several days a week. For example, home improvement stores such as Home Depot have clearly benefited from more people buying new and existing homes in the suburbs while the shift toward home fitness has boosted companies such as Peloton and Nike.

Exercise and outdoor activities are a potential bright spot, says Capital Group portfolio manager Lisa Thompson. “As an investment theme, I think it’s almost metaphoric. People are spending more time in nature, hiking or riding bikes, and they are realizing it’s actually very nice to be outdoors, to spend more time with family, to visit the national parks. I have friends who go camping now I never imagined would go camping.”

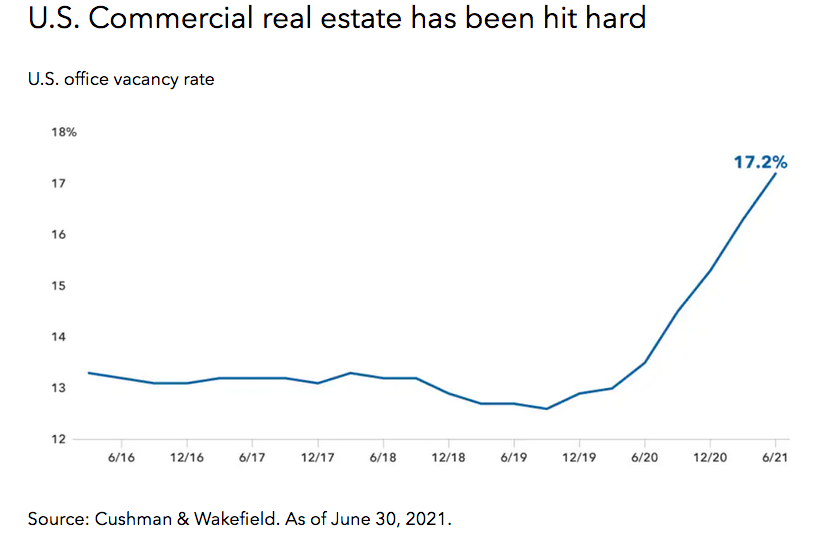

Coomercial real estate loans, menawhile, have not experienced the type of distress or outright defaults that investors might expect, largely due to government stimulus programs that helped small and mid-size companies meet their lease and payroll obligations. “We are in a holding pattern right now because government support has been so strong,” Franz notes, “but as we move into 2022, I think that could change materially for the worse.”

Within the wider real estate industry there has been a large disparity between subsectors that have been hammered — office, retail and hotel, for instance — and others that have rallied as the economy and stock markets recovered from the downturn. Those include storage, industrial and residential categories.

In states with large urban centers, state and local government finances could also be impacted, Thompson adds.

“Deurbanization puts a lot of pressure on states like New York and California that have relied on a very high tax base of wealthy people in Manhattan, Los Angeles and San Francisco,” Thompson notes. “It could wind up being a big challenge for states that have benefited enormously from the mega-city concept.”

Echoing Franz’s sentiment, however, Thompson says she expects large urban centers to adapt and eventually thrive in a post-COVID environment. Big cities are resilient, she says, and they have a long history of recovering from difficult times.

“I can remember when big cities were not places that people wanted to go in the 1970s and 1980s,” Thompson recalls. “Today, older people may say, ‘I don’t need to be in the city anymore,’ but I think younger people will still want to be at the center of civic life and entertainment. Cities will just reinvent themselves again.”