On the same day that the Bank of England opted not to pump more money into Britain’s stagnant economy, the Bank of Japan unleashed the third ‘arrow’ in its recovery package. This arrow aims to aggressively target higher inflation by pumping money into the economy through asset purchasing. It is aiming to do this by doubling its government bond holding over the next two years to help achieve inflation of 2%. This supplements a massive supply-side push and some economic ‘restructuring’.

At home, the chancellor, George Osborne, tweaked the Bank of England’s remit to give it clearer scope to overlook short term upward pressures on inflation. But in the phoney war that is raging prior to Mark Carney’s arrival, the central bank said it would not add to its QE spend this month. The government has purchased £375bn government bonds between March 2009 and October 2012, something of a global record.

Britain aggressive monetary easing started earlier than other economies. Gordon Brown started in 2009 and Osborne continued the jamboree until October 2012. The important questions are:

1. How good was our timing, will it prove to be beneficial to be the trail blazers in what may become a global reflationary cycle? (The US, Japan and EU are all setting off down this road)

2. Will our stubbornly high inflation put us at a disadvantage in this cycle – along with emerging economies like Brazil, India and Russia who still have structurally high inflation?

3. How will low inflation economies like Japan fare (where deflation has been strangling the economy for two decades)?

4. What will Mark Carney have up his sleeve?

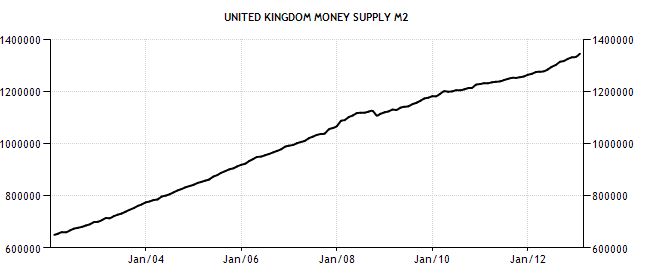

Commentators are expecting Mark Carney, the current governor of the Bank of Canada, to trigger a broad review of the central bank’s policy framework. But he may have his work cut out as the charts below show how little effect monetary policy seems to have on the actual money in circulation!

Despite Gordon and George’s best efforts the UK’s M2 (cash in circulation and short term deposits) number has grown at a consistent rate over the last 10 years, excepting the downward blip in the 2008 credit crisis. Where has they have “spent” £375bn gone?

It seems to me that the UK QE has merely allowed the banks to off load UK government debt and replace this with other government debt, helping to keep bond prices high but having no impact on the real economy, other than to keep interest rates artificially low. Maybe the Japanese version of QE combined with a massive supply side push will have a more profound effect.

What surprises me is that more governments haven’t looked to the demand side (lower taxes on spending and income) to drive growth and inflation. Perhaps the best and boldest policy decision since 2007 in the UK was Brown’s temporary cut in VAT (sales tax) in 2009 this got the money supply moving again and should probably been kept in place. The £15bn annual cost of this tax cut cost could have been covered in lower welfare payments and deeper government spending cuts.

Be the first to comment on "The Ying and Yang of Economic Policy"