As almost all European governments are cutting spending, it is hardly a surprise that the EU’s budget is under fire. The European Commission has rather optimistically proposed a real terms increase of five per cent in total spending over the next budget period, which runs from 2014 to 2020. This amounts to 1.05 per cent of projected EU GDP over that period. But most of the countries that pay more into the budget than they get back reject this proposal.

Germany and Ireland want the budget limited to one per cent of EU GDP (which means that as Europe’s economies grow, the budget can grow too, but at a slower rate than the Commission wants). However, British Prime Minister David Cameron wants to go further: he has promised to veto anything but a freeze in real terms. It may be difficult to back down from this position in budget negotiations: the opposition Labour party combined with backbench Conservative rebels to win a parliamentary vote last week that called for a cut to the budget, defeating the government. Cameron would be unlikely to get a larger EU budget through the UK’s parliament if he compromises at the summit, on November 22.

Britain is not the only budget hawk: Sweden and the Netherlands have also demanded big cuts to the Commission’s proposal. But neither has demanded a freeze.

How much does the UK currently pay, and how much does it receive? As a comparatively rich country with a small agricultural sector, the UK has in recent years been a net contributor to the EU budget. The UK passes tax revenue to Brussels, and receives less expenditure in the form of Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) payments, regional development funds, and other transfers in return. But it has a rebate from Brussels–a reduction in its contributions negotiated by Margaret Thatcher in 1984, which many other EU countries consider to be unfair now that Britain is one of the richer members of the club.

Given that any country can veto the EU budget, member-states must build alliances to succeed. The UK is isolated after its veto of the fiscal treaty, and so would do well to be cautious if it wants to reduce spending. Britain wants the budget frozen at its 2011 level. But if the talks collapse, which is a distinct possibility, the 2013 budget will simply be rolled over to 2014, but with inflation added. The budget would end up far larger than 2011.

If the UK really wanted to cut wasteful spending and promote growth, it could accept the German proposal for a budget capped at one per cent of EU GDP, in exchange for cuts to the CAP and a transfer of that money into infrastructure and regional development spending. France has threatened to veto any budget that does so, but they could be isolated if Britain were prepared to make concessions.

But such a deal may be difficult for Cameron, who has chosen to make budget cuts his priority. The UK’s net contribution grew by three-quarters between 2006 and 2012, from £3.9 billion to £7.4 billion (€4.8 to €9.2 billion). The UK’s transfers to Brussels were low in 2008 and 2009 because it suffered a larger recession than other member-states, and in 2010 and 2011 payments were larger because its economy made a (small) recovery. On the expenditure side of the ledger, European Social Fund and Regional Development Fund spending in the UK is falling over time. These funds provide support for struggling regions with an income less than three-quarters of the EU average. Over the course of the last budget, Brussels has phased in the poorer newer members in Central and Eastern Europe, so that a greater proportion of structural funds go to these countries. These two factors explain most of the rise in the UK’s net contribution.

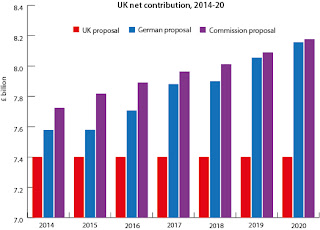

The UK government’s position implies a continued UK net contribution of around £7.4 billion (€9.2 billion). The German government’s proposal would mean the UK paying slightly more – an average of £400 million (€499 million) a year over the budget period. The Commission’s proposal would see the UK contribution grow, in tandem with Europe’s economic growth. So, under the Commission’s proposal, the UK’s net contribution would grow from £7.4 to £8.2 billion (€9.1 to €10.2 billion), an average of £550 million per year (€690 million) higher than under the UK proposal. This would mean a total increase, above the UK’s proposal, of £3.9 billion (€4.8 billion) over the seven years.

These numbers are difficult to appraise without context. Under either Germany’s proposal, or the Commission’s, the UK could end up paying around £400 and £550 million per year more, at most. This is around 0.03 per cent of GDP. It is the same amount that England and Wales spend each year on flood and coastal defences, or the same size as Oxfordshire County Council’s budget.

If Cameron brought down the negotiations over such a small sum, the UK would find itself pressed further into the margins of Europe. It would do better to compromise on the overall size of the budget, and negotiate for it to be spent more wisely.

Be the first to comment on "Cameron’s stubbornness in Brussels will be expensive for the UK"