The newly elected government’s instant choice to follow confrontational tactics with Greece’s lenders and its loudly stated intention to stay away from any assistance programme resembling the arrangements of the two previous ones meant that any troika financing was put immediately on hold. This left Alexis Tsipras’s government with little choice but to start scraping the bottom of the funding barrel very early on.

Routine debt servicing and other obligations like the habitual rollover of T-Bills quickly became sources of drama, with the flames often fanned by statements of government and party members, including Tsipras himself, that Greece would pay pensions and salaries rather than the IMF if it was forced to make a choice.

Tsipras found himself in this exact position at the start of the summer, when Greece became the only developed country in arrears to the IMF after requesting to bundle all four June payments into one and finally missing that payment altogether at the end of the month.

To make ends meet, the Finance Ministry was looking for cash in every nook and cranny, collecting via repo operations, often with forceful persuasion, cash reserves from state owned enterprises, municipalities and other state bodies. Tsipras maxed out the cash management technique that his predecessor, Antonis Samaras, had used extensively when his own review was not going according to plan and programme disbursements were not forthcoming.

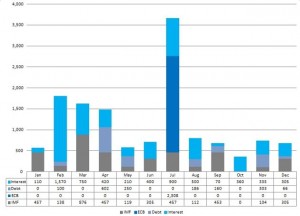

Financing via repos stood at 8.44 billion euros when Tsipras took power, peaking at 16.87 billion in July. By the end of June the deposits of the Hellenic Republic had dropped to a mere 77 million as more than 2.5 billion had been sapped in the previous twelve months by finance ministers Gikas Hardouvelis and his successor Yanis Varoufakis.

However, since the agreement of the July 12 summit there has been nothing to suggest a repeat of the tension of 2015. In fact, since Tsipras signed the agreement he has paid over 4 billion euros to the IMF and nobody seems to have noticed. Not only did he emerge victorious from the September election, his new government has managed to legislate all prior actions (in excess of 60) meet milestones and receive the relevant disbursements. Tsipras is fully compliant with the implementation of measures that this time last year he would not even touch with a barge pole.

Greece’s debt servicing profile in 2016 is quite benign. Privately held debt maturities come to just 1.7 billion euros, obligations to the IMF are under 4 billion, the ECB again poses a major hump in July with maturities of 2.3 billion euros while the overall interest bill is below 6 billion. In total, Greece needs 13.7 billion euros to meet all its debt obligations, which translates into 7.9 percent of GDP, almost half of what the IMF and the other institutions in the quartet consider a sustainable gross debt servicing burden.

What will put pressure on the cash front at the start of 2016 is the timetable of the third programme’s first review, which is expected to start in mid-January with the aim of it being concluded by the end of February and all actions and legislation being completed in time for the next disbursement to take place in early spring.

The first review is burdened with politically and socially sensitive measures, including an extensive pensions cost saving exercise that has to deliver complete savings of 1 percent of GDP. The government will also have to finalise the framework of the distressed debt market, including mortgages linked to primary residences. These are combined with the drawing up of a Medium Term Fiscal Strategy, which has historically been a toxic process as it often requires quantifying ahead of time austerity measures that will secure fiscal targets in subsequent years. This combination makes the conclusion of the review by the end of February quite ambitious even though no major deadline has been missed since July.

By February 1st, Greece will need to have paid the IMF marginally below 600 million euros. The first installment of around 450 million euros is due in mid-January. March has the largest IMF installment of the year at 876 million, which leads to a total figure of IMF obligations in the first quarter of close to 1.5 billion euros.

Next year’s interest bill is highest in February, standing at just under 1.6 billion euros. The total figure for the first two months of the year is approximately 1.7 billion euros. March interest obligations stand at 750 million, bringing the total quarterly interest bill close to 2.5 billion euros.

Privately held debt is not problematic in the first quarter, with only a bond issued in Yen maturing in February.

The state’s budget foresees a primary surplus of over 1 billion euros during the first quarter of 2016, with monthly surplus figures of 307, 758 and 30 million for each of the first three months. In fact, in January the entire budget is in a 197 million total surplus, turning into a cumulative deficit of 1.3 billion euros up to March.

In total, over the first quarter of the year Tsipras needs approximately 4 billion euros to meet all debt obligations, which factoring in the primary surplus leads to a net financing need of 3 billion. The most probable source of funding while the review is ongoing is the same repos exercise which, aside from the emergency nature so far, is seen favourably by the quartet. Greece’s lenders had previously suggested the formation of a framework of central cash management that will include all state owned and associated enterprises.

As much as the numbers do not pose an immediate problem for the government at the beginning of the New Year, it is highly probable that the first review will test Tsipras on the political front. He will have to convince an already tired and battered party and a parliamentary group with a very thin majority to agree to further reducing the income of pensioners after eleven previous rounds of cuts, agree further austerity measures in 2017 and possibly 2018, and place loans linked to primary residences as collateral under the control of distressed debt funds which only a year ago Tsipras himself was calling “vultures.”

What seems like a straightforward cash management exercise in the first quarter can quickly turn into a vicious cycle that will push any economic recovery further out of sight and inflict more damage on the already shaky relationship with creditors, before a repeat of last year’s crescendo when the ECB-held bonds placed a hard stop in front of Tsipras and led to his total submission.

Last year’s experience was not only dramatic for the prime minister and his party but also futile in the end. If anything, 2015 has made clear that Tsipras is a political survivor and there is little probability that he will endorse again an escalation of tension with the quartet.

The maneuvering will be challenging in a Greek political landscape that is allergic to consensus and where mistrust is abundant. It will be near impossible to part ways with the IMF and its hardnosed drive on conditionality, fiscal discipline and reforms of a specific ideological orientation that is not compatible with that of the left. Even the prospect of debt relief will not be put on the table before the successful completion of the first review and is expected to come in the form of maturity extensions, grace periods and keeping loan rates low, which is politically neutral for the creditors and does not give Tsipras significant capital given that his calls for a generous write-off are still fresh in the memory.

After a year during which Greece nearly saw it all, it could use some dull moments to get back on its feet. In the framework of the MoUs, the task of demanding fiscal targets and further austerity is far from over and it will once again set the tone for the New Year in the ongoing cycle that has defined the crisis since 2010.

The distance between virtuous and vicious is still just a wrong turn away.