With the end of year in sight, there are three main questions raised by the economic situation in emerging Europe. The first, and surely the most fundamental, is whether the deterioration in activity touched bottom in the third quarter. In order to answer this question properly we will also have to determine what is happening in Poland. This trio of questions of the moment is completed by the doubt whether Hungary will soon reach an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

With regard to the question of whether activity touched bottom in the third quarter, far from having been clarified with the publication of the national accounts data for the quarter, this diagnosis of the cyclical position is even more complicated. We should remember that, in this period and in line with preliminary estimates, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania declined in quarter-on-quarter terms (-0.3%, -0.2% and -0.5%, respectively). The exception to this quarterly negative trend was, once again, Slovakia, which posted quarter-on-quarter growth of 0.6%. For Poland, which we will return to, there are still no figures on the change in GDP for the third quarter.

This view doesn’t change appreciably in year-on-year terms either. The extent of the year-on-year drop is practically identical in the Czech Republic and Hungary, standing within the zone of -1.5%, and slightly lower in Romania (a year-on-year drop of 0.8%). Slovakia, for its part, has posted two consecutive quarters of around 2.5% growth year- on-year. Although we still don’t have the details on the components, the available monthly indicators point, in all cases, to the cause being a combination of falling domestic demand and exports that are suffering significantly from the slump in the central markets of the euro area, which has hindered growth.

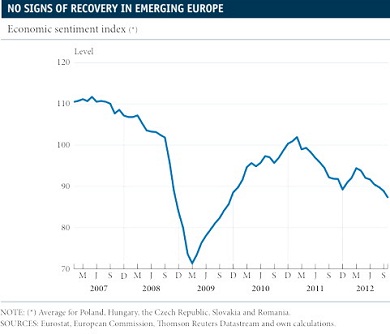

Based on this development, what can we expect in the coming quarters? First of all, we should remember that the figures for the third quarter were slightly worse than expected in general terms. Then we must add to this moderately worse than expected starting position the fact that the euro area, which entered recession in the third quarter, is expected to see a further decline in activity in the fourth quarter. Lastly, we should also note that the trend in economic sentiment, as can be seen in the graph below, points to the rate of activity continuing to fall. All this confirms a scenario in which activity did not touch bottom in the third quarter but, with a bit of luck, might do so in the fourth.

The fundamental regional element that will determine whether this scenario comes about is how Poland develops. In order to evaluate this, we must look at the second of the questions mentioned at the beginning of this section, namely what is happening in this country. In summary, the answer is that, after several years of Poland’s economy, the largest in emerging Europe, standing out positively in the whole of the European Union (EU), since the second quarter of 2012 it has recorded a notable slowdown. The main factor behind this deterioration is the loss of dynamism in domestic demand, a circumstance that, in turn, can be explained by a combination of factors. Firstly, after several years of delaying what budget orthodoxy would have recommended, in 2012 fiscal policy has started to become more restrictive. After a certain amount of fiscal profligacy that can be partly associated with events such as the European Football Championships this year, the government has started to moderate its rate of spending and investment in an attempt to stop public debt breaking through the legal limit of 55% of GDP.

A second factor is that other trends that have been occurring for some time now, such as increasingly contained corporate earnings or a certain decline in the labour market, have intensified. Given the inertia that characterizes domestic demand, we predict this slowdown to continue in the fourth quarter with no change being expected until early 2013. Given this situation, it’s understandable that Poland’s central bank has reduced its reference interest rate by 25 basis points to 4.5%. This movement represents the start of a cycle that will more than likely continue in 2013.

Lastly, the third question we asked is whether Hungary will shortly access international financial aid, fundamentally orchestrated by the IMF and the EU. As will be remembered, the reason underlying the application for multilateral financial aid, made one year ago at the time of writing, was the need to increase the country’s margin for financial manoeuvres to meet its external obligations at a reasonable cost. Unlike the previous programme, in 2008, in this case there’s no pressing problem of liquidity.

To this end, the executive is attempting to obtain some kind of precautionary aid that will boost the country’s financial capacity, reducing the cost of its external financing for a time. After various ups and downs in the negotiations, and although Hungary has adopted a sufficiently restrictive Budget for 2013 to move away from a situation of excessive deficit, the little orthodoxy of some of its fiscal measures (including a tax on bank activities and operations) has led to disagreement between the country’s political authorities and international institutions. Within a global context of falling risk aversion and with the euro area crisis appearing to move away from its peak of financial stress, in our opinion there are limited incentives for an immediate agreement. That’s why we tend to believe that this issue might remain at its current impasse until well into 2013.

Be the first to comment on "Emerging Europe is no brighter spot"