Which is the problem that Pilkington raises for the monetary policy to achieve its goals? Simply , the financial sector, which is not so “obedient” to the ECB’s objectives. The disagreement during present crisis between the monetary base, which is the only the central bank can control, and the monetary offer, comprising cash and non- cash payment instruments created by banks, are those deposits capable of being mobilized by means of cheques and credit cards.

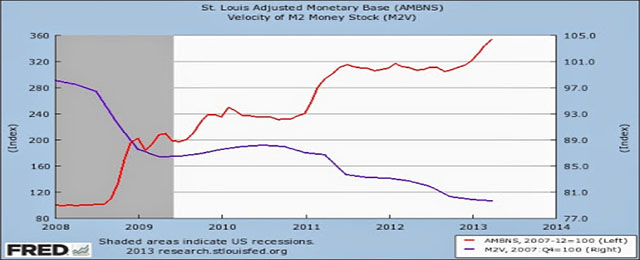

Do you remember the picture above? The red line is the monetary base, and the blue one is the speed of money supply (M2) circulation. So, the QE’s marginal efficiency to mobilise money is very short. The reason: between B and M2 is the credit, a rate currently spurned, but which has its own causes as proved by the picture. An increase of B does not always involve an increase of M2.

The following is Harrod’s contribution to this point: financial market is not perfect, especially for most of borrowers who are rejected just when the need of this credit is more nagging. Here I reproduce his transparent words:

“It must be remembered that the capital market is for most people an imperfect one. There are bits of the capital market which function in the way of perfect markets, where at any one moment there is a going price at which the individual (other than some giants, like the government broker) can satisfy his needs. Such are the gilt-edged end of the stock exchange [i.e. stocks for state-backed, nationalised industries] and the discount market. But most borrowing for capital outlay is not done in these markets.

There are all the various channels for borrowing, the commercial banks themselves, the market for new issues, financial syndicates, insurance companies and, above all, trade credit, which plays a vital role. In these various markets it is not a question of just taking out as much money as one wants at the going price. It is a question of negotiation. When the aggregate money supply is reduced, a would-be borrower may find it more difficult, and even impossible, to raise money through his accustomed channels; and conversely. It is essentially the imperfection of the capital market that makes monetary policy a powerful weapon. (pp64-65).”

Of course, the Fed’s monetary policy is a benchmark floor for the financial activity’s contraction and also deflation. This explains why the economy has not fallen into a deep chasm similar to that of 1929, in which prices dropped by 30% in three years. However, the monetary push coming from above could reach the most needed borrowers just in the case other variables, such as risk valuation, do not change too much.

In normal times, risk valuation is stable. This allows to translate the monetary policy much more directly. Neverthesless, in times of euphoria like the pre-bubble context, risk valuation decreases a lot and credit rockets. Subprime mortgages are the best example of accelerated credit. In times of crisis, the risk valuation goes to the other endpoint and the transference slows down. The bad debt and the deflation increase the prudence. The bad point is that the risk valuation is not easy to be measured.

One of the signs to determine where exactly Spain is regarding this point are the interest rates for banks’s private customers against their European counterparts. Next picture, courtesy of Juan Carlos Barba, shows the turning point of interest rates in Spain is slower than in Europe; its gap grows over two percentage points.

All this means that the EZ’s asymmetry has increased, making the ECB’s policies even more difficult. However, the credit contracts in the entire euro zone with Draghi saying that he is concerned about deflation.

All euro area countries, except Germany, need credit expansion. It is convenient to have a supporting policy that weakens the appetite for risk in times of euphoria, and also the opposite: stimulate it. Now people talk about “macroprudencial policy” to control credit expansion. But this is not easy.

Be the first to comment on "To control credit expansion is tricky"